We all have heard of The Supremes, Stevie Wonder, and the Jackson 5, but where did Motown come from and how has it been important? Whenever I think of Motown my mind jumps straight to the thought of Detroit. The … Continue reading

Author Archives: Kelsey Anderson

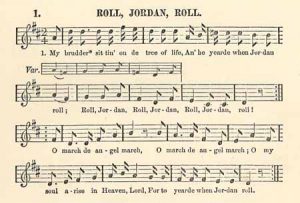

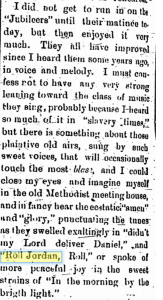

The History and Reception of “Roll Jordan, Roll”

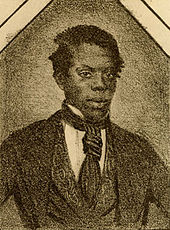

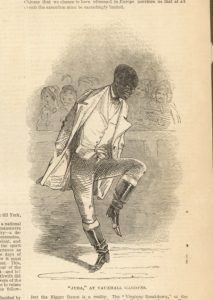

William Henry Lane “Master Juba”

William Henry Lane, know as “Master Juba” on stage, was the most renowned black stage performer prior to the 1850’s. William performed with minstrel shows (Ethiopian Serenaders) and toured not only in the U.S. but to Europe. He was the first African American to perform in England. He was a famous performer and is arguably a main attributer and constituent to what we now call tap dance.

From Eric Lott’s Love and Theft: Blackface Minstrelsy and the American Working Class we know that African Americans dressing up and putting cork on their faces was a known thing, but Lane had done this in a time that was a prequel to thus. Lane had seemingly found success in the minstrel circuit.

Lane was a huge success over in England and the rest of Europe. An English critic after seeing Lane perform said:

Juba’s whirlwind style [was] executed with ease and “natural grace.” “[Such] mobility of muscles, such flexibility of joints, such boundings, such slidings, such gyrations, such toes and heelings, such backwardings and forwardings, such posturings, such firmness of foot, such elasticity of tendon, such mutation of movement, such vigor, such variety . . . such powers of endurance, such potency of ankle. (Conway)

Many viewers had a difficult time describing Lane’s style of dancing. It was upbeat and followed closely to the percussion of the music. It is argued whether the inability of others to describe his dancing style was do to his African background and whether he brought pieces of African dance into his style or not. Regardless, Lane became a sensation.

Lane and his style of dancing was so renowned that he had been mentioned in the works of Charles Dickens. He lived a hectic and short life, “records indicate Master Juba lived the intense life of a touring performer, giving shows every night. He also opened a dance school in London” (Peters). Unfortunately, Lane passed away in his late 20s in England.

Works Cited:

Lott, Eric. Love and theft: blackface minstrelsy and the American working class. Oxford University Press, 2013.

Railroad Songs and Gandy Dancers

Railroad songs were a genre created by laborers for the railroads in America. The origin of the genre is disputed and rather mysterious. We can all recall “I’ve been Working on the Railroad” (pre Civil War), but it is unclear if that is one example of the genres earliest pieces. Archie Green suggests in “Railroad Songs and Ballads: From the Archive of Folk Song” that “[the songs] welled directly out of the experiences of workers and were composed literally to the rhythm of the handcar. Others were born in Tin Pan Alley rooms or bars. But regardless of birthplace, songs moved up and down the main line or were shunted onto isolated spur tracks.”1 John Lomax had recorded many of these railroad songs. Here is an example of one: http://www.loc.gov/item/lomaxbib000326/ 2

These songs were created by workers to entertain and convey stories up and down the rails. The subjects of the songs, that are recorded, range from the erotic, basic railroad construction, and common themes like love and loss. The creators of the railroads songs included African Americans and many immigrant people. Unfortunately there are little to no record of the songs created by immigrants in different languages and today there is no way of rediscovering those songs. These songs created by African Americans and immigrants created a new slang term for these people called “Gandy Dancers”.

In the article “Country Music and the Souls of White Folk” by Erich Nunn, we get a sense of the effect that the Gandy Dancer’s music has had on country music, we are told, “In My Husband, Jimmie Rodgers, a biography of her late husband published in 1935, Carrie Williamson (“Mrs. Jimmie”) Rodgers presents Jimmie as a crucible in which the “darkey songs” he learned as a boy are transmuted by “the natural music in his Irish soul” into something distinctive and new.”3 The songs that Carrie writes on were created by the African American men that worked of the rails and influenced Jimmie Rodgers.

Gandy Dancers used their songs as a method of keeping rhythm for the laborers of the railroad and striking in time amongst the laborers. Here is a short snippet of a documentary done on Gandy Dancers: 4

- Green, Archie. “Railroad Songs and Ballads.” Archive of Folk Song, 1968. Accessed February 26, 2018. https://www.loc.gov/folklife/LP/AFS_L61_opt.pdf.

- Lomax, John A, Ruby T Lomax, and Arthur Bell. John Henry. near Varner, Arkansas, 1939. Audio. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/lomaxbib000326/. (Accessed February 26, 2018.)

- Nunn, Erich. Country Music and the Souls of White Folk. Wayne State University Press.

- Folkstreamer. “Gandy Dancers.” YouTube. June 23, 2008. Accessed February 26, 2018. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=025QQwTwzdU.

The Grass Dance and Ankle Bells

Image

From the accounts of early settlers and newcomers to America, from Judith Tick’s Music in the USA : A Documentary Companion we know that Native Americans used drums, flutes, canes, and rattles in their music.1 I have been to the Mahkato Association’s Pow Wow in Mankato, MN a few times and there was a certain instrument that was not only decorative to the attire, or regalia, of the Native American dancers but to the rhythm and beat of the music. Many of the dancers wore bells on their ankles to add an element to the dance or what is called the “Grand Entry”.

The ankle bells appear in the Grass Dance that has been passed down and is still performed and preserved today by many tribes originating from the Great Plains region. According to the descendents of Omaha-Ponca and Dakota-Sioux tribes, this dance is so integral to these tribes today because “in an attempt to stabilize during a period of rapid cultural conversions by the United States government, it became important to both preserve and spread dances—including the merging of many tribal dances that formed what we now know as grass dance—to preserve indigenous unity.”2

The bells in the Grass Dance, and other dances like the Grand Entry, help keep the rhythm with the beat of the music.2 These bells were often fastened to sheep skin and then tied to the ankle. These ankle bells can now today help represent the merge of tribes during a difficult time and the effort that has gone into preserving dances. The bells that appeared in the Pow Wow in Mankato are a part of an annual event that remembers and aims to reconcile the 38 lives that were lost as a conclusion to the Dakota War in 1862.

- Tick, Judith, and Paul E. Beaudoin. Music in the USA: A Documentary Companion. Oxford University Press, 2008.

- ICT Staff. “Origins of the Grass Dance.” Indian Country Media Network. April 06, 2011. Accessed February 19, 2018. https://indiancountrymedianetwork.com/news/origins-of-the-grass-dance/.

- Peterson, Alfred. “Ojibwe ankle bells · Digital Public Library of America.” DPLA: Digital Public Library of America. Accessed February 19, 2018. https://dp.la/item/2ffa4bc517c99d0c0c2ab8d6cfe11a29?back_uri=https%3A%2F%2Fdp.la%2Fsearch%3Futf8%3D%25E2%259C%2593%26q%3D%2522ankle%2Bbells%2522&next=3&previous=1.

- Mahkato Wacipi. Accessed February 19, 2018. http://mahkatowacipi.org/index.php.