While looking through the Sheet Music Consortium, it occurred to me to look into songs I had some base familiarity with. Go Down, Moses is a very popular spiritual which originated from enslaved African Americans on plantations. The song itself refers to Moses and the Hebrew people. In said story, the Hebrews are held captive by the Pharaoh. God tells Moses through the story of the burning bush to free his people from the Egyptian tyrant. Through sending plagues, flocks of locus, making the red sea red with blood and more catastrophes, the Pharaoh agrees to let the Hebrew people go. To the enslaved African Americans working their lives away, this spiritual was the promise of emancipation.

familiarity with. Go Down, Moses is a very popular spiritual which originated from enslaved African Americans on plantations. The song itself refers to Moses and the Hebrew people. In said story, the Hebrews are held captive by the Pharaoh. God tells Moses through the story of the burning bush to free his people from the Egyptian tyrant. Through sending plagues, flocks of locus, making the red sea red with blood and more catastrophes, the Pharaoh agrees to let the Hebrew people go. To the enslaved African Americans working their lives away, this spiritual was the promise of emancipation.

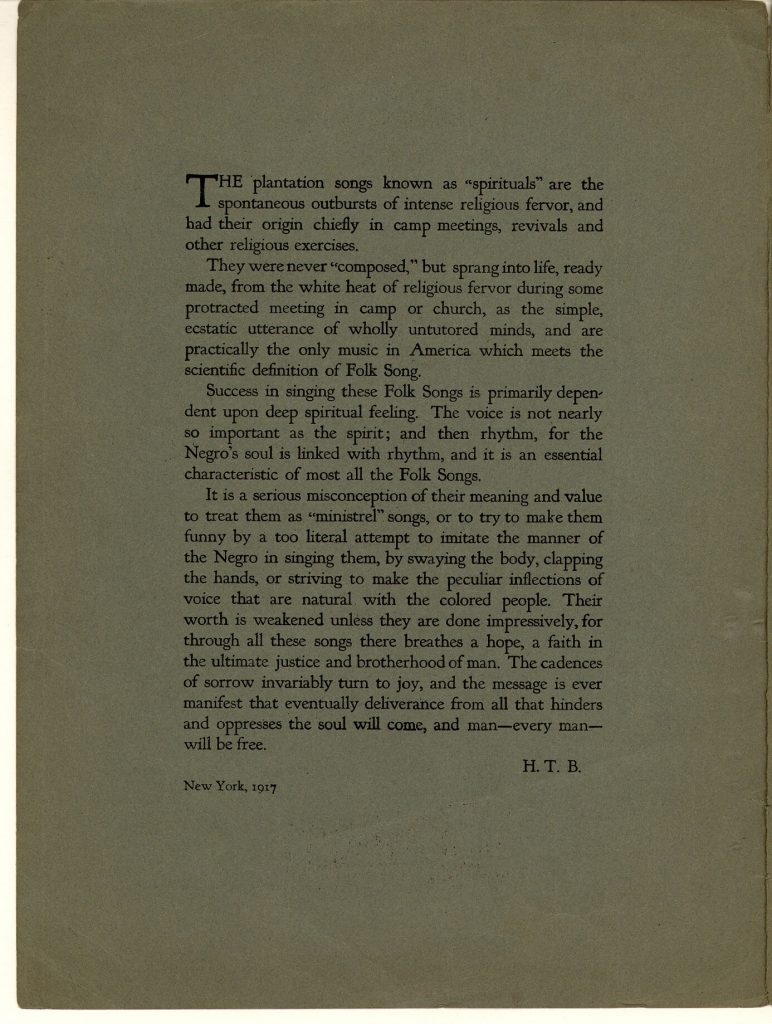

Included above are the notes in the front cover from H.T. Bureigh on the difference between spiritual and minstrel, how to perform this piece, and what this piece and these words mean. H.T. Burleigh writes about how to perform this piece, and what it means for African Americans. To begin with, a spiritual is so much more than just a song. It represents a message of freedom and hope to for the performer and their audience. The goal of a spiritual is to stir the people and help them think in a different way, or further affirm their beliefs. In order to sing correctly, you have to have soul, more than correctness of pitches. Burleigh invites the singer to feel the words, so that every man will be free. Minstrelsy was a crude misrepresentation of black people and their culture. Spirituals deserve respect and recognition as pillars of American music. Few were better at arranging these soulful spirituals as H.T. Burleigh.

On the topic of H.T. Burleigh, in Music 345, we have studied Burleigh, so that name likely rings a bell. H.T. Burleigh was one of the first prominent black composers. In his life, Burleigh had a small singing career and arranged art song but focused mostly on arranging and composing spirituals. His works are still performed to this day, about a hundred years later. The song itself has stood the test of time, being one of the most popular spirituals ever. But just as the song stands the test of time, so does this story. His words, in the front cover of Go Down, Moses invoke the message of the spiritual. This, of course, is something we continue to strive for today as a society. And yet, people still need to hear these words in order to believe them, and to understand that all people must be free.

Go Down, Moses; Let My People Go!, Burleigh, H. T. (Harry Thacker), 1917, Accessed 10/20/2022.