Buddy Bolden made a name for himself performing in Union Square. https://prcno.org/louis-sullivans-sophisticated-union-depot-welcomed-train-passengers-new-orleans-60-years/

One of the most informative sources I came across for my group’s project on the origins of jazz is an article published by historian James Karst on the Preservation Society of New Orleans’ website titled “Buddy Bolden, the father of jazz, left no known recorded music, but his home still stands in Central City”. Buddy Bolden, born as Charles Bolden, was a virtuosic jazz trumpet performer and one of the main contributors to the birth of the jazz genre. Bolden, likely influenced by brass bands on the streets of his Central City neighborhood in New Orleans, rose to fame for his cornet playing in Union Square (Marquis). Karst writes that “Sometime before the turn of the century, legend has it, he began to improvise passages in existing songs, perhaps because of his inability to play them as written or as others played them. The failure to play the music the way it was intended didn’t matter, of course. The people loved it. They supposedly would come from across the city to hear Bolden play.” This being said, I was surprised to have never even heard his name until we started our project. Bolden’s career ended abruptly with three arrests and his admittance into the State Insane Asylum in Jackson, Louisiana, which is probably the reason behind Bolden’s little physical records today.

Central City neighborhood where Bolden lived. https://thelensnola.org/2013/02/01/photo-essay-central-city-languishes-just-a-short-walk-from-the-glitzy-superdome/

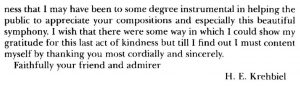

Like the title of Karst’s article suggests, there is no recorded music by Buddy Bolden that can be listened to today. Furthermore, the article states that there is only a single known picture of the jazz star. It is not even known where Bolden is buried. Karst uses uncertain language in the article that signifies to readers that not much is known about Bolden’s childhood, either: “He undoubtedly witnessed brass bands parading through the streets from the time he was a child. He probably went to the Fisk School [not to be confused with Fisk University, where the Fisk Jubilee Singers originated], the same school Louis Armstrong later attended, and may have even graduated. At some point, he began taking music lessons on the cornet,” (Karst) [Italicizations added to draw attention to Karst’s unsure wording].

The only known picture of Buddy Bolden. He is pictured second from left in the top row. Buddy Bolden’s childhood home. https://prcno.org/buddy-bolden-father-jazz/

These gaps in knowledge about Buddy Bolden’s life were not aided by his three arrests and consequential institutionalization. Bolden’s first arrest in 1906 (and likely his others) was connected to his deteriorating mental state as a young adult: “He had been bedridden for several weeks, according to newspaper reports on the incident from the time, including one recently discovered by this writer. In a fit of psychosis, Bolden became convinced that he was being drugged or poisoned, and he attacked his caregiver, who was either his mother or his mother-in-law. He was booked on a charge of being insane, and alcohol abuse was cited as the reason for his insanity,” (Karst). Karst writes that Bolden was arrested twice more in the following year, which eventually landed Bolden in the aforementioned State Insane Asylum. Bolden quit music due to struggles with his band and spent the rest of his life in the asylum. The little known knowledge about Bolden is likely due to his short-lived music career. This being said, it is amazing to consider the impact that Bolden had on the origins of jazz in such a quick time period. I wonder how many other incredibly influential American music are little known because of factors such as illness, lack of resources, imprisonment, or other similar issues?

Sources:

Karst, James. “Buddy Bolden, the Father of Jazz, Left No Known Recorded Music, but His Home Still Stands in Central City.” Preservation Resource Center of New Orleans, 30 Apr. 2019, https://prcno.org/buddy-bolden-father-jazz/.

Marquis, Donald M. In Search of Buddy Bolden : First Man of Jazz. Revised edition., Louisiana State University Press, 2005.