Aaron Copland, born November 14, 1900, is a composer best known for his incredibly accessible works, with pieces such as Appalachian Spring, Rodeo, and Fanfare for the Common Man being written in the 1930s and 40s. He was an American composer, although he studied in Europe for a good portion of his early career, and returned to America around the 1920s, where he lived in New York during the height of the quest to define what ‘American’ music was.

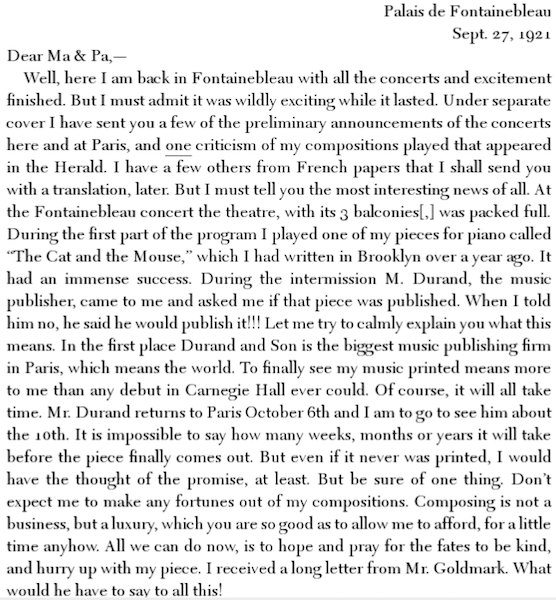

Copland composed in a great deal of styles, ranging from piano passacaglias to full symphonies. He was part of several jazz bands while in New York, as well as the League of Composers, and was well-known and respected, writing articles for their local magazine. One such piece was about George Antheil’s Jazz Sonata for piano, written in 1922, and was not well-received by the composer, although the original article perhaps did not warrant such a response. Copland wrote a letter to Antheil, perhaps to diffuse the situation, in which he notes:

The idea of writing that article came to me as a result of the reception given your Jazz Sonata at a concert earlier in the season. All the music critics took the stupid attitude that you were a mere bluff, trying to scandalize the musical public…1

Considering that Copland was part of several jazz bands, it can be assumed that he is referring here to the negative perception afforded jazz and similar genres, even when written by white composers, something prevalent surrounding the time of the early Harlem Renaissance, when such music was to be confined to night clubs only. Copland’s view of jazz seems to be very positive, demonstrating that he was open to a variety of music styles, especially considering that this piece was most likely performed in a concert with other works, that is to say as an art song rather than a dance number or similar. This may demonstrate the shift from jazz being considered a ‘scandalous’ genre to something worthy of a concert, something with legitimacy.

Copland’s view of the actual makers of jazz, that is to say the black community, has to be extrapolated from several different letters, as he says nothing explicit about his ideas about black musicians and performs. In one letter to Carlos Chavez, a Mexican composer of renown, he notes that “Kids are like Negroes, you can’t go wrong if they are on the stage.”2 This was in discussion about his opinion of the opera The Second Hurricane, and the child actors playing several roles within. A footnote in the Correspondence collection states that “Copland may have had in mind Four Sains in Three Acts, which sustained Gertrude Stein’s modernist libretto and Virgil Thomson’s music by means of its black cast…” which although not part of his actual letter gives some insight into Copland’s surroundings at the time of writing. Taking his sentence literally, he certainly seems to have a positive view of black performers, a view that is supported further by his thoughts on the ‘Negro Voice’:

What a music factory it is! Thirteen black men and me – quite a piquant scene. The thing I like most is the quality of voice when the Negroes sing down here. It does things to me – it’s so sweet and moving. And just think, no serious Cuban composer is using any of this. It’s awful tempting, but I’ll try to control myself.3

Although this excerpt comes from a letter to Leonard Bernstein from Havana, Cuba, written in 1941, it still is useful in giving insight into Copland’s views. He views the ‘black voice’ as something to be used more often in songs, something that is ‘sweet and moving’. Granted, this is in Cuba, not New York. There are different politics in play, and indeed, an entire different musical style. However, I believe that this is indicative of a general appreciation that Copland has for music, without much consideration for who is behind it. He has previously noted that the consideration of jazz as ‘scandalous’ is stupid, he has noted that ‘you can’t go wrong with Negro performers’ and then 20 years later goes to South and Central American and enjoys partaking in their musical traditions. In this way, a sliver of his view: that music should be appreciated and recognized, comes through.

Works Cited: