Shape notes are a style of music notation most popularly printed in the songbooks of The Sacred Harp, and is categorized as sacred choral music. Shape note singing originates in the New England region of America as way to help illiterate Americans read music and participate more freely in religious activity. This style of si nging was mainly found in the Protestant sect of Christianity. Shape notes reinforce the importance of congregational style of singing in church, allowing for a broader inclusion of church-goers.

nging was mainly found in the Protestant sect of Christianity. Shape notes reinforce the importance of congregational style of singing in church, allowing for a broader inclusion of church-goers.

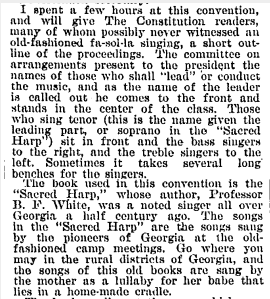

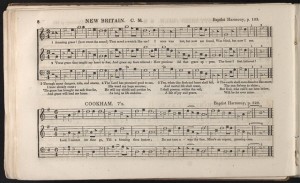

The first iteration of shape note notation, invented by Psalmodist Andrew Law, was meant to simplify singing by assigning different shapes to different syllables (fa, sol, la, and mi) so that singers knew which syllables to sing without needing to read lyrics. In 1801, the system was developed by William Little and William Smith and assigned these shapes to different pitches on a staff. This resulted in the creation of The Sacred Harp tunebook. In an article posted in the Common School Advocate in the year 1838, the tunebook was regarded as “decidedly the best and most permanently useful work yet published… made up of the finest compositions of the great masters of ancient and modern times, with new music.” A review that pays homage to the times, as this was a fairly new invention that gave a church goers a new and inclusive experience participating in the singing of psalms and hymns.

A popular hymn that is sung today that The Sacred Harp transcribed into shape note notation is “Amazing Grace.” Largely sung at funerals, this originally baptist tune transcribed in shape note notation is a great example of the choral music of the Antebellum south period. The Christian Observer, an Anglican evangelical periodical that existed between 1802 and 1874, wrote highly of the Sacred Harp tunebook, posting numerous recommendations of its publication. One that particularly stood out, read “ The volume is composed of very beautiful melodies; and harmonies of almost unequalled richness… The tunes are admirably adapted to the effective expression of poetry, a circumstance upon which the happiest effect of Christian Psalmody depend.” A boasting review of a simple style of music, which goes to show the nature of music during this time period in America. Neither monophonic nor polyphonic, this unique style, which is heterophonic in texture, has a surprising sound that is unfamiliar, even to a trained ear. The more popular hymnody has a far more recognizable polyphonic texture that most trained and un-trained ears are accustomed to.

The volume is composed of very beautiful melodies; and harmonies of almost unequalled richness… The tunes are admirably adapted to the effective expression of poetry, a circumstance upon which the happiest effect of Christian Psalmody depend.” A boasting review of a simple style of music, which goes to show the nature of music during this time period in America. Neither monophonic nor polyphonic, this unique style, which is heterophonic in texture, has a surprising sound that is unfamiliar, even to a trained ear. The more popular hymnody has a far more recognizable polyphonic texture that most trained and un-trained ears are accustomed to.

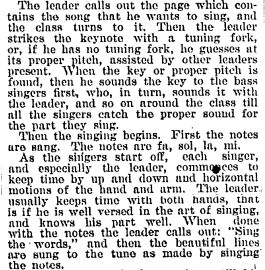

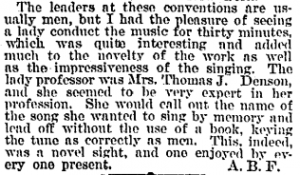

At the annual conventions, there is a specific structure to how they sing each song, whether or not that is how it was performed in 1850 is unbeknown to me, but the format is as follows: “sung through once on the solfege syllables, then sung in its entirety, with the final phrase repeated as a conclusion” (Miller). Despite the repetitive nature of such singing style, the participants are very enthusiastic in their singing of such tunes, and often clap and stomp along with the beat. Through shape-note singing a community emerged, one that is based around the Protestant faith, but is much more than that.

Shape note notation is important in American music history, as it is seen as the first original American music style and it is a defining style that influences genres to come. Some music historians say that African American spirituals were influenced from the shape note singing of groups like the Sacred Harp. If this is in fact true, the shape note style is an important one in American history that continues to influence music today.

Bibliography

Miller, Sarah Bryan. Post-Dispatch Classical, Music Critic. “Amazing Grace at The Missouri Sacred Harp Convention, Shape-Note Singing Isn’t for Listening, It’s for Participation.” St. Louis Post – Dispatch, Mar 28, 2001.

“VALUABLE MUSIC BOOKS,” 1841. Christian Observer (1840-1910), Oct 29, 176. http://search.proquest.com/docview/136098231?accountid=351.

“A VALUABLE music book,” 1838. Common School Advocate (1837-1841), Vol. 14: pp. 95. http://search.proquest.com/docview/124760960?accountid=351

http://originalsacredharp.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/1-First-Ireland-Convention.jpg

http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/4/47/New_Britain_Southern_Harmony_Amazing_Grace.jpg