When John and Alan Lomax visited the Louisiana State Penitentiary of Angola, Louisiana in July of 1933 they were in search of folksongs. Little did they know that they would instead come across a musical star, whose treatment of a popular prison song would transcend the boundary between folk and pop styles. The musician was Huddie “Lead Belly” Ledbetter, and the song was “Midnight Special”.

Born in the late 1880’s to the oppressive cotton fields of Louisiana, Ledbetter feared only one thing: failure. It was from this determination that he received the nickname “Lead Belly”, as he could outwork, outfight, and out-sing anyone who dared challenge him. “I wants to be the best – the king” he would say. He even went so far as to call himself “The King of the Twelve-String Guitar”, a talent that he used to exploit the Texas prison system he entered in 1917 on a thirty year sentence for assault. He famously used his musical talent to garner the attention of Texas Governor Pat Neff, who pardoned and released Ledbetter from prison in 1925.

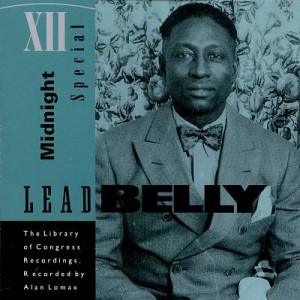

It was in this same spirit that he was brought to the Lomax’s attention in 1933. Incarcerated once again for assault, Ledbetter sufficiently wooed the Lomax’s that they convinced Louisiana Governor O.K. Allen to pardon Ledbetter. Thereafter, he worked as John Lomax’s chauffeur and relocated to the Northeastern United States, often traveling to Washington D.C. to record for Alan Lomax and the Library of Congress.

Midnight Special by Lead Belly, Library of Congress: http://www.loc.gov/item/ihas.200196310/

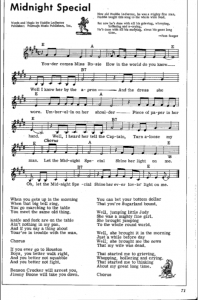

Volume I of the LOC collection is titled “Midnight Special”, and though it contains memorable treatments of many classic folk-tunes, the titular song is Ledbetter’s most famous and influential adaptation. Thought to originate among prisoners in the South, the refrain of the song references a passenger train of the same name, the light of which shone into cells as it passed by:

Let the Midnight Special shine her light on me, Let the Midnight Special shine her ever-loving light on me.

If the “ever-loving light” of the train landed on a prisoner, the inmates believed that man would soon be set free.

When Alan Lomax first recorded Ledbetter’s version of the song he attributed the authorship to Ledbetter. However, this is fundamentally untrue. In addition to the fact that it was a popular prison song, it had been recorded commercially by Sam Collins as the “Midnight Special Blues” in 1927. His version seems much more like an extemporaneous performance of a folk song, while Ledbetter’s is a precise arrangement of the melody, harmonic progression, and guitar accompaniment.

In this vein, it may be fair to say that Lead Belly didn’t write the song, but did ‘compose’ a version of it that achieved mass popularity and lasting influence in the public conception, as heard in versions by Creedence Clearwater Revival….

…. and ABBA.

While both versions seem to emerge from Ledbetter’s arrangement, the ABBA version is particularly notable due to its seemingly contradictory nature: why is a Swedish pop group performing an African American prison song? According to the official ABBA website, this song was performed as part of a medley of American folk songs on a charity record the group contributed to in 1975. The artists carefully selected songs that “were in the public domain as far as copyright was concerned” in order to avoid composer royalties. Despite this, the site recognizes Ledbetter’s “distinctive arrangement of the song that made it truly famous” as the inspiration for this version.

To conclude, “Midnight Special” exemplifies a major problem regarding folk music and its chronicling: differentiating between the folk song and popular versions. When do we lend credit to individuals and their renderings? How do we identify legitimate folk versions? While these questions may be difficult to answer, they ought to be considered as we examine popular reactions to folk music.

My mind has been blown, C, by that ABBA cover. That said, I think their cover is no stranger than CCR’s, or even Leadbelly’s for that matter. In fact, having heard a later (fuller) recording by Leadbelly first, what I find most interesting is how intent all the latter-day performers have been on normalizing what is fundamentally an off-kilter song. It’d be interesting to compare Leadbelly’s different versions and look at the contexts for which he was recording them. Did 20th-century (primarily white) audiences want their folk music to be authentic, but not too authentic, much like the earlier audiences of the Fisk Jubilee Singers? And then did white performers take a song by black prisoners and obscure its humility and faith, or can we still hear such things through the lyrics and through the good intentions of ABBA?

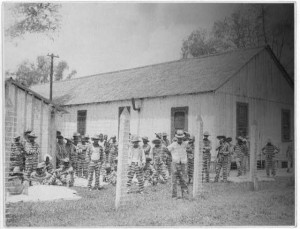

The photo you found is great, and it probably deserves a place in our library exhibit. If that is indeed Leadbelly leaning on the fence, staring at the photographer as if saying, “Finish taking my picture, then take me away from this place,” then it’s a powerfully symbolic image. Good work!