Founded in 1905, The Chicago Defender is an African-American run newspaper. In a 1935 publication, an article was published on composer Florence B. Price and her recent successes in composition. Most notably, she won prizes in the Wanamaker competition contest for her Symphony in E Minor and Piano Sonata in E Minor.

Price was a notable composer that brought black music to a wider, whiter, audience with her ability to incorporate Black musical idioms into symphonic works. Price’s Symphony in E Minor, which consists of three movements, was performed by the Chicago Symphony Orchestra at Orchestra Hall as well as at the Century Progress Exposition.

“Composer Wins Noteworthy Prizes for Piano Sonata.” The Chicago Defender (National Edition) (1921-1967), May 04, 1935. https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/composer-wins-noteworthy-prizes-piano-sonata/docview/492427674/se-2?accountid=351.

This news article in The Chicago Defender quotes Glenn Dillard Gunn’s of the Chicago Herald and Examiner thoughts on Price’s piano sonata,

“A nationalist in my attitude toward the art, it is pleasant for me to record the brilliant success of Florence Price’s piano concerto. It represents the most successful effort to date to lift the native folk song idiom of the Negro to artistic levels”1

Music critic of the Pittsburgh Sun-Telegraph was also quoted,

“Florence Price’s contribution in the form of a piano concerto was by far the most important feature of the concert for here we see what the Negro has taken from his own idiom and with good technique is beginning to develop alone. There is real American music and Mrs. Price is speaking a language she knows…”1

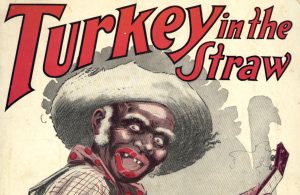

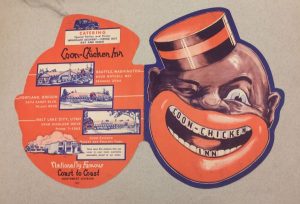

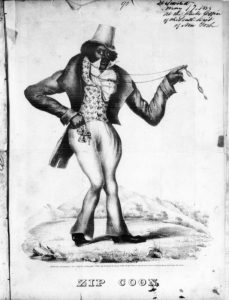

These ideas are also repeated and analyzed in Rae Linda Brown’s, “William Grant Still, Florence Price, and William Dawson: Echoes of the Harlem Renaissance”. 2 This chapter from Black Music and the Harlem Renaissance discusses Price’s role in society as a black art music composer that embodies the “American Sound”. Black composers during the Harlem Renaissance, Florence Price included, hoped to elevate black folk idioms to the symphonic form. I’m still grappling with the idea of “elevating” certain music to a white standard and the racism Price and other composers of the time had internalized when thinking of their own music.

Florence Price was a brilliant composer who did important work to include black artists and black music into the American music conversation. Yet, I think there’s work to be done on how we navigate these discussions on the hierarchy of music and specifically the interplay of race.