Hollywood cinemas in mid-20th century would use blues songs as a means to articulate racial instability in the characterization of women who represented problems in terms of their sexuality, their morality, and their (lower) class status.

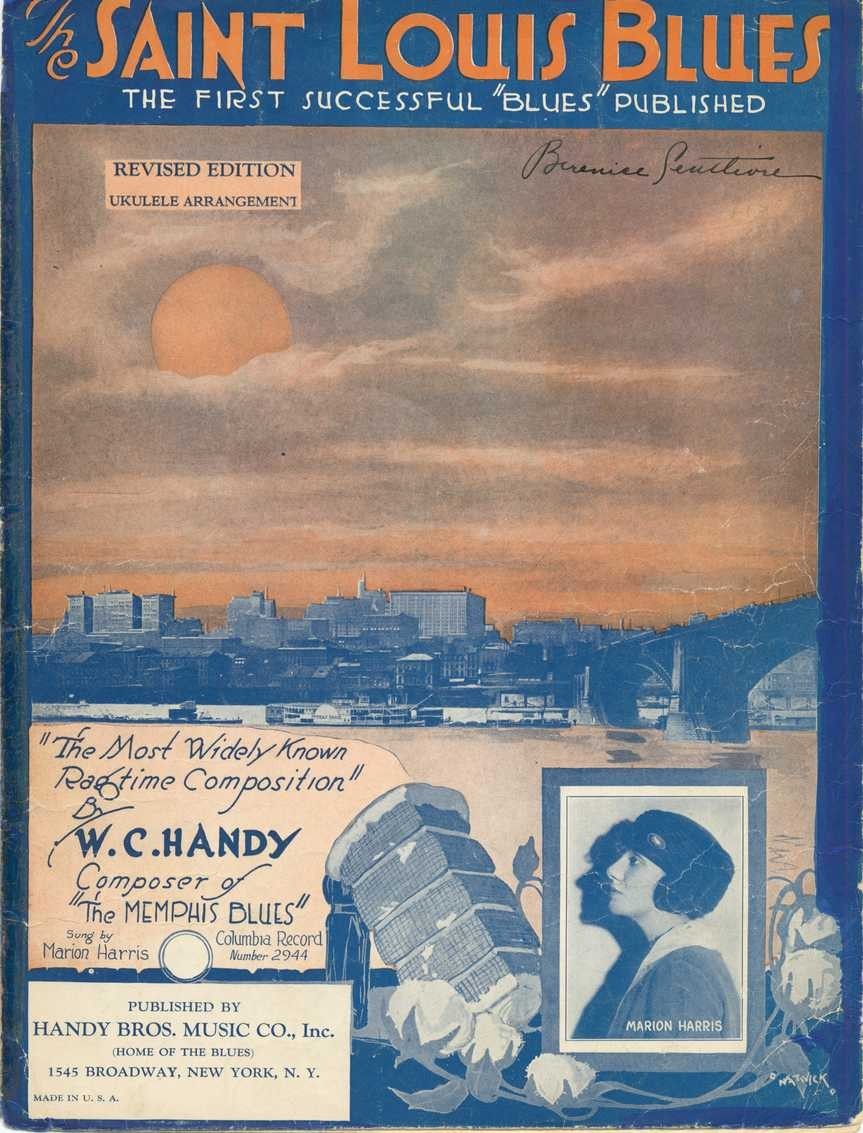

The song St.Louis Blues would be an example.

Composed by W. C. Handy in 1914, St. Louis Blues was first featured in black vaudeville circa 1916 by Charles Anderson. On the basis of the song’s popularity, Handy has been called “The Father of the Blues”.

The song begins with a woman’s lament for the end of the day: “I hate to see de evenin’ sun go down.” Her man has left her for another woman who had “store-bought hair” and became a temptation too great for him to ignore. Composed in G major, St. Louis Blues is a 12-bar blues that combine ragtime syncopation with “a real melody in the spiritual tradition”. Handy also addressed that features from tango music was also figured in the introduction as well as the middle strain. In the famous Marion Harris version, the tango motif was played by violins, with bassoon’s humorous staccato, creating the image of a lovesick woman, full of lovelorn sadness but still has the longing for life.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=o4Qccz2qsHY

Handy writes in his autobiography:

However, did the Hollywood film production interpret the music as W.C. Handy’s interpretation? My answer would be NO- the hardness in life and love relationship was mostly lost. According to Peter Stanfield, Stella Dallas (1937) provided a good example of the complex ideological work that was often performed by blues music. Stella “decay” from a “mother” to a “sexualized” when she laying on the sofa with a sexy pose and playing St. Louis Blues on her phonograph (after seeing all these, Stella’s daughter decided to leave Stella forever). I think it is clear that the symbolic power of St. Louis Blues was shown here, by the “transgressive” female sexuality, the “blackening” of white identity, and “urban primitivism.”

http://youtu.be/7sJun3eM8UY?list=PLaTUqD7vwzLXjcM8djw38nSPvnfkTcAS3

I personally think it is not an occasion that the White society perceived Blues as “primitive” but “sexy” in early 20th century. Sociologist Gramsci’s idea of “culture hegemony” had to play in somewhere. White society would just love to take anything they want to take from black music- they redefined it and distorted it in order to adjust the entertainment of white people, without any further understanding of what the music actually talked about; Yet at the same time, African American musicians seemed already “accepted” the twisted impression in White society since they had to sale their music to white music dealers and singers, in order to make a living.

Sources:

Stanfield, Peter. 2002. “An Excursion into the Lower Depths: Hollywood, Urban Primitivism, and St. Louis Blues, 1929-1937”. Cinema Journal. 41, no. 2. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1225853

. “Handy, W.C..” Grove Music Online. Oxford Music Online. Oxford University Press, accessed March 4, 2015, http://www.oxfordmusiconline.com/subscriber/article/grove/music/12322.

Handy, W. C. St. Louis blues. New York: Handy Bros. Music Co., Inc., 1914.http://purl.dlib.indiana.edu/iudl/lilly/devincent/LL-SDV-09808