In my research of black minstrel troupes, it has become obvious that American pop culture is infused with references to minstrelsy. Although this influence becomes obvious when it is pointed out, I would like to propose a claim that might not be as readily accepted. Not only is minstrelsy heavily involved in American media, the influence of the minstrel show is a pillar of American art and media. In other words, elements of minstrelsy actually contribute to what it means for a piece of media to be “American”.

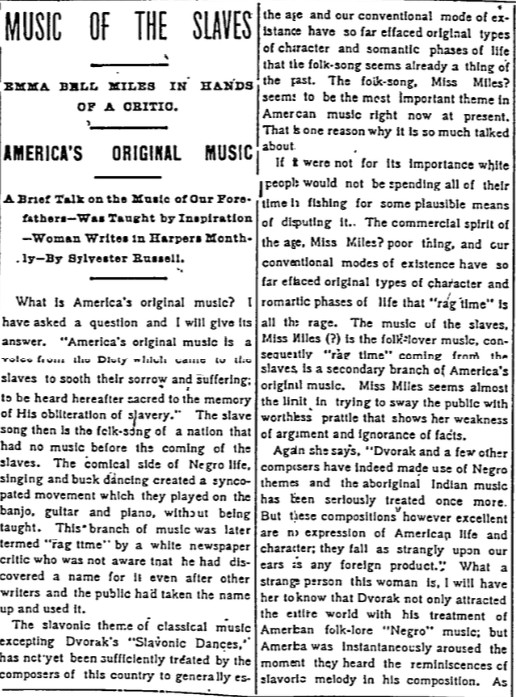

The American-ness of the minstrel show and minstrel influences can be seen in the perception of the minstrel show from audiences abroad. In my own mapping of black minstrel shows, I noticed very quickly that these shows were mostly plotted in the U.S. Perhaps this article posted in the Freeman newspaper might give more insight into why that is.

This article posted in the the Freeman in Indianapolis, Indiana on February 8, 1902 titled “The Negro Performer Abroad” explains how the minstrel show was not well received abroad. The article writes: “The English and Australians, by the way, are very austere and reserved as regards the manner of entertainment of histrons, therefore that which we here consider clever, they, over there regard indifferent and treat with almost heartless disdain. Little wonder then that early Negro minstrels met a cold reception and proved a ‘frost’”. 1

This indifferent reception shows us the extent to which American media and humor differentiated from that of Europeans and Australians. In other words, this humor is strictly American.

We can see this inclusion of minstrel influences as well in other forms of media such as animation in more sinister, more blatant ways. For example, in Ammond’s book “Birth of an industry: blackface minstrelsy and the rise of American animation” he argues that certain characters, such as Mickey Mouse, carried “all (or many) of the markers of minstrelsy while rarely referring directly to the tradition itself”. 2 For example, in this video of the first Disney animation “Steamboat Willie”, we see that Mickey is whistling a minstrel tune and also wears the distinctive white gloves worn by minstrel performers.

http://https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iep9EJ9H1aU&ab_channel=amandawelling

These examples of the influence of minstrelsy on American media show how truly interlaced it is with American identity. The inclusion of minstrelsy can really be seen as a staple of American identity. Although this fact is incredibly troubling, by understanding its implications, we can begin to uncover and become critical about the nature of American identity itself.