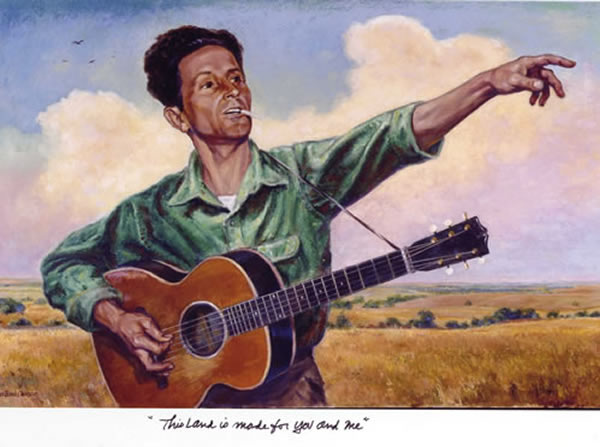

Last Fourth of July weekend, I attended church with some family friends. After the service everyone gathered in back to sing some patriotic songs together. One of those songs, I remember, was “This Land Is Your Land” by Woody Guthrie. I didn’t find anything curious about it at the time–the lyrics were fitting for the occasion. But then I learned when the song was written and what the original lyrics were. (Spoiler alert: We were not singing all the original lyrics.)

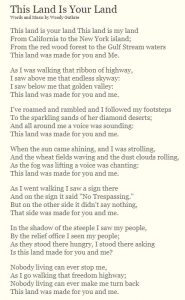

Post-1944 lyrics taken from the official website of Woody Guthrie

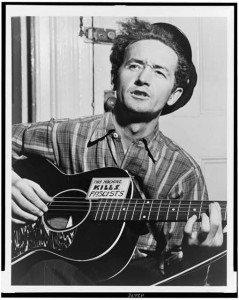

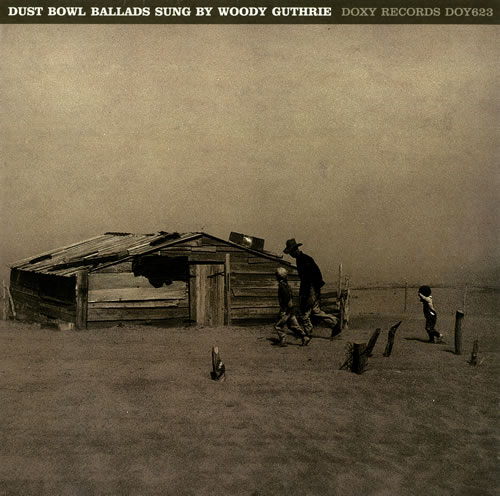

During the Great Depression, Irving Berlin’s “God Bless America” became an optimistic anthem for the hard times. In 1940, Woody Guthrie wrote “God Blessed America for Me”, with the phrase repeated at the end of each verse, in response to Berlin’s hit song.1 The lyrics were meant to capture a more accurate image of the United States, still celebrating the land but “without glossing over its imperfections or pretending that all in America were blessed equally.”2 The last couple verses were especially overt in their political protest, and–what I find most fascinating–the song ended on a question: “I stood there wondering, if God blessed America for me.”3

When Woody Guthrie changed the title to “This Land Is Your Land” in 1944, he altered the repeated lyric to “This land was made for you and me.”4 Thus, his message became a lot more inclusive. This turned the ending question into “I stood there asking, Is this land made for you and me?” However, in his 1947 recording, he left out the two protest verses but added another verse (“Nobody living can ever stop me…”). While previous versions have been very difficult to find, this is the version that has become most well-known.5

Despite the changes it has undergone, the lyrics of “This Land Is Your Land” still promote inclusivity–a land for you and me, where no one should be left out. The song was even adopted as a campaign song for the NAACP in the 1950s.6 Because Guthrie supported the Civil Rights Movement, I’m sure he would be proud to know his words were used in the fight for equal rights. On the other hand, his words have also been adopted by military bands, big corporations, and presidential campaigns for the purpose of eliciting patriotic sentiments.7 (I even sang it in a church around Independence Day.)

It’s incredible how one song, originally intended to question the ‘blessed’ nature of this country, has become known today as an optimistic, patriotic tune, alongside “God Bless America”. I’m not saying this is a good or bad thing, but I do believe it is important to keep in mind what this song originally stood for and what it asks: was this land blessed for you and me?

1 “This Land is Your Land.” Library of Congress. https://www.loc.gov/item/ihas.200000022/.