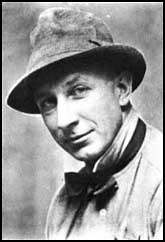

This week we toured the St. Olaf Flaten Art Museum and studied several objects, including this painting, “Head of Boxer” by George Wesley Bellows.

George Wesley Bellows (1882-1925) was an American realist painter, known for his depictions of urban life in New York City. He was an artist from the Ashcan school of art, that were a group of realist painters that wanted to challenge and be set a part from American impressionists.

Although Ashcan artists advocated for modern actualities, they were not so radical that they used their artwork for social criticism or reform. They identified with the vitality of the lower classes and illustrated the dismal aspects of urban existence. However, they themselves led middle-class lives and were influenced by New York’s restaurants, bars, theater and vaudeville.1

Relating to other themes in our class, George Bellows was immersed in New York’s vaudeville scene around the same time of Charles Harris’ “After the Ball”, Howard and Emerson’s “Hello My Baby”, and Irving Berlin’s “Alexander’s Ragtime Band.”

“The Ashcan artists selectively documented an unsettling, transitional time in American culture that was marked by confidence and doubt, excitement and trepidation. Ignoring or registering only gently harsh new realities such as the problems of immigration and urban poverty, they shone a positive light on their era.”

— The Metropolitan Museum of Art

In this painting, perhaps the rough brush strokes represent the difficulties the lower classes faced in society? Perhaps the mix of light and shadow on the boxer’s forehead show the transitional time in American culture? And perhaps the sad expression of the boxer represents the doubt and trepidation of the lower classes who struggle with problems of immigration and urban poverty. George Bellows painted the realities of the lower classes he saw around him in New York City.

1 Weinberg, H. Barbara. “The Ashcan School.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art. 2000. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/ashc/hd_ashc.htm