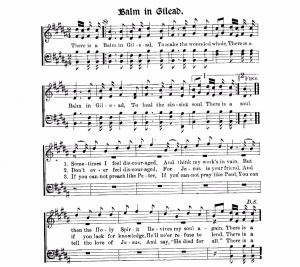

The traditional lyrics and melody. Burleigh, H.T. “Go Down, Moses (Let My People Go!),” in Negro Spirituals (New York: G. Ricordi, 1917),https://library.duke.edu/dig italcollections/hasm_n0708/.

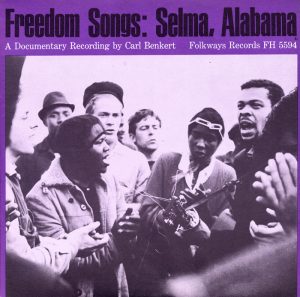

After relentless, long and hard days working in the fields, enslaved black people had little in forms of comfort. Singing spirituals was one way for enslaved people to come together, to sing about their hardships, to praise God, and to lift their spirits. Although some scholars, such as George Pullen Jackson,1 have argued that spirituals stem directly from white Protestant music, spiritual songs centered on Moses and the Israelites’ escape from Egyptian slavery, such as “Go Down, Moses”, highlight how the slave experience distinctly shaped African American spirituals.

In the numerous songs featuring the biblical character of Moses, “Go Down, Moses” is the most popular. This as well as other Moses songs directly reflects enslaved people’s longing for freedom. For many enslaved people, Moses was representative of the brave “conductors” of the Underground Railroad, such as Harriet Tubman, that guided enslaved people to freedom.2 The lyrics of “Go Down Moses” indicating that Moses, someone who did not have as much power as the Pharaoh, could defy him and demand “to let [his] people go!” was incredibly powerful for enslaved people who dreamed of defying their master. In many ways it became a way of defying their master even if they did not run away.3

Although this version of “Go Down Moses” remains the most popular, other versions also highlight connections between the African-American slaves and the Israelites. In John Davis’s version of “Go Down, Moses”, he reveals that the chariot symbolizes the Underground Railroad and the “rivers rolling” as the rivers that runaway slaves would cross though to lose their scent.4 Although the lyrics are different, the message remains the same: a dream and a reflection on the fight for freedom.

Krehbiel’s assertion that “Nowhere save on the plantations of the south could the emotional life which is essential to the development of true folksong be developed”5 rings true in “Go Down, Moses”. Although whites may have shared Christianity with enslaved blacks, they could not emote the same connection with the enslaved Israelites. The emotion present in the slow, melancholy song in the video and sheet music above reveals the deep sadness of living in slavery and a longing for freedom that only enslaved people could understand.

1 Jackson, George Pullen. “Negro-Borrowed Tunes are Traced Back to Britain: Did the Black Man Compose Religious Songs?,” in White and Negro Spirituals, Their Life Span and Kinship: Tracing 200 Years of Untrammeled Song Making and Singing Among Our Country Folk, (New York: J.J. Augustin, 1943): 264-289.