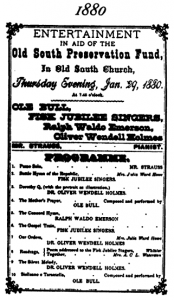

Nowadays, and throughout much of history, highbrow classical music has typically been reserved for an estranged elite – an exclusive club that everyone could hypothetically join, but hardly anyone ever does. (Other than you of course, dearest Reader, who are most exceptional) The reason for this hierarchical cultural separation, both in music and other areas, is manifold, ranging from snarky snobbery to preposterous pretentiousness. However, this need not, and – perhaps more importantly – has not, always been the case. As noted in the March of Time database’s newsreel, Upbeat in Music1,

America’s serious composers are winning recognition from an ever-widening public, through performances by symphonic conductors like the New York Philharmonic’s Rodzinski…. The nation’s crowded concert halls testify to the new and growing enthusiasm of hundreds of thousands of everyday citizens for good music. The classics they have heard on records or on the radio, the moving artistry and musicianship of singers, who today are being heard by the whole country. And, like Marian Anderson, are singing songs which are part of the native music of America.

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(90)/discogs-images/R-6472881-1420086029-1218.jpeg.jpg)

The 3 Tenors – one of the strongest examples of classical musicians who became outrageously popular beyond the traditional classical sphere

As Karene Grad explains2, the divide between classical and popular music was much smaller in post-WWII America. She even goes so far as to say that “the years following World War II saw the popularization of high culture in America.” The arts at that time were a fundamental piece of the struggle to create an exceptional American identity. Unfortunately, arts are no longer such a valued piece of American culture and identity today. It seems as though new cuts are made in arts programs across the country every day, and that it is hopeless to try and fight against America’s modern STEM-centric worldview. However, we can take solace in the fact that there was a time when arts did play a central part in American culture, and perhaps, if we work at it hard enough, such a time might come again.

1 Upbeat in Music. Produced by Home Box Office. http://search.alexanderstreet.com/view/work/bibliographic_entity%7Cvideo_work%7C1792615. Accessed November 16, 2017.

2 Grad, Karene, Agnew, Jean-Christophe, and Cott, Nancy F. When High Culture Became Popular Culture: Classical Music in Postwar America, 1945–1965, 2006, ProQuest Dissertations and Theses. https://search.proquest.com/docview/304983472?accountid=351. Accessed November 16, 2017.