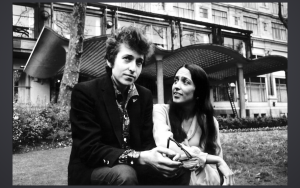

What is folk music? Is folk defined by the musical intentions of the musicians themselves, its political and social implications, or its consumption? For artists like Woody Guthrie, Bob Dylan, Pete Seeger and so many others, folk was a political endeavor. Another notable artist was Joan Baez, who was known for her captivating soprano voice and her impressive guitar skills. However, Baez was more than just a folk singer with talent; she was an adamant peace and civil rights activist and much of her music reflected her political ideals. Baez was considered to be a part of the folk revival movement. She performed at the Newport Folk Festival in 1959, launching a very successful career.

According to Bruce Jackson in his The Folksong Revival he claims that the folk revival movement was just a fad. This blog is an attempt to reflect on Jackson’s opinion by providing reasons in which I think the folk music revival was not just a fad, but it was a necessary movement to propel the ideas of activists a that time.

“I think the revival can be fairly categorized as romantic, naive, nostalgic and idealistic…much of the revival was a fad or fashion” ~Bruce Jackson

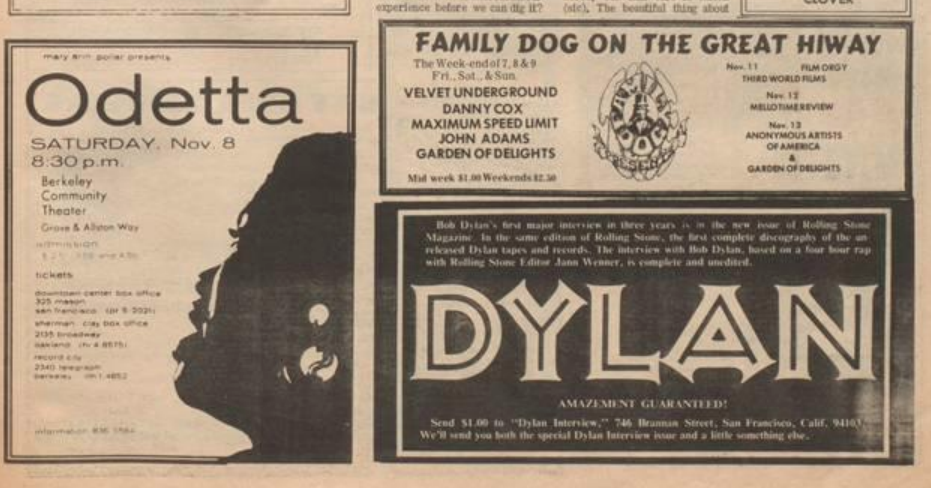

So why folk revival? Today, many of us view folk as a simple song associated with possibly nostalgia, home, or sentimental feelings. Most people envision folk as a smaller communal setting, but the Newport Folk Festival of 1959 suggests otherwise. Newport was one of the larger gatherings to celebrate folk music and it’s artists. One reason the folk revival may have gained traction was because of the desire people had to reconnect with their American roots. What’s a better way to do that than through folk music? But, folk music has more value than just for the enjoyment of old times sake.

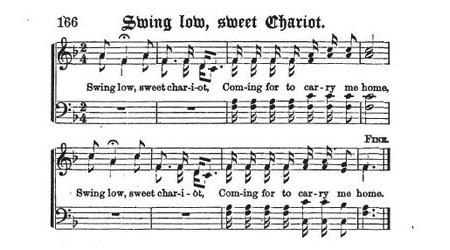

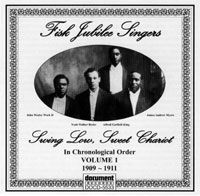

Artists like Baez used their skills and political views to highlight the flaws of the cultural and political environment. Not only did Baez seek to share her ideas through folk inspired music, she gained traction with these ideas and helped spread her political views. Because Baez and many artists infused folk music with messages of peace and equality, it is clear that folk had an extremely important purpose in our social and political history. Protest music was music that would reject certain ideals of actions. For example, “We Shall Overcome” became the anthem to the civil rights movement. In Joan’s rendition, she combines folk and jazz elements, connecting this song to different styles of music and boring from other traditions therefore catering to many people.

In the Oct 4, 1971 issue of the Chicago Daily Defender, the article “Joan Baez has a Problem” was written criticizing her disrespect for the American Flag.

Article criticizing Baez’s political opinions regarding the American flag- “Joan Baez has a Problem” October 4, 1971 in the Chicago Defender

“This piece of cloth has become an obscenity. We know how to protect and reverence that Flag. But we don’t know how to protect human life.” ~ Joan Baez

The Folk Revival movement was not just a fad. It was a means to react to and process the political and social injustices that the world was faced with in the 60s and even today, proving folk musics’ relevance and importance not only then, but also now. In a time of racial and international tension, it is not surprising that folk music became popular. It provided a sense of comfort and connection to one another when the country seemed in all other ways divided. Folk advocated for all people of all backgrounds, races and statuses.

Work Cited

Bob Dylan Singer Songwriter with Joan Baez American Folk Singer. 27 Apr. 1965.

“Joan Baez has a Problem.” 1971.Chicago Daily Defender (Daily Edition) (1960-1973), Oct 04, 4. https://search.proquest.com/docview/494322582?accountid=351.

Matthew, Adam. “Folk Protest.” Popular Culture in Britain and America, 1950-1975, 2017.

Rosenberg, Neil V. “The Folk Song Revival.” Transforming Tradition: Folk Music Revivals Examined, University of Illinois Press, 1993, pp. 73–79.

Women Peace Protestors of Northern Ireland on a March in London. 29 Nov. 1976.