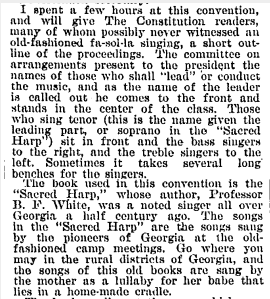

When I walked into Print Study Room in St. Olaf College’s Dittman Center, the first painting that caught my eye was this one of Walt Whitman. I was drawn to it because I recognized the subject. I can’t say I knew exactly what Whitman looked like beforehand, but I knew figure in the portrait was probably him. A wise looking older man with a beard of pure white wearing simple, earth-toned clothes–now this had to be America’s transcendental literary hero!

So, I was not surprised to pull a tag from behind the frame that read “Walt Whitman;” nor was I surprised to learn that the painter, Xanthus Russel Smith, was best known for his Civil War paintings. Why? Because this painting is a portrait. Portraits are created with intent. Unlike a beautiful landscape a painter happens upon or an idea a painter wants to portray visually, a portrait exists to honor a person. They are often planned and commissioned and sometimes even created for a specific room or occasion. Portraits depict heroes. That is why it made sense that the painter of this portrait also made Civil War paintings. Smith must have been interested in portraying what heroism in America looked like 19th century, and he chose Walt Whitman to be one such example.

My second guess, if this had not been Whitman, was Charles Ives. If not America’s literary hero, perhaps it was America’s musical hero! Ives certainly would have been deemed worthy of a portrait as well. Though the style of the clothing looked a bit old, I thought it could be Ives because of the subject’s white beard and older age. Then, I realized that–though the portrait could have been Whitman or Ives because they are both figures of American heroism–the main reason I knew it was either Whitman or Ives was because the man in the portrait was old. Why are the most well-known depictions of both Whitman and Ives of them as old men?

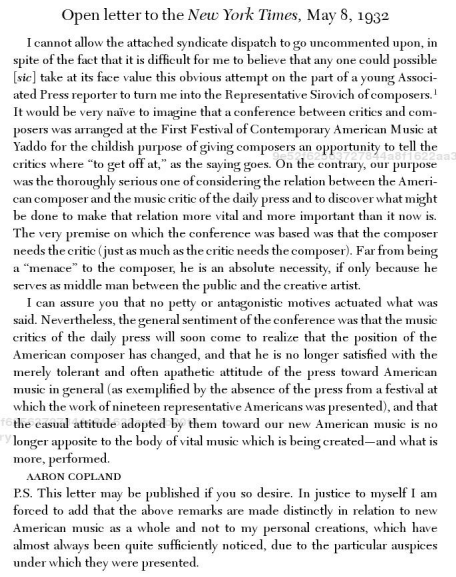

It must be because both of them were exalted by artists of the younger generation. Beat writers like Allen Ginsberg and Jack Kerouac adopted his vagabond lifestyle and imitated his anaphoric style in their own writing. Ezra Pound said of Whitman, “he is America.” So though Whitman was writing in the 19th century, his works became very popular in the 20th century. Similarly, Ives was composing in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, but his works did not become popular until the mid 20th century, when composers like Henry Cowell and Aaron Copland promoted them.

Both Whitman and Ives were recognized long after their work was published and held up as examples of the American spirit. They both embodied the American tradition of individualism, originality, and self-sufficiency. Had Whitman lived in Massachusetts, he perhaps could have made it into Ives’s Concord Sonata. Passing down these American traits, like father and son, Whitman and Ives make me wonder if we have a current day example of the American artist as an old (white) man. Clint Eastwood? Or have we moved beyond this narrow definition of America (at least now we recognize that Whitman was gay!) to include American heros of different ethnicities, races, genders, sexualities, and ages? Who do we paint portraits of today?

Figure 2

Figure 2 Figure 3

Figure 3