In the March of Time archives has a short video entitled Birth of Swing. The makers of this video trace swing back to around 1917 when the Dixieland Jazz Band was formed. The narrator explains that swing music has become extremely popular at the time of its creation (1937) and dives into the history of it. The video tells the story of a Victor Talking Machine (a brand of record player) music scout visiting a cafe where the pianist was playing a “kind of swinging music.” In response to being asked what his band’s name was, the pianist replied “Dixieland Jazz Band.” The scout decided to bring them from New Orleans to New York City to the recording studio. Since then they became extremely popular across the United States. This was when jazz started to become a term commonly used in the popular music idiom. Somewhere over the course of time between then and 1937, the term jazz however, had received negative connotations as a lowly, cheap kind of music and therefore was undesirable by white audiences. A simple marketing strategy to change the word on albums from “jazz” to “swing” enabled the popularization and dissemination of the music all throughout the country. And so during the days of the production of the video swing one of the most popular music genres in the country. Swing music, it gets concluded, was simply jazz music from an earlier period in American History.

Author Archives: guerra

HRR

Let me begin this post by apologizing for where I’ve acquired my artifact of the week. The assigned library to dig through was the Halvorson Music LIbrary, but while browsing St. Olaf’s Catalyst I found a book that I feel would be too valuable to our learning and the theme of this course not to write a post on. The Harlem Renaissance Revisited: Politics, Arts, and Letters by Jeffrey Ogbonna Green Ogbar is an amazing resource for anyone interested in looking at the Harlem Renaissance as a time period, or simply a person who wants to look at African-American identity and racial tensions in the United States in the 20th century. The book is made up of single chapters written by many different authors in order to cover a wide variety of topics and give readers a comprehensive view of the many different ways to view the problems addressed. The author divides these chapters into five different sections: Aesthetics and the New Negro, Class and Place in Harlem, Literary Icons Reconsidered, Gender Constructions, and Politics and the New Negro. Ogbar writes in his introduction of the book:

me begin this post by apologizing for where I’ve acquired my artifact of the week. The assigned library to dig through was the Halvorson Music LIbrary, but while browsing St. Olaf’s Catalyst I found a book that I feel would be too valuable to our learning and the theme of this course not to write a post on. The Harlem Renaissance Revisited: Politics, Arts, and Letters by Jeffrey Ogbonna Green Ogbar is an amazing resource for anyone interested in looking at the Harlem Renaissance as a time period, or simply a person who wants to look at African-American identity and racial tensions in the United States in the 20th century. The book is made up of single chapters written by many different authors in order to cover a wide variety of topics and give readers a comprehensive view of the many different ways to view the problems addressed. The author divides these chapters into five different sections: Aesthetics and the New Negro, Class and Place in Harlem, Literary Icons Reconsidered, Gender Constructions, and Politics and the New Negro. Ogbar writes in his introduction of the book:

“This volume brings together fresh perspectives from recent scholarship on the Harlem Renaissance. Although it covers only part of the story, it asks again what the Harlem Renaissance was all about, especially in terms of its major figures and its arts, letters and political landscape.”

I would highly recommend to anyone looking into any related topics for their papers to visit this book as a potential resource as there are many different scholarly voices present and though music isn’t the primary focus of this book, it does touch upon popular figures such as Gershwin and Ellington, but more importantly, as is written in the introductions, the book articulates the major figures of the time as well as the political landscape in which a lot of the music we’re studying was written and produced.

Ogbar, Jeffrey Ogbonna Green. The Harlem Renaissance Revisited : Politics, Arts, and Letters. Baltimore [Md.]: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2010.

St. Olaf in Blue

While browsing the Manitou Messenger archives, I came across an interesting article from March 12, 1965 entiteld Pop Concert Features ‘Rhapsody in Blue.’ The article is essentially an advertisement for a cabaret-style concert performed by the St. Olaf Band, Chamber Band, and several soloists from a then upcoming performance of the musical Camelot. According to this article, St. Olaf put on an annual concert of pop music which leads me to ask the question: what happened to it? Surely this event would have been popular among students within and outside the music department, by definition it surely was. The highlight of the concert during this year was a performance of George Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue. The piece was performed during the second half of the evening, in which the audience members sitting at tables with refreshments would switch places with audience members sitting in the bleachers. The final section of the concert was a performance from the Manitou Singers featuring The March of the Siamese Children from the musical The King and I.

St. Olaf’s Halvorson Music Library contains numerous copies of George Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue on vinyl records. I believe that this would be a great contribution to our museum exhibit. George Gershwin’s music was hugely influential as he was a central figure in the United States who combined the realms of jazz and classical art music in ways that provoked many to reconsider what they consider the boundaries of these two musical genres. It interesting to see how St. Olaf decided to feature this work during a pop music concert, clearly taking a strong stance that it does not belong in the typical art music world that St. Olaf has built its traditions on. Not that I necessarily agree with this decision, but I felt it was an important fact to point out. Although, any opportunity to perform Rhapsody in Blue is an opportunity worth taking, right?!

original article: http://stolaf.eastview.com/search/udb/doc?art=0&id=46103667&hl=Rhapsody

Amy Beach

Amy Beach was a prominent composer of American music during her lifetime. While I was browsing UCLA’s Sheet Music Consortium I was led to some interesting findings. However, much to my disappointment all of the artifacts I found were not accessible online and therefore I felt the need to search outside sources. I browsed the library of congress for Beach’s works. In it I found a sound text that I was familiar with, but in a different musical context. Because of this I was intrigued by it and decided to take a closer look at it. This artifact is Beach’s setting of the Shakespearian text Take, O Take Those Lips Away. This score is the second of three scores from a collection of Shakespearian texts set by Beach. The first and third being O, Mistress Mine, and Fairy Lullaby.

Beach was not only significant because she was a composer of American music, but that she was the first female composer of American music to gain success and recognition in the art music world. She was a musical prodigy. According to Grove Music Online

“At the age of one she could sing 40 tunes accurately and always in the same key; before the age of two she improvised alto lines against her mother’s soprano melodies; at three she taught herself to read; and at four she mentally composed her first piano pieces and later played them, and could play by ear whatever music she heard, including hymns in four-part harmony.”

As a vocalist, it’s hard to believe that these statements aren’t exaggerated, but it certainly emphasizes the point that Beach was an amazing musician who is definitely worthy of our attention as musical scholars.

Bibliography

Beach, H. H. A., Mrs, and William Shakespeare. Take, O take those lips away. Op. 37, No. 2. Arhut P. Schmidt, Boston, 1897. Notated Music. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, <https://www.loc.gov/item/ihas.200215426/>.

and . “Beach, Amy Marcy.” Grove Music Online. Oxford Music Online. Oxford University Press. Web. 23 Oct. 2017.<http://www.oxfordmusiconline.com/subscriber/article/grove/music/A2248268>.

Ayyyyye B.B.

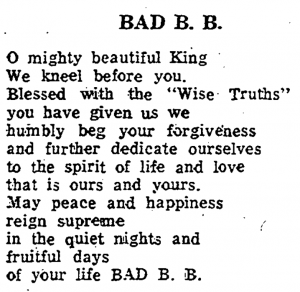

While browsing the Chicago Defender archives I discovered a newspaper article in which the author writes a short tribute to the legendary B.B. King. The author acclaims B.B. as well as other popular blues artists’ musical performance style saying that they communicate “simple and beautiful truth” that “touch[es] the inner core of black lives leaving us only to say, ‘he knows, he knows.'” In the poetic tribute, the author refers to B.B. as if he were a great king at the top of a royal ladder. He “beg[s] for forgiveness” and wishes to “further dedicate ourselves to the spirit of life and love that is ours and yours (B.B.’s).”

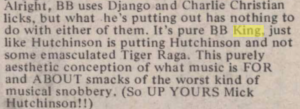

In the Popular Culture in Britain and America, 1950-1975 database I found another article praising B.B. King. The article in fact, was actually a response to comments made in a Mick Hutchinson interview. The author clearly has a strong opinion from the very first sentence in which he writes “In an interview with MickHutchinson (MusicIT/73) it was said among other stupidities, that BB King’s style lacked originality.” Clearly offended by these remarks, the author dives into an analysis of Mick Hutchinson’s musical ability in which he claims Hutchinson “can’t MOVE people, he hasn’t anything to lay on them.” The argument made is that though B.B. King is known for using simpler melodies and licks, he conveys far more meaning in it than Mick Hutchinson ever could. And if that wasn’t enough, the author even finishes the paragraph with an aggressive “(So UP YOURS Mick Hutchinson!!).”

Nina Simone: Little Girl Blue

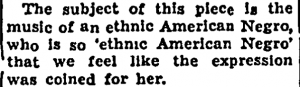

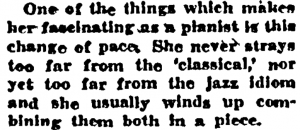

In her Los Angeles Tribune article published in 1959, Almena Lomax reviews the newly released debut album Little Girl Blue by Nina Simone. In this review, she traces Simone’s influences to several big-name jazzers at the time including, but certainly not limited to Duke Ellington, Billie Holiday, and Louis Armstrong. The article also notes of how Simone draws upon her classical piano studies and how she freely dances across the lines of classical and jazz styles, combining them in such a way as to never stray too deep into one of those musical territories, but consciously being aware of the genre mixture she was playing with. In this respect she also can be compared to George Gershwin, from who she also draws much inspiration, this is evident by her cover of “I Loves You, Porgy” from Gershwin’s Porgy and Bess. The article further goes to suggest that Nina Simone is “ an ethnic American Negro who is so ‘ethnic American Negro’ that we feel like the expression was coined for her. Already ecstatic about her quick rise to fame, little did the author know that Nina Simone would eventually become a common household name and her music a staple in the American Jazz idiom. Now we face the question: was Lomax right? On the one hand, to say that N ina Simone’s music is a holistic representation of African American music is certainly inaccurate. However, Simone’s influence over not only African American music but all of American popular music from the time she first released her Little Girl Blue even to the present day still goes strong. We can see this through numerous recordings and live performances of her music put on by contemporary jazz and popular musicians today.

ina Simone’s music is a holistic representation of African American music is certainly inaccurate. However, Simone’s influence over not only African American music but all of American popular music from the time she first released her Little Girl Blue even to the present day still goes strong. We can see this through numerous recordings and live performances of her music put on by contemporary jazz and popular musicians today.

Nina Simone For Lovers. Cond. Hal Mooney and Horace Ott. Rec. 25 Jan. 2005. Verve Records, 2005. Music Online: Jazz Music Library. Web. 9 Oct. 2017.

TY - NEWS N1 - Provider: NewsBank/Readex, Database: America's Historical Newspapers, SQN: 12C5FE5C375C5530 TI - Notes for Showfolks by Almena Lomax an Ethnic American Negro PY - 1959/12/04 JF - Los Angeles Tribune VL - 19 IS - 43 SP - 19 CP - Los Angeles, California ER -

Sinful Tunes and Spirituals: Black Folk Music to the Civil War

In her book entitled Sinful Tunes and Spirituals, Dena J. Epstein explores black folk music in the United States up til the civil war. The tunes analyzed are all slave songs that have been notated on musical staff paper, something that is inherently separate from the traditio ns that black folk musicians established in their practice. These songs were all sung by slaves, mostly in the fields where they worked. Sometimes these songs were used to communicate messages, making use of metaphors or other poetic techniques that disguised their meanings to the slave owners that may have heard them, but to other slaves, the message would be clear. Through this kind of code, a sort of secretive communication started to develop. I believe that this book would make an excellent contribution to the museum exhibit because it provides high-quality scholarly insight into the history of black folk music and makes use of artifacts leftover from that time period where some of these songs were recorded in our standard western musical notation. This book also makes use of images to provide a supplemental visual aid to the reader to be able to picture the events and the parts of history that are described within it. Furthermore, there are tons of scores contained within the book, so if one wanted to attempt to recreate these songs in the present day, it would be possible to do so to some extent. Obviously, like we’ve mentioned in class, there are lots of stylistic performance techniques that are lost in the process of notating these songs, but having the notes at least preserves it in some sense as to not let it die out.

ns that black folk musicians established in their practice. These songs were all sung by slaves, mostly in the fields where they worked. Sometimes these songs were used to communicate messages, making use of metaphors or other poetic techniques that disguised their meanings to the slave owners that may have heard them, but to other slaves, the message would be clear. Through this kind of code, a sort of secretive communication started to develop. I believe that this book would make an excellent contribution to the museum exhibit because it provides high-quality scholarly insight into the history of black folk music and makes use of artifacts leftover from that time period where some of these songs were recorded in our standard western musical notation. This book also makes use of images to provide a supplemental visual aid to the reader to be able to picture the events and the parts of history that are described within it. Furthermore, there are tons of scores contained within the book, so if one wanted to attempt to recreate these songs in the present day, it would be possible to do so to some extent. Obviously, like we’ve mentioned in class, there are lots of stylistic performance techniques that are lost in the process of notating these songs, but having the notes at least preserves it in some sense as to not let it die out.

Epstein, Dena J. Sinful Tunes and Spirituals : Black Folk Music to the Civil War. Urbana, University of Illinois Press, 1977.

George Clutesi and a Nootka Farewell Song

The Nookta Native American tribe has its origins in modern day British Columbia. The Nootka Farewell Song performed by George Clutesi is not only a fine example of a conscious effort to preserve the Native cultures of the region but also it is an example of traditional Native American music being given some light in the mainstream culture of today. Clutesi was the first Tseshaht mainstream celebrity in Canada. He was a multitalented artist who acted, wrote, and was an expert on native cultures. As a child, Clutesi was forced into participating in an educational system where one’s native heritage and culture was seen as a negative attribute and whose goal was to erase it. Fortunately, even as a young child Clutesi knew that there was something fundamentally wrong with this ideology and rejected it completely through his artistic talents. The song I’ve linked below is a representation of what Nootka music sounded like during the 20th century. Notable features of the song include an ad libbed introduction sung as a solo, then when the main tune kicks in the drum beat starts pounding a steady beat that continues until the ad lib outro. At the same time, as the drum beat beings we hear a choir singing in unison quietly in the background. If it weren’t for Clutesi and his activist contributions to the preservation of Native societies’ cultures there would be many songs such as this one which would be lost in the universe, never to be heard again.