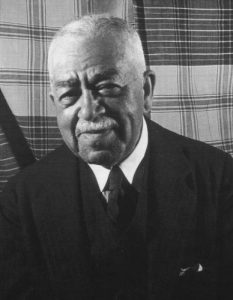

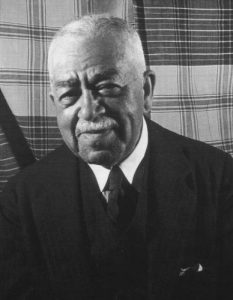

One of the most beloved African-American composers of the late 19th and early 20th centuries was Harry T. Burleigh. Born and raised in Erie, Pennsylvania, he learned to sing spirituals from his mother and sang in various church and community events throughout his childhood. In his teenage years, he became known as a fantastic classical singer, and got to work at and see many famous people perform, such as Venezuelan pianist Teresa Carreño. Then, a few years after high school in 1892, Burleigh began to attend the National Conservatory of Music in New York on scholarship for voice (1).

But, by the title of this blog post, how does any of this relate to Czech person and well-known composer Antonín Dvořák?

Well, Dvořák happened to immigrate the United States in 1892 also to become the director of the National Conservatory of Music! He both taught classes and conducted the conservatory orchestra, which Burleigh also happened to become the librarian and copyist for. As a result of this, Dvořák and Burleigh worked together frequently, which eventually turned into a friendship. A particularly cute story from their friendship comes from a letter Dvořák wrote to his family back home that his son “[would sit] on Burleigh’s lap during the orchestra’s rehearsals and [play] the tympani” (2).

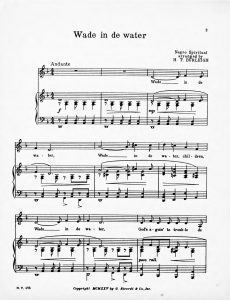

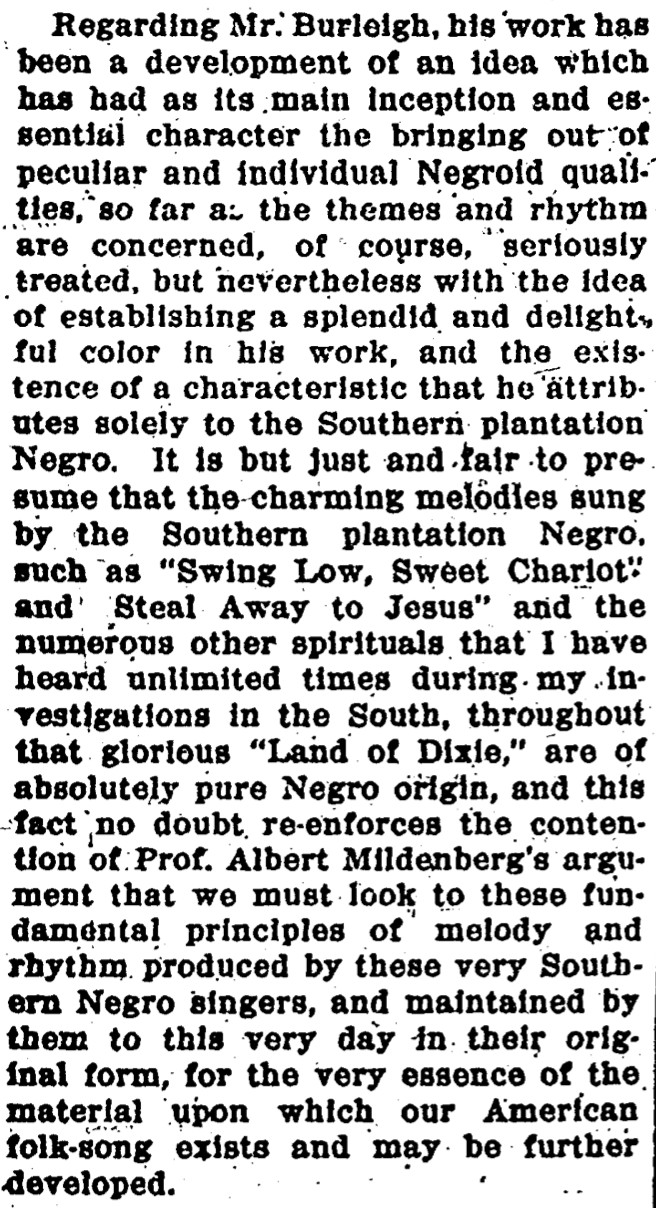

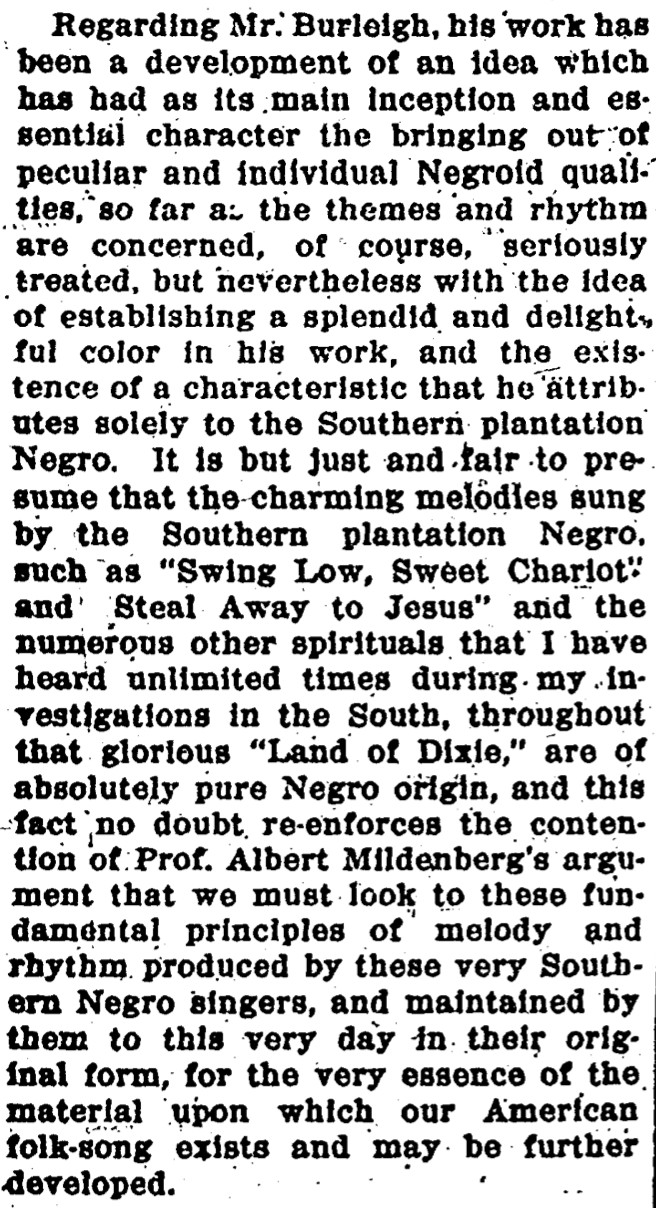

However, the relationship between the two bettered their compositions as well. Dvořák would often overhear Burleigh singing spirituals to himself while working or in the halls, and, not knowing much about spirituals, would talk to him about them and learn many of the songs from him. Dvořák then encouraged Burleigh to begin composing and arranging these spirituals (1). This would kickstart a prolific composing career for Burleigh, who incorporated spirituals into many of his original art songs, arrangements, and other compositions, and amassed a portfolio of over 200 works. Here is a review of his works from the Afro-American Cullings section of the Cleveland Gazette (3):

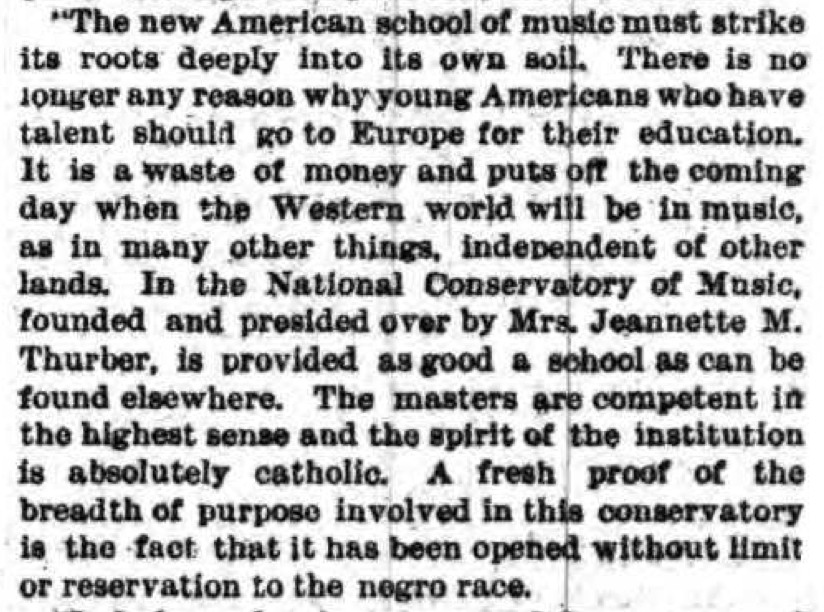

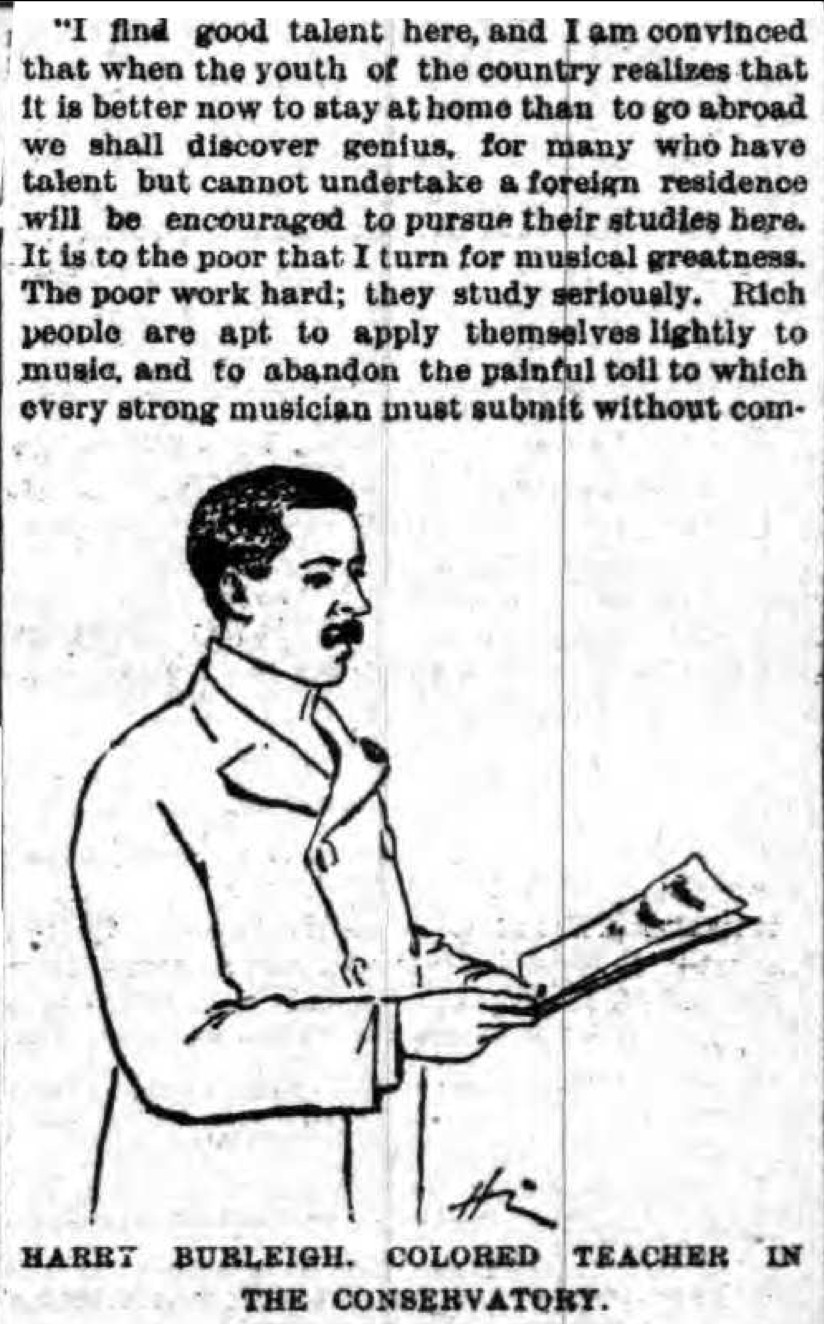

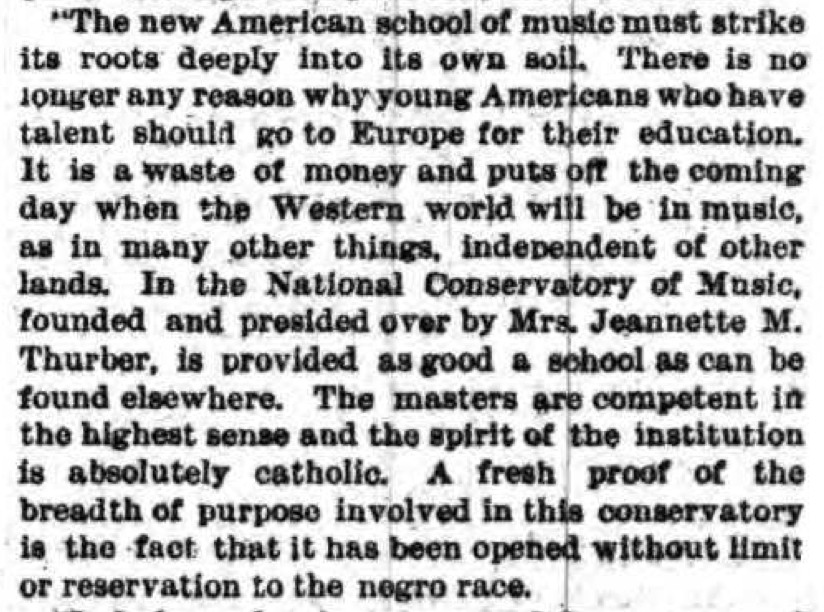

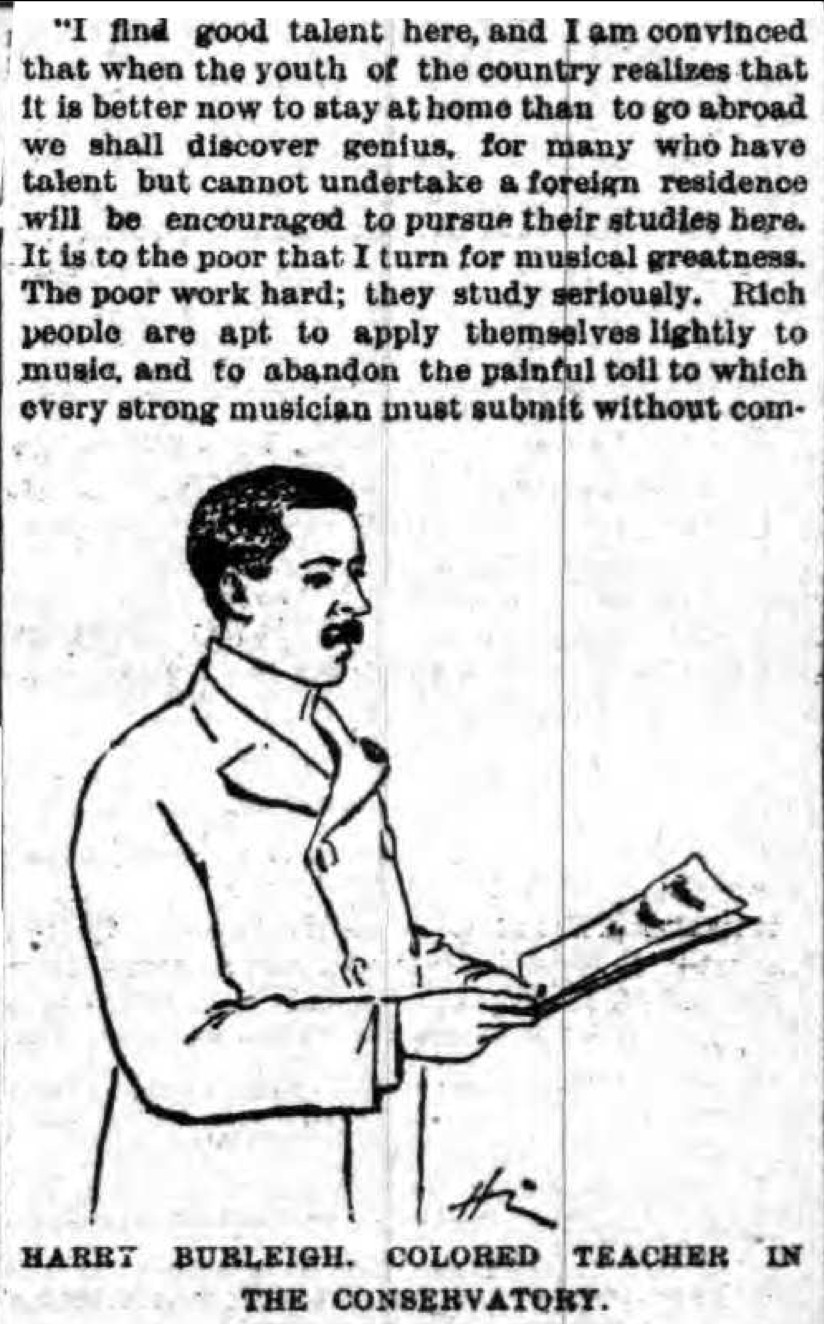

Dvořák also found ample inspiration in the African-American folk music he learned from Burleigh and gained a huge amount of respect for it. In fact, he was so displeased that white Americans did not care for African-American music that wrote several news articles in the New York Herald, in which he argued that the soul of American music lies in Black music, which the Herald’s white readers found difficult to swallow, to say the least. Here are a few words from an article he wrote in 1893, with even a picture of Burleigh (4):

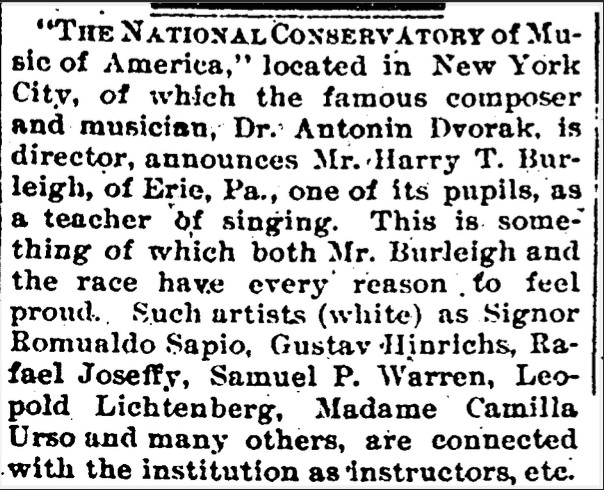

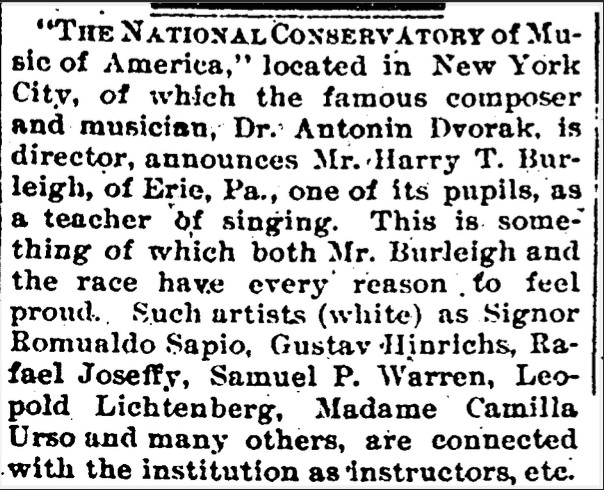

Dvořák then composed his New World Symphony (here’s a link to its very famous Largo movement) based off several spirituals, the pentatonic and blues scale – all learned from Burleigh – and Indigenous music, and it gained massive acclaim and spreading rapidly throughout the country (3). Black communities across the country absolutely adored the work, and grew to become very fond of and proud of both Dvořák and Burleigh, as can be seen in this from the Cleveland Gazette (5): Thankfully, and radically for the time, Dvořák gave much credit to Burleigh for the conception of many of the ideas for his New World Symphony (2). One can debate the ethicality of Dvořák’s quotation of Black and Indigenous music within his own music, but at the very minimum, he supported and credited those who inspired him.

Thankfully, and radically for the time, Dvořák gave much credit to Burleigh for the conception of many of the ideas for his New World Symphony (2). One can debate the ethicality of Dvořák’s quotation of Black and Indigenous music within his own music, but at the very minimum, he supported and credited those who inspired him.

Sources:

(1) “H. T. Burleigh (1866-1949)”. 2022. The Library Of Congress. https://loc.gov/item/ihas.200035730.

(2) “African American Influences”. 2022. DAHA. https://www.dvoraknyc.org/african-american-influences.

(3) “Afro-American Cullings.” Cleveland Gazette, October 30, 1915: 4. Readex: African American Newspapers. https://infoweb.newsbank.com/apps/readex/doc?p=EANAAA&docref=image/v2%3A12B716FE88B82998%40EANAAA-12BC1B62334A2850%402420801-12BA063BD57BDCD8%403-12DBB540D0E6C840%40Afro-American%2BCullings.

(4) Dvořák, Antonin. 1893. “Antonin Dvořák On Negro Melodies”. New York Herald, May 28th, 1893. https://static.qobuz.com/info/IMG/pdf/NYHerald-1893-May-28-Recentre.pdf.

(5) “[America; Dr. Antonin Dvorak; Mr. Harry T. Burleigh; Erie; Samuel P. Warren].” Cleveland Gazette, September 23, 1893: 2. Readex: African American Newspapers. https://infoweb.newsbank.com/apps/readex/doc?p=EANAAA&docref=image/v2%3A12B716FE88B82998%40EANAAA-12C2B9DB2DFFBDD8%402412730-12C106453A9F6688%401-12D7B8B19C518AD0%40%255BAmerica%253B%2BDr.%2BAntonin%2BDvorak%253B%2BMr.%2BHarry%2BT.%2BBurleigh%253B%2BErie%253B%2BSamuel%2BP.%2BWarren%255D.

3

3