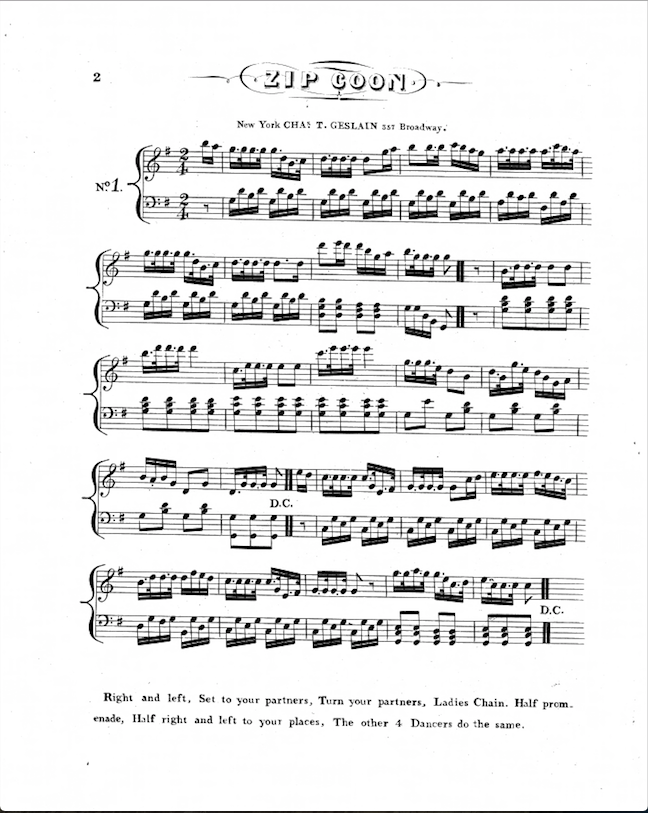

Almost all of us know the melody of “Turkey in the Straw,” whether singing it at summer camp when we were kids or singing along with The Wiggles before school. The song “Zip Coon” is also based off of same melody and was most popular in the 1830’s and 40’s when it was sung in minstrel shows to depict the “coon” stereotype. Despite its controversial racist lyrics, the melody is catchy and works well for dancing.

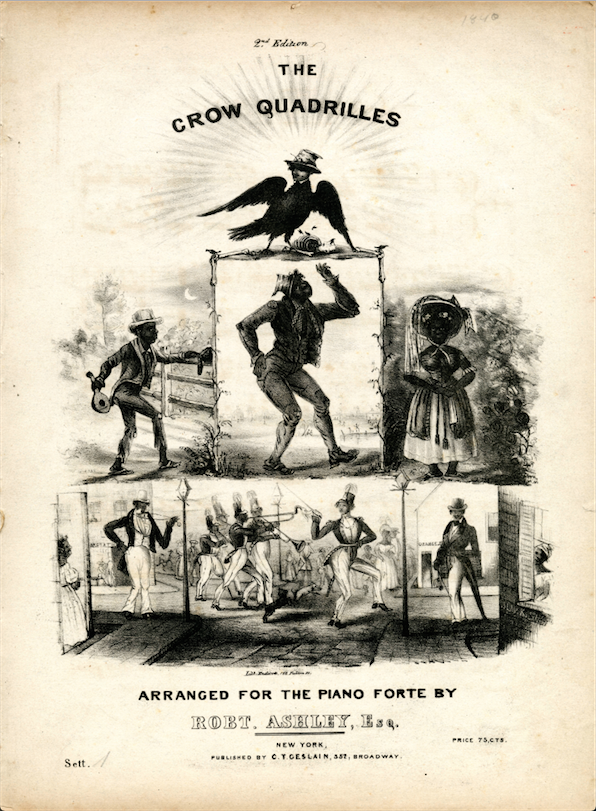

When minstrelsy was becoming popular, so were the tunes that were being performed. What better way for people to enjoy these famous songs but to dance to them as well? One of the popular dance forms during the 1840’s was the quadrille, which is related to square dancing today. It contained six parts and four couples would dance in a square formation. This composition features six popular tunes from minstrel shows, including “Zip Coon” and “Jim Crow,” and uses these tunes as the six parts of the quadrille. The cover features depictions of many famous minstrel show stereotypes.

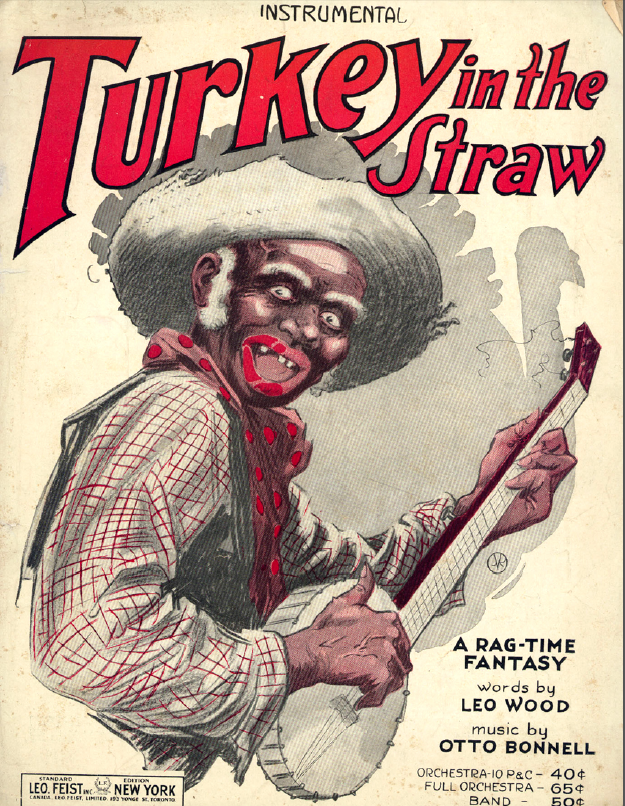

By the 1920’s, slavery was abolished with the Thirteenth Amendment to the Constitution in 1865 following the American Civil War. However, segregation remained strongly prevalent throughout the United States. The mindset of white supremacy among non-African American citizens pervaded even into their music. In this arrangement of “Turkey in the Straw” by Otto Bonnell and arranged by Calvin Groom, the cover of the sheet music features an African American man playing a banjo.

Or so it seems.

Upon closer inspection, the depiction of the man is clearly referencing blackface. When compared with the cover of “The Crow Quadrilles,” the large eyes and clown-like red lips are a means of hearkening back to the “good old days” of minstrelsy. The man is also missing teeth and his hands have an animalistic quality to them, characterizing the African American as less than human.

The tune of “Turkey in the Straw” is set as an innocuous foxtrot in this arrangement with no racial implications. However, with the cover depicting African Americans in such a condescending fashion, it is clear the intent of the music is to invoke a feeling of nostalgia to a time when white men owned slaves. In that case, this piece is not any less offensive today than “The Crow Quadrilles.” Instead of titling it “Turkey in the Straw,” it may have just as well been labeled as a foxtrot based on “Zip Coon.”

1. Ashley, Robert. “The Crow Quadrilles.” New York City, NY: C.T. Geslain, 1845. http://digital.library.temple.edu/cdm/ref/collection/p15037coll1/id/6875.

2. Bonnell, Otto. “Turkey in the Straw.” Arr. by Calvin Grooms. New York City, NY: Leo Feist Inc., 1921. http://digital.library.msstate.edu/cdm/ref/collection/SheetMusic/id/24823.