John Poppy, “The South’s War Against Negro Votes” in Look vol. 27, no. 10. May 21, 1963, http://content.wisconsinhistory.org/cdm/ref/collection/p15932coll2/id/5401, accessed April 29, 2018.

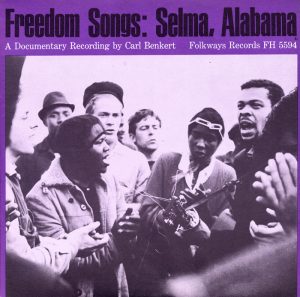

Discouraged by the violence and disappointment, a 21-year-old woman sings with tears in her eyes. She sings of the horrors she has witnessed. She sings of the friends and leaders she has lost. She sings of her hopes for the future. Bertha Gober’s singing of “We’ll Never Turn Back” in the Student Non-violent Coordinating Committee Atlanta field office exemplifies the struggle and dedication of the fieldworkers trying to register black voters in the Deep South. Furthermore, the news article featuring the description of her performance works to gain the sympathies of readers.

John Poppy opens his article with the emotional scene of Gober singing. He uses her singing to usher in his discussion of the hardships and barriers, such as violence and withdrawal of aid, which fieldworkers and anyone who talks to them face in the Deep South. Poppy then inserts the question: “Why does Bertha Gober sing, ‘We’ve had to walk all by ourselves’”.1 He uses this lyric to emphasize the fieldworkers’ demand and need for federal intervention and their frustration that they have not received help at this point.

As an article published in Look, a popular magazine covering anything from sports and fashion to “social issues such as the Civil Rights Movement and women’s changing roles,”2

it had the power to reach people across the United States. The use of music in the article demonstrates how SNCC and their demonstrators utilized music as a tool of propaganda. Poppy illustrates the students’ determination and passion through describing a young woman’s performance of a freedom song. The poignant account of Gober singing “We’ll Never Turn Back” and working alongside her fellow young volunteers to gain equality, worked to gain the sympathies of readers, shifting popular opinion and eventually forcing the federal government to intervene.

1John Poppy, “The South’s War Against Negro Votes” in Look vol. 27, no. 10. May 21, 1963, http://content.wisconsinhistory.org/cdm/ref/collection/p15932coll2/id/5401, accessed April 29, 2018.

2 Library of Congress, “About This Collection,” Look Collection, https://www.loc.gov/collections/look-magazine/about-this-collection/, accessed April 30, 2018.