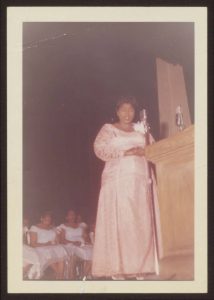

If I’ve learned anything from the past few years of music history courses, it’s that music of all kinds has a complicated and intertwining history. Music doesn’t exist in a bubble, and often, the development of assumed distinct musical genres depended on contemporaneous cultural and musical influences. Rock and Roll is no exception to this statement. In fact, this 1969 article from the Chicago Defender argues that Rock and Roll owes many of its musical traits from the Gospel genre. Despite the apparent disparity between Gospel and Rock and Roll, Earl Calloway, the article’s author, argues that the chord progressions and “uninhibited style of singing” found in rock music are derived directly from gospel music sung in church. Mahalia Jackson, who Calloway mentions later in the article as one of the first Gospel singers to break into pop culture, is a perfect example of this hybridity. In fact, Jackson was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1997. Rock stars like Little Richard count her among their major influences and the syncopation that can be heard in songs like ““Move On Up a Little Higher,” and “He’s Got the Whole World in His Hands” served not only to popularize Gospel music (“He’s Got the Whole World in His Hands” reached the top 100 on the Pop charts), but as a foundation for later rock idioms. Take a listen to “Move on Up a Little Higher” and see if you can hear some Rock and Roll:

In listening to Jackson’s recording, however, it is also evident that the Gospel style she used didn’t develop in a vacuum. Thomas Dorsey, who some (like Richard Crawford in his book American Musical Life) identify as one of the founding forces in Gospel Music worked and toured with Mahalia Jackson to develop the Gospel Sound. What is impossible to ignore in these recordings is the similarity it has to earlier Blues traditions. Mahalia Jackson drew inspiration for her vocal technique from the likes of Ma Rainey and Bessie Smith. However, instead of traditional Blues topics for her songs, she sang sacred music. Mahalia Jackson demonstrates the increasing readiness of popular music in the 20th century to change and rely on the music that came before it while influencing the music that would come later. While Gospel certainly was and is a distinct tradition from Blues or Rock and Roll, the interaction between these genres cannot be denied.

While the article from the Chicago Defender and the photograph of Jackson now housed in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame demonstrate the complicated history of musical development and transmission, they fail to acknowledge another fundamental part of music: politics. Musicologists and musicians alike, myself included, sometimes like to think of music as apolitical. I find it all too easy to hide behind theoretical analysis and stark historical facts when considering the development of musical genres. To do so, however, is to help erase and negate narratives of privilege and oppression that infected all aspects of history, including our beloved music. Mahalia Jackson’s recordings and life as a whole serve as an example of how music works as part of an inescapable political system. Her music was an influential part of the Civil Rights movement. She worked with Martin Luther King Jr. throughout the Civil Rights campaign and even sang at the 1963 March on Washington. By the very value of her identity (being a black woman in the 1960s), she and her music had no choice but to be deeply embedded in the social struggles of the 1960s. Click the play icon below to listen to this interview where Jackson speaks about her struggle to maintain Dr. King’s policy of nonviolence when confronted with egregious acts of racism throughout her career and in her personal life.

As interesting as Mahalia Jackson’s involvement with the developing hybridity of popular music in the 1960s is, equally important are her efforts to mobilize music as a political tool.

, et al. “Jackson, Mahalia.” Grove Music Online. Oxford Music Online. Oxford University Press, accessed October 17, 2017, http://www.oxfordmusiconline.com/subscriber/article/grove/music/A2249902.

Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. “Mahalia Jackson.” Rock & Roll Hall of Fame. Accessed October 17, 2017. https://www.rockhall.com/inductees/mahalia-jackson.

The Story: A project by American Public Media

Archives

Pop Culture in Britain and America: 1950-1975