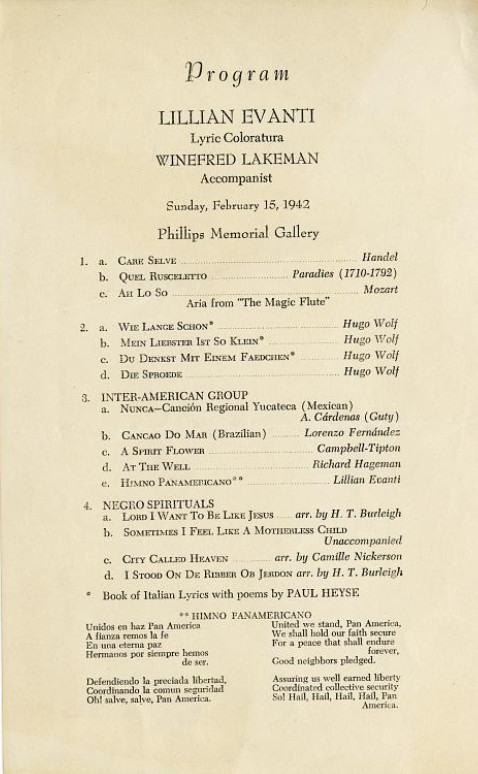

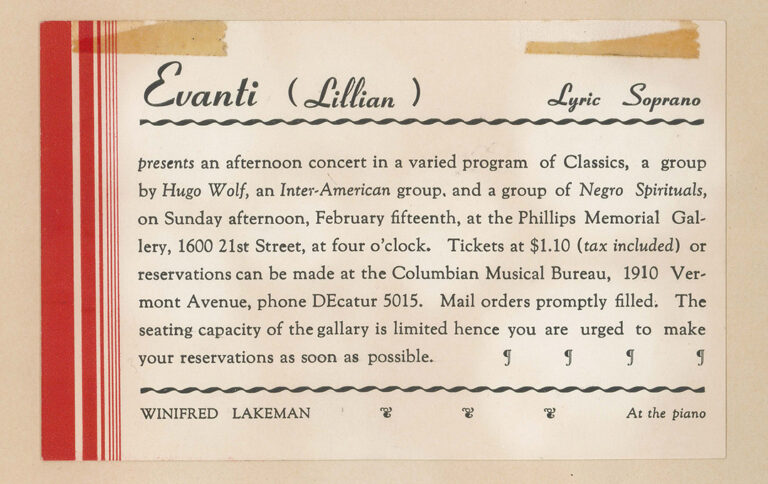

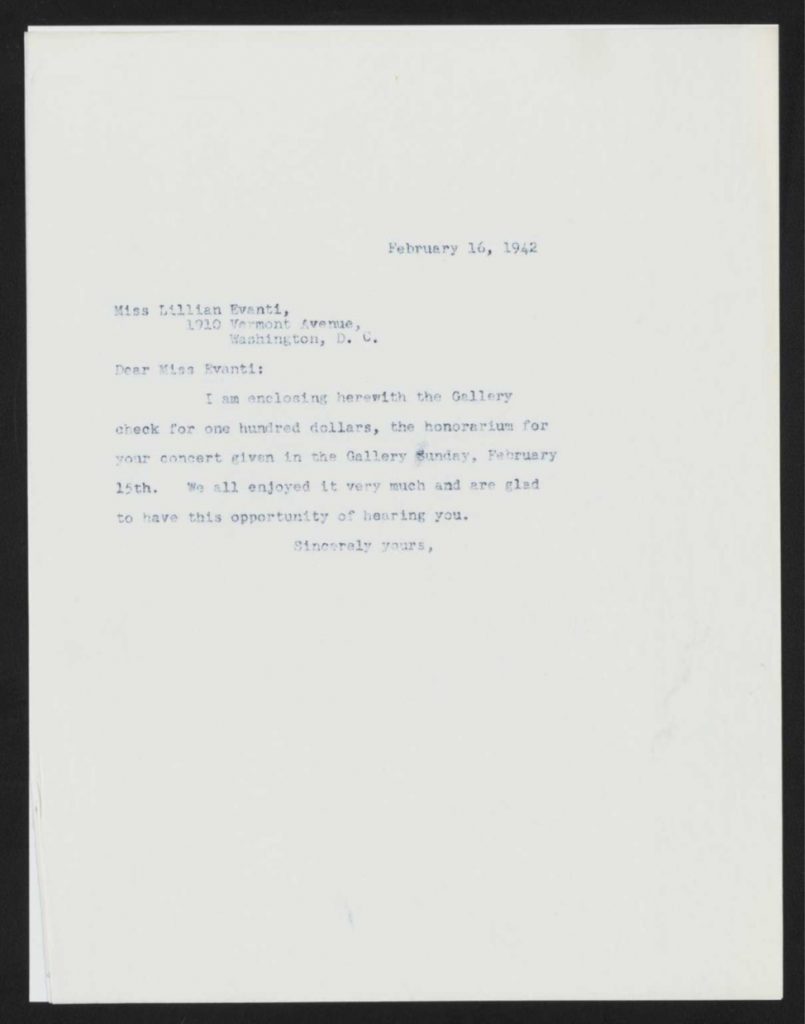

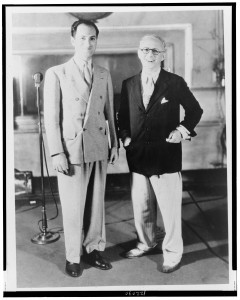

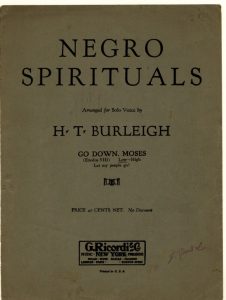

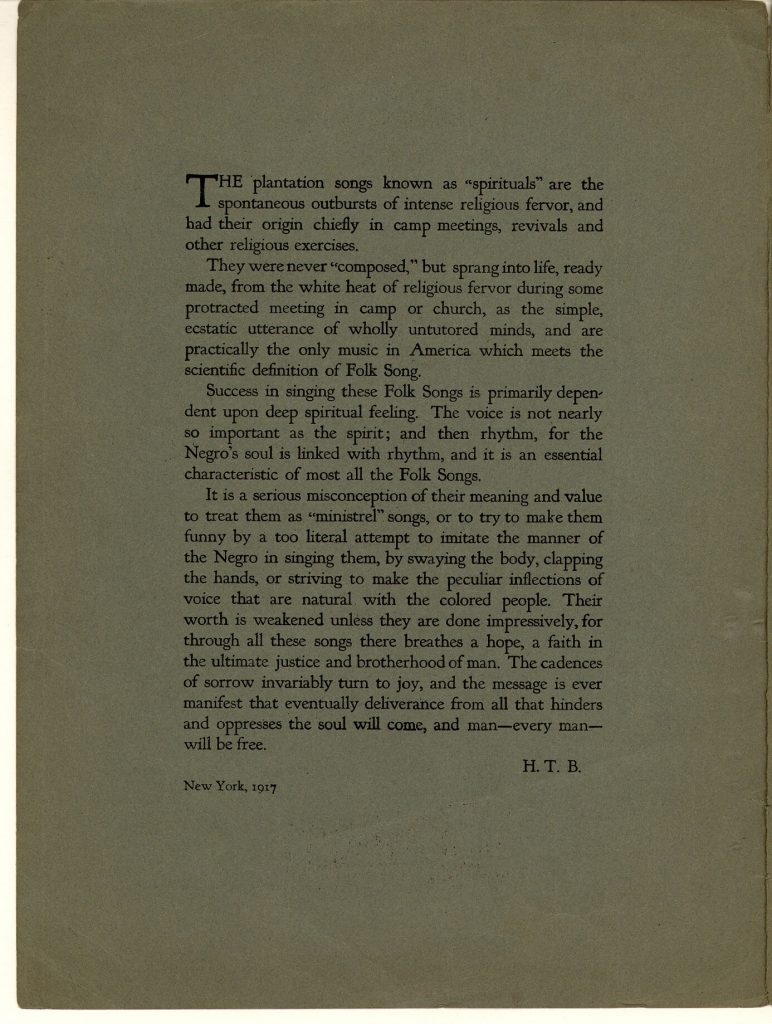

It feels fitting to write a blogpost on ‘American Music’ and who owns it after studying  this question for an entire semester. According to The Chicago Defender, it is the song of the enslaved people that truly inspired (or birthed, in their own words) American music. The beginning of this article describes the argument that white people are the source of American music rather than that of bipoc and enslaved people. The Chicago Defender wastes no time in correcting this absurd sentiment. The author goes on to write about bipoc composers, writers and musicians. The author similarly takes a world view that all races are musical, and the truth of their being is expressed through their music. This I agree with, music expresses more than any other medium does. This expression, according to the author is one of divinity, and is an extension of God’s Way. While I don’t consider myself religious (a source of implicit bias I have) the sentiment of the author makes sense.

this question for an entire semester. According to The Chicago Defender, it is the song of the enslaved people that truly inspired (or birthed, in their own words) American music. The beginning of this article describes the argument that white people are the source of American music rather than that of bipoc and enslaved people. The Chicago Defender wastes no time in correcting this absurd sentiment. The author goes on to write about bipoc composers, writers and musicians. The author similarly takes a world view that all races are musical, and the truth of their being is expressed through their music. This I agree with, music expresses more than any other medium does. This expression, according to the author is one of divinity, and is an extension of God’s Way. While I don’t consider myself religious (a source of implicit bias I have) the sentiment of the author makes sense.

While we may never have a full encapsulation of what ‘American music’ truly is, it most certainly includes those of bipoc people.

Work Cited