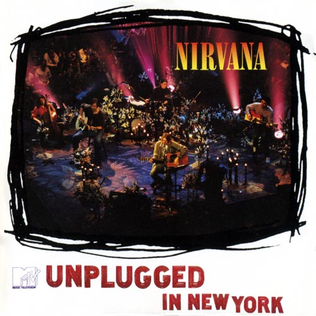

As a “wannabe” angsty, young 8th grade student, “MTV Unplugged in New York” by Nirvana was naturally one of my all time favorite albums. Whether it was the infectious bassline of “Come As You Are,” the absurdity of “Dumb,” or the haunting string arrangements found throughout “Man Who Sold the World,” each track managed to capture the various heartthrobs of a fourteen year old; but none hit me quite as hard as the show’s closing piece, “Where Did You Sleep At Night.” The song encapsulates a vague description of deceit, murder, and sorrow which is inspired and rooted in the 1944 recording by the equally soulful and troubled Huddie “Leadbelly” Ledbetter, a virtuosic 12-string blues and folk guitar player.

While there have been an endless supply of covers and renditions of this folk tune by artists of notable merit (including Dolly Parton, Pete Seeger, Joan Baez, and Chet Atkins), few have managed to achieve the emotional integrity and commercial success of Leadbelly and Nirvana’s recording, and I believe that, through the core elements of “folk” music, and the personal backgrounds of the artists, a connection can be made between the two interpretations.

NIRVANA: https://youtu.be/iUSW7dYZM9w

LEADBELLY: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PsfcUZBMSSg

From the work of the Lomax family to the later tunes of Bob Dylan, folk songs have transformed from a collection of songs that define a culture or generation to the production of individual songs that center around the sentiments and reactions of the performer. Both Nirvana’s 1994 and Leadbelly’s 1944 recording of “Where Did You Sleep At Night” embody the latter of the stages. Using a lyrically simplified version of the original tune, “In the Pines,” which dates back to the 1870’s Southern Appalachian region, Cobain and Ledbetter achieve impassive recording style that is rooted not in the story, but in the personal and stony mood behind the piece. While Leadbelly employs a simple acoustic guitar accompaniment, deadpan call-and-response, and free, vibrato filled vocals, Cobain implements a sparse, electric guitar-string arrangement, dry, hoarse vocals, and stark cadences that reach a similar aura of sheer misery and suffering. By delivering personal and unique renditions of the same folk tune, Leadbelly and Cobain successfully open themselves up to any and all listeners, accessing the bare human connection that lies at the heart of the American folk movement.

Additionally, in a musical genre that often undergoes revivalist movements, artists must consistently be able to deliver unique and intimate takes on “traditional folk tunes.” When analyzing the personal backgrounds of Leadbelly and Cobain, parallels can be drawn that inevitably contribute to their passionate and distinctive performances. Cobain, who lived a tragic life of depression and severe drug abuse, had consistent run-ins with the law, while Leadbelly was incarcerated multiple times, pleading guilty for charges of murder and attempted murder. After considering the half-century time gap and cultural differences between the two artists, it would be ridiculous to compare any background information, however, a common coping mechanism exists in both individual accounts: music. After receiving a guitar from his uncle at the age of twelve, Cobain used music throughout his life to combat and express himself through any personal, family, and drug related obstacles. Similarly, Leadbelly used music as a means to escape and assert his redefined self after years spent in various prisons. In a 1954 article for the Chicago Defender, Langston Hughes summarizes Leadbelly’s musical journey.

“Well, I guess you know there was once a singer named Leadbelly, and he was a penitentiary boy, and he sang his way free. I guess you know he got locked up again, but he got out singing. And he sang songs from here to yonder. He sang himself great. He sang himself famous.”

Through these mental and life altering difficulties, Leadbelly and Cobain both created profound and unique music that inspired and touched the hearts of their respective audiences. One only needs to go as far as a Southern Appalachian tune such as “Where Did You Sleep Last Night” to see the emotional core that connects an entire community in a folk-based tradition.

SOURCES

Bibek Acharya. “Where did you sleep last night-Nirvana-MTV unplugged.” Youtube. Dec. 11, 2016. Accessed October 16, 2017. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iUSW7dYZM9w

“Kurt Cobain.” Biography.com. April 28, 2017. Accessed October 16, 2017. https://www.biography.com/people/kurt-cobain-9542179.

Hughes, L. (1954, Sep 04). Slavery and leadbelly are gone, but the old songs go singing on. The Chicago Defender (National Edition) (1921-1967) Retrieved from https://search-proquest-com.ezproxy.stolaf.edu/docview/492889401?accountid=351

Sessionsinthedesert. “Leadbelly – house of the rising sun.” YouTube. March 08, 2008. Accessed October 16, 2017. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=y5tOpyipNJs.

Weisbard;, Eric. “A Simple Song That Lives Beyond Time.” The New York Times. November 12, 1994. Accessed October 16, 2017. http://www.nytimes.com/1994/11/13/arts/pop-music-a-simple-song-that-lives-beyond-time.html?pagewanted=all.

This is excellent work: not only did you uncover a great primary source (Langston Hughes on Leadbelly! I’m glad to know that exists!) but you wrote an insightful post about something that matters to you and to lots of other people (including your professor). Your insight that folk music shifted in the 20th century to include both community-oriented music (the old model) and individually expressive music whose meaning depends on the performer (the new, Cobain and Leadbelly model) is a really clever one. It helps explain why when we say “folk music” today we often think of Dylan, Baez, Seeger, and even Leadbelly first, rather than Sacred Harp singing or nursery rhymes.

You’ve got me thinking in brand new ways about stuff I’ve been teaching for a long time – thank you!