Artists have an ongoing love-hate relationship with critics in the press. Whether reviewers of artistic works use their words to uplift or pick apart what they’ve seen and heard, it feels like performers, producers, and audiences alike put too much emphasis on the words of critics. While I myself am certainly a fan of giving my own lengthy monologue detailing the highs and lows of any musical production I see only moments after exiting the lobby, my words are rarely given a hint of importance offered to those that take to newspapers and online sites to review professional productions. But, how important are the thoughts and words of these critics?

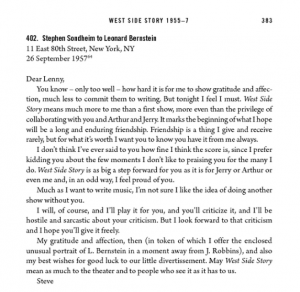

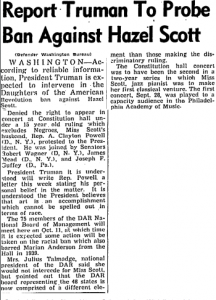

This question came to a head when looking for newspaper reviews for the original Broadway production of West Side Story in 1957. As a #megafan, I new that initial reviews of the work were mixed, and that the work aged quite well despite initial concerns from critics. In an article from the Daily Defender published in 1958, I though in perplexing that a review of the recent Broadway season listed a musical I had never heard of.

As seen in the article above, the show used in what should be the attention-grabbing title of the article was not my beloved West Side Story, nor the Tony-Award-winning-for-best-musical The Music Man, rather a musical entitled Jamaica. A quick google search of the musical shows an initial success and relatively positive reviews along with a slew of Tony Award nominations, but also a show that hasn’t aged well due to its musical choices and a sort of cultural cringe factor evident in too many creations of a racist America.

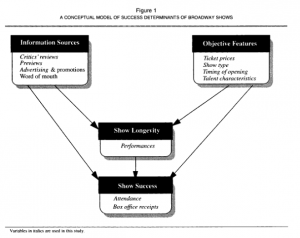

So this still leaves my original question unanswered: Do the voice of critics really matter? What impact do they have? It appears that to get this answered, we must follow the money (or, as the kids say these days, “show the receipts” *clap clap*). There has been scholarship that factors the opinions of critics into statistical models of successful and not-so-successful musical theatre endeavors (as well as other forms of arts and entertainment).1 While it appears the opinion of critics rarely shows any correlation of commercial success with theatrical productions, scholarly models note the importance of the opinions of critics in forming audience interest and ideas about the production prior to possibly seeing it or buying a ticket

So, I guess my conclusion here is that critics don’t always get it right. While they might think their educated inferences should ultimately dictate the fate of the Broadway musicals they struggle to sit through or heartily applaud, the reality is much more complicated. When I came across the newspaper article, I was confused about how the review of a Broadway season somehow featured a now unknown and unperformed musical at its heading. But hindsight is 20/20, and I have the luxury of time that was not afforded to the critics writing in the heat of battle on The Great White Way.

A quick P.S.: while it is certainly arguable whether we should look at money and commercial success as the main factor for determining a successful piece of art, this blog post fails to engage in that conversation. That is another topic for another blog post/paper/thesis/lifetime of research.

Primary Source

“Jamaica’ Tops on Broadway.” Daily Defender (Daily Edition) (1956-1960), Jan 07, 1958. https://search.proquest.com/docview/493716192?accountid=351.

Secondary Source

1 Reddy, Srinivas K., Vanitha Swaminathan, and Carol M. Motley. “Exploring the Determinants of Broadway Show Success.” Journal of Marketing Research 35, no. 3 (1998): 370-83. doi:10.2307/3152034.