How did students get their news in the 1960s? The Manitou Messenger was the main source, but events were also broadcast through KSTO, the radio station which went through several ups and downs in the past 60 years, and which now occupies the 93.1 air wave. Acting as KSTO’s assistant manager has led to my interest in the station’s history. What were the goals of the original staff, and what kind of music was broadcast? Putting together a more comprehensive history than our blog’s page is something I’ve wanted to do for a while, and the Manitou Messenger seemed like a logical and reliable source. I tracked the first few years of KSTO’s history through Mess articles, and surprisingly, I found more information about the station’s managerial past than the musical catalogue. Ultimately, I found that the music and news came from the hill more than the Great Beyond. But still, culture and drama ensue! Read all about it:

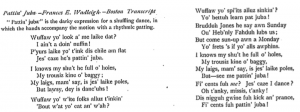

KSTO’s official “History” page states that the station began broadcasting in 1957, beginning each day with “Fram! Fram! St. Olaf” and ending with “A Mighty Fortress.” The Mess began its coverage of KSTO in 1959, writing about the grand reopening of the station (songs played during the first day included selections by the Kingston Trio, the St. Olaf Choir, and “a smattering of mood music interspersed with Broadway show hits”). The paper reported that “Plans…provide for regular news broadcastings which will include information of scheduled Hill activities and side lights.”

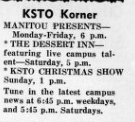

Early broadcasts kept students posted on campus activities, but “music of the type conducive to study” was played during evenings from 6-10 pm. The radio station occasionally advertised their events in a small box entitled the “KSTO Korner” (this only stuck around for a few years, maybe due to the unfortunate name that can only be attributed to the happy-go-lucky, “gee whiz!” tone of the 50s-era Mess). What we learn, however, is that KSTO supported live campus talent through its show “The Dessert Inn”–we can only assume that some of the campus talent involved music.

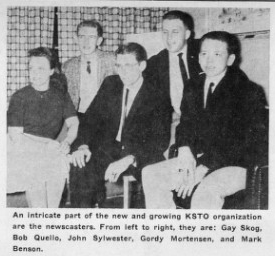

KSTO underwent more changes in the early 1960s, installing a Current Carrier system that connected the station to the student dorms. Reports from the 60s are pretty sparing, although KSTO’s history page notes that the station had a weekly publication of top ten hits at the time. Large events in KSTO’s history–most notably a fire in 1970 that destroyed $3,000 worth of equipment–went unreported, but we know that debates and school sporting events were broadcast across campus.

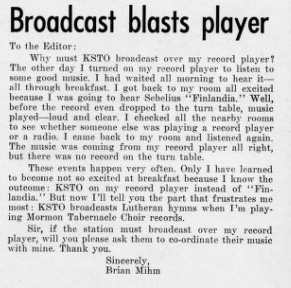

KSTO has evolved significantly from its 1959 iteration, but there are still some similarities between the new and old station. There were budget proposals (despite the fact that the 1960 request of $125 is a far cry from our current budget), shows with student discussions, and a regular programming schedule. Interestingly enough, some of our current goals for the station–more campus involvement, a bigger focus on news, and field reporting from live events–resemble the focus back in the day. And luckily for us, the station’s connection with the Manitou Messenger is stronger now, with the paper reporting on upcoming concerts and publishing the station’s schedule every semester. We’d like to continue that partnership–even though we could potentially nix the impassioned editorials.

Sources:

“History.” KSTO 93.1 FM. Accessed April 20, 2015. https://pages.stolaf.edu/ksto/about-ksto/history/.

“Thursday Night Marks Grand Opening; Return of KSTO Station to Campus Radio.” Manitou Messenger, May 1, 1959. Accessed April 20, 2015. https://contentdm.stolaf.edu/cdm4/document.php?CISOROOT=/mess&CISOPTR=12656&REC=3.