Louis Armstrong playing for his wife in front of the pyramids of Giza, 1961

Louis Armstrong was truly a cross-generational talent. Even today, Armstrong is one of the few household names in the jazz industry. Known as a pioneer of jazz, he was famous all over the world during the peak of his fame, even during some of the most conflicting times in the 20th century. He first grew in popularity in the 1920s with his Hot Five and Hot Seven recordings, afterward continuing as a soloist, a band leader, and even acting in movies. Armstrong was instrumental in the introduction of the swing band era into the jazz and popular music scene.

Because of his worldwide success, Armstrong was asked to go on tours as an ambassador for the United States with his band known as the “All-Stars.” Armstrong was one of many ambassadors who were asked to travel across the world by the US government, as the US wanted to use these jazz musicians to raise its public perception after it had been hurt by the Soviet Union during the Cold War. Other musicians who went on these ambassador tours include Dizzy Gillespie, Benny Goodman, Duke Ellington, Dave Brubeck, and more.

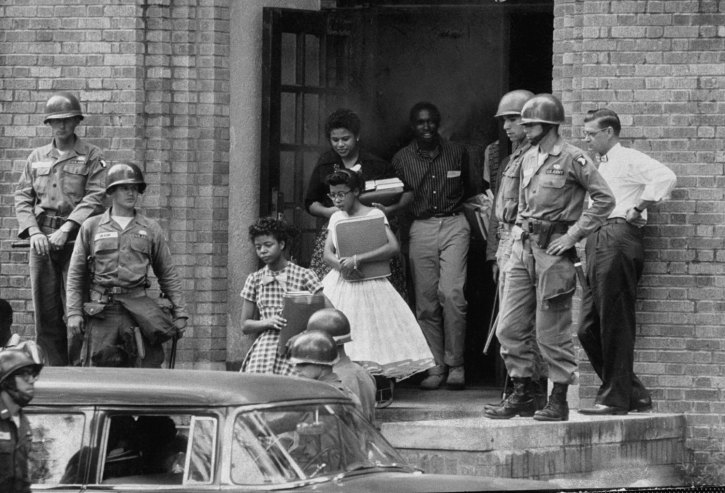

As part of these ambassador tours, Armstrong was asked to visit the Soviet Union in 1957. He originally planned to go on this tour, but after the National Guard refused entry to the 9 black students in Little Rock, Armstrong backed out of the tour in protest of the United States government. After he canceled the tour, Armstrong went on record to condemn the US government for their actions. These statements were recounted by Larry Lubenow, the journalist who broke the story 50 years ago.

“Well, he said that as far as he was concerned, Ike and the government could go to hell. And he sang his version of the ‘Star-Spangled Banner’ to me with very dirty lyrics – oh, say can you mothers – M-F – see by the M-F early light? He was very mad,”

These comments made the front papers of newspapers all over the country and were very significant to Armstrong’s career. For the majority of his career, he had been considered a sellout and an “Uncle Tom” by many of his black peers. He would often remain silent on racial and social issues, and many also believed that he played a “white-washed” form of jazz to appeal to his audiences. Many musicians, such as Miles Davis, even compared his performances to minstrelsy.

Many believe that Armstrong speaking out was the final straw that pushed Eisenhower to make a federal order allowing the students to enter Little Rock’s school. I believe that Louis Armstrong using his power to cancel his tour shows just how powerful individual voices can be. Although he was just one man who rarely involved himself in politics, he still was a driving force in the effort to desegregate schools.

“Remembering Louis Armstrong’s Little Rock Protest.” NPR, NPR, 22 Sept. 2007, www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=14620516#:~:text=In%20September%201957%2C%20Louis%20Armstrong%20cancelled%20his%20tour%20of%20the,integrate%20Central%20High%20School%20there.

“Louis Armstrong in Egypt.” The American Mosaic: The African American Experience, ABC-CLIO, 2024, africanamerican2.abc-clio.com/Search/Display/1463453. Accessed 17 Dec. 2024

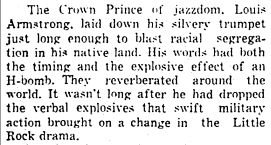

Armstrong was furious at the discrimination faced by the Little Rock Nine and did not hold back. In what was described as having the “explosive effect of an H-bomb”

Armstrong was furious at the discrimination faced by the Little Rock Nine and did not hold back. In what was described as having the “explosive effect of an H-bomb”