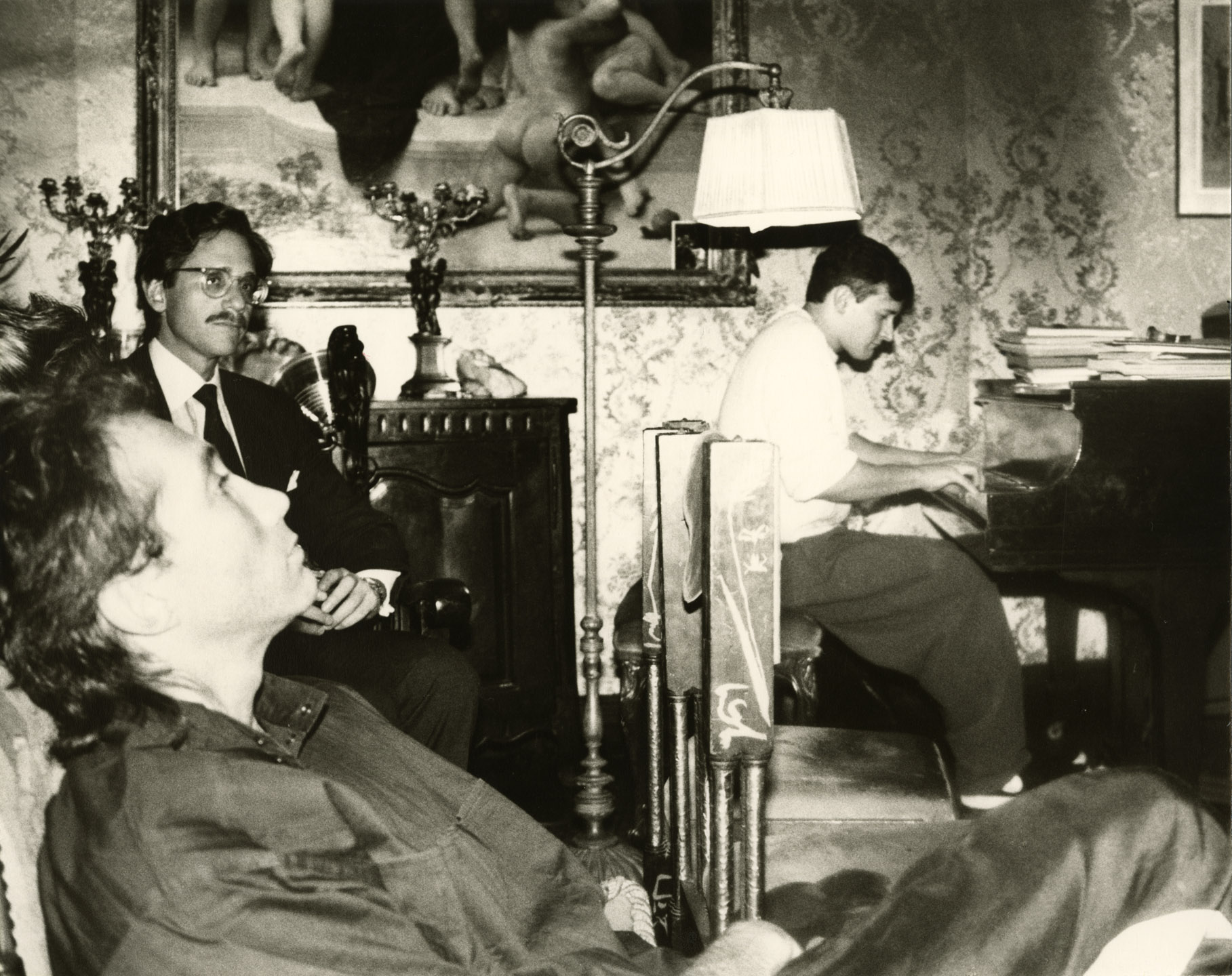

Andy Warhol

Christopher O’Riley and Two Unidentified men- Now in St.Olaf Art Collection

gelatin silver print on paper

8 in. x 10 in. (20.32 cm x 25.4 cm)

2008.272

Gift of © The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.

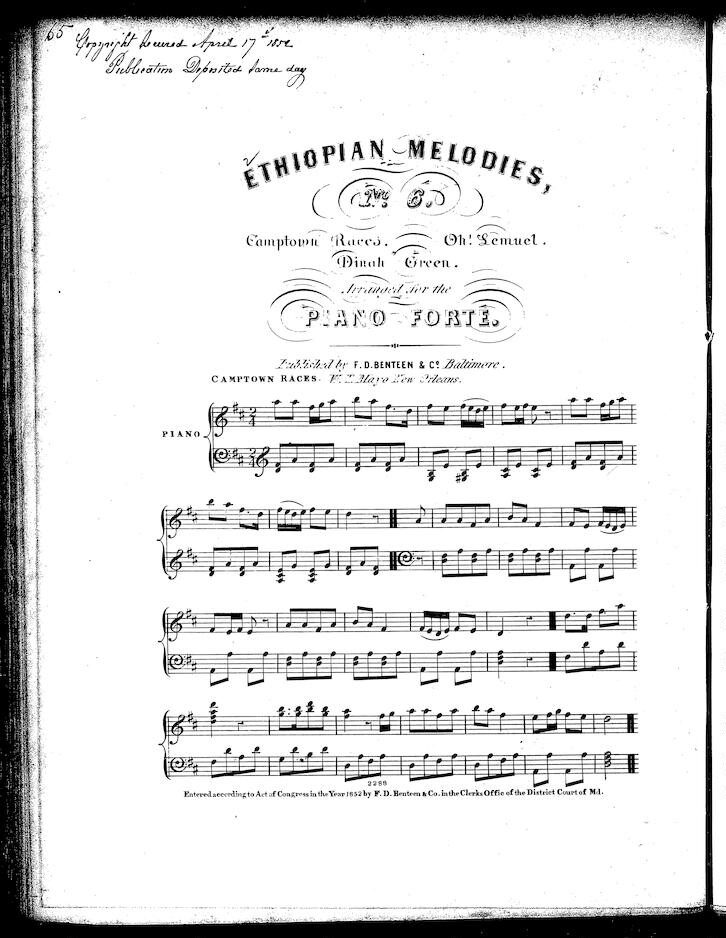

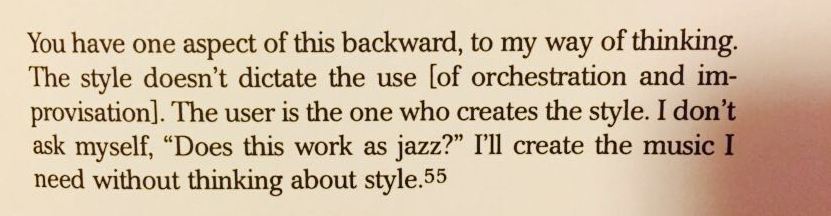

This Photo that was showed in the collection is a photo taken by Andy Warhol, probably in early 1980s. It captured the moment when the young pianist Christopher O’riley played music for Andy Warhol and three other audiences. It would be risky to guess what O’riley was playing, but from where I stand, probably jazz. As what O’riley said when he thought of the good memory with Andy Warhol:

Interview: http://www.interviewmagazine.com/music/christopher-o-riley-velvet-underground/#_

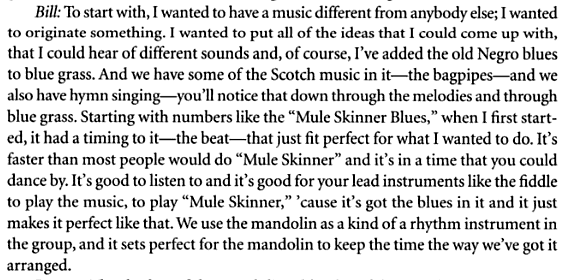

They were good friends. As what O’riley remembered, the man who introduced he to Andy Warhol was Stuart Pivar. Pivar went to a lot of auctions together with Warhol and they co-founded the New York Academy of Art. One of O’riley’s friends took him to Pivar’s house- and that was how he met Andy Warhol. O’riley often played music for Andy Warhol, Ford models, art collectors, and experts in the apartment. Taking these into account, through careful observation viewers might find out that all human figures in the photo can possibly be upper-middle class elite men, sitting in the delicate room with the art nouveau style lamp and Bouguereau-like academic painting on the wall.

Even more interesting, Christopher O’riley started to host the National Public Radio program From the Top in a way that Andy Warhol suggested- do absolute O’riley’s music. In the show, He started to do groundbreaking transcriptions of the rock band Radiohead with his own interpretations of classical music and new repertoires, and this made him famous for his piano arrangement of rock music.

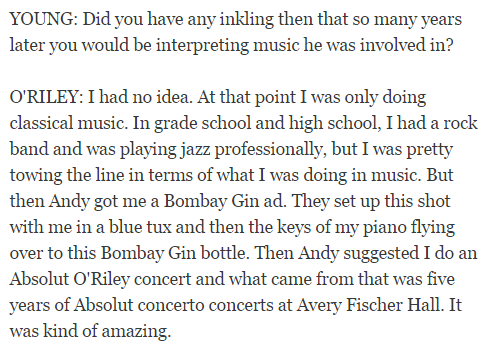

As what he said in the interview:

“Dealing with music as a contemporary form and not something in a museum definitely led to my confidence to do my own things.”

Works Cited:

http://www.interviewmagazine.com/music/christopher-o-riley-velvet-underground/#_

Ewing, Tom, ed. The Bill Monroe Reader. University of Illinois Press, 2000.

Ewing, Tom, ed. The Bill Monroe Reader. University of Illinois Press, 2000. Keil, Charles. “Who Needs” The Folk”?.” Journal of the Folklore Institute(1978): 263-265.

Keil, Charles. “Who Needs” The Folk”?.” Journal of the Folklore Institute(1978): 263-265.