When Charlie Parker died on March 12, 1955, he left a massive void in the world of jazz. While tragic, it was inevitable: a long battle with heroin addiction had threatened his life in the past. Though he didn’t invent the genre, he was widely considered to be one of the “fathers of bebop” who had galvanized the transformation of Duke Ellington’s “specialized jungle rhythm” into the virtuosic, intellectual, and cutthroat style of post-war jazz.[1]

Less than a month after his death, the national edition of the Chicago Defender suggested that Parker’s passing also signaled the end of bebop. The article claimed that without ‘Yardbird’ Parker “time and wear may render [bebop] worthless commercially.”[1]

While this concern may seem legitimate in the face of tremendous loss, modern hindsight rejects the notion that death can halt the development of musical style, particularly when that development stems from a genius. Parker, aside from being responsible for the partial transformation of musical sound, was also responsible for the transformation of musical thought. He revolutionized the way jazz musicians though about harmonic approaches to improvisation. He also drastically increased the use of contrafact composition (composing over existing harmonic material), expanding the framework in which jazz musicians could operate and providing a model for how they could develop their musical chops.

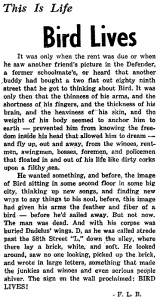

For all of the praise that the Chicago Defender heaps on ‘Yardbird’ for his contributions to jazz, they neglect to mention why this was his nickname. The answer is provided in another national edition five years later:

The anonymous author describes a person that, trapped within the gritty and difficult world of the inner-city, finds consolation in thinking about Bird and memorializing him through graffiti. For him, Bird (Parker himself as well as the nickname) symbolizes the ability to know “the freedom inside his head that allowed him to dream- and fly up, out and away” from the challenging circumstances of his life.[2] The author invokes the name of Dadelus, the Greek man who dreamt to fly away from his prison cell via his own ingenuity. Dadelus serves as a parallel to Bird, who used his innovative music to fly away the past and change the landscape of jazz, becoming a mythological figure in his own right.

With these two articles together, it almost seems as though the latter serves as a direct answer to the former. Bird’s music will not die because people’s dreams will not die. And as long as people continue to dream, the creativity and passion of Bird will be memorialized in both stone and flesh. The connection of flight and dreams as they relate to Parker remained relevant into the 1960s, as jazz musicians reacted to the development of the civil rights movement. As Bird did before them, they used their own perspectives to mold jazz into an expression of freedom. Bird and his music lived on, and will continue to as long as musicians continue to dream.

[1] Special. 1955. “Death of ‘Yardbird’ Parker may Affect Bebop’s Fight to ‘Live’.” The Chicago Defender (National Edition) (1921-1967), Mar 26, 6. http://search.proquest.com/docview/492930917?accountid=351.

[2] F.L.B. 1960. “Bird Lives.” Daily Defender (Daily Edition) (1956-1960), Apr 04, 1. http://search.proquest.com/docview/493786203?accountid=351.