W.C. Handy is the “Father of the Blues”

Headline: Seen and Heard While Passing; Article Type: News/Opinion

Freeman (Indianapolis, Indiana) • 09-26-1914 • Page 6

W. C. Handy became the “Father of the Blues” when he titled his autobiography that same name in 1957. However, this legacy started decades sooner, when Handy published the first “blues” with “Memphis Blues” in 1912. This blues became an immediate commercial success.

I was interested by the fact that “Memphis Blues” was the first blues ever written down, so I tried to find an early review of the work. In 1914, an Indianapolis newspaper, Freeman, ran a review of Handy praising the “Memphis Blues.” What surprised me most was a comment near the end of the article,

[Memphis Blues’] rapid increase in popularity everywhere makes it a psychological study and it is bound to become a classic of its kind just as the real Negro compositions of Will Marion Cooke, Scott Joplin and other Negro composers are now considered to be the only real expression of the Negro in music and the only genuine American music.

The “only genuine American Music?” Have you heard “Memphis Blues?” In case you have not, here is an early recording of it from 1944 by Lu Watters’ Yerba Buena Jazz Band

Does that sound a little like ragtime to you? To me, “Memphis Blues” simply does not sound like what I know as The Blues. Of course, is this a problem? Furthermore, who am I to decide what the blues should sound like? Well, thankfully, we have musicologists for that.

Does that sound a little like ragtime to you? To me, “Memphis Blues” simply does not sound like what I know as The Blues. Of course, is this a problem? Furthermore, who am I to decide what the blues should sound like? Well, thankfully, we have musicologists for that.

In Elijah Wald’s book, Escaping the Delta, notes:

“[experts argue] that Dock Boggs was a blues singer but that W. C. Handy’s songs were ragtime… Musicologically, that makes sense.”

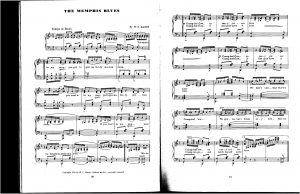

So I’m not crazy! There is something going on in “Memphis Blues” that makes it feel like ragtime instead of a blues! A further look at the sheet music published by W.C. Hardy indicates something unique… “Memphis Blues” is not in a standard 12-bar form! Its a 16-bar form. A 12-bar like figure appears in the chorus, but it is not clearly laid out.

Perhaps this was just an initial form that became updated over time. Perhaps my notion of “the blues” is simply chronologically later. I looked into another take on “Memphis Blues” by Louis Armstrong, and as you can hear it is just the same confusing 16-bar form.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=15ju2P7iskQ

But this track also brought me to the bonus track on this album. The bonus material includes an interview of the producer of the track with W.C. Handy himself regarding Louis Armstrong. I was surprised to hear how much Handy emphasis “naturalness.” Handy thought that audiences most liked Louis because he brought a “pride of race” to his playing.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sFlFtRJZHPM

I struggled to understand why Handy valued “naturalness” so highly. Especially when he took samples of black musical culture, polished it, and commercialized it. I think perhaps Handy gave a title to the movement of the Blues, but he soon watched it expand to engulf several different genres and become mainstream popular music. As the consumers enjoyed the folk aspect of the music, Handy tried to make this more of a selling point to his music. He soon began to place a lot of value on Authentic Black American Music, after the fact of Memphis Blues’ initial publication.

So why don’t I think of the Memphis Blues sound as “The Blues?” Well, likely it is due to the influence of Robert Johnson as recorded by the Lomaxes and other influences. This may have led to the B.B. King, Jimi Hendrix, and Eric Clapton sounds that I associate with the blues today. To know for sure I would have to start looking into Robert Johnson’s history.

Nevertheless, Handy should be praised for being the Father of the Blues, even if some of his music feels unauthentic to me. As Wald comments in Escapign Delta,

“to say that the artists who gave the music its name and established it as a familiar genre are not “real” blues artists because they do not fit later folkloric or musicological standards is flying in the face of history and common sense” (7).

Wald highlights an important point. Handy certainly put a lot of work into the genre, and he should be remembered for that.

Works Cited

Handy, W., & Bontemps, A. (1957). Father of the blues : An autobiography. London: Sidgwick and Jackson.

Handy, W., & Handy’s Memphis Blues Band. (1994). W.C. Handy’s Memphis Blues Band.

Willie Bunk Johnson/ Lu Watters’ Yerba Buena Jazz Band: Bunk & Lu [Streaming Audio]. (1990). Good Time Jazz. (1990). Retrieved October 10, 2017, from Music Online: Jazz Music Library.

Whitney, S.H. (1914, September 26). “W.C. Handy, Composter of the Memphis Blues, the Man Who is Making Memphis Famous.” Freeman, pp. 6. Retrieved from newsbank.com.