I took an interest in “patting juba,” a form of music-making created by African Americans in the 19th century, because of the patterns, the musicality, and the songs that accompanied it. There is little information on the specific type of dance, however, and the first primary source I encountered was a racist “example” of a juba text penned by a Boston-based writer. Juba has finally gained the appreciation of historians and musicians as viable folk music, but the dance form’s history serves as a reminder of that music as a way to stereotype African American traditions.

Juba came from dances in Africa (where it was called Giouba) and Haiti (known as Djouba). Another name for the dance is Hambone. This name, which also has origins in slavery, supposedly originated from “hand-bone,” the hard part of the hand that makes the most sound.

Juba is characterized by complicated patterns (they generally involve 3-over-4 rhythms), now-obscure steps like the ‘turkey trot’ and ‘pigeon step,’ and corresponding rhymes. Arguably, the most well-known rhyme, used by juba and hambone performers alike, is called “Juba Juba:”

Juba dis and Juba dat,

and Juba killed da yellow cat,

You sift the meal and ya gimme the husk,

you bake the bread and ya gimme the crust,

you eat the meat and ya gimme the skin,

and that’s the way,

my mama’s troubles begin.

There are numerous variations to the lyrics, but the first two lines nearly always remain the same. Danny “Slapjazz” Barber explains the meaning as part of an apprenticeship project in Figure 1. He begins talking about the song at 2:02, continuing on to describe its history.

Figure 1

As was the case with slave songs, many spectators didn’t accurately record juba steps, often deeming the dances wild and immoral, or forgoing descriptions by stating that the movements were beyond words. It wasn’t until minstrel shows in the mid-1800s that juba became known to a larger white audience. Minstrelsy’s appropriated juba has a complicated relationship with the dance and its origins. Scholar Andrew Womack notes that minstrel shows hugely influenced American culture, and that the characters presented were dimensional, albeit offensive and highly stereotyped. One such character was Master Juba, played by free-born African American William Henry Lane. Lane’s character is easily one of the most recognizable personas in minstrel history, and the surname quickly evolved into a stock title for black characters. Traveling with an otherwise all-white cast, Lane performed his dance, described as a combination of juba and a jig, in America as well as Europe. He was seen as a novelty, but observers were nevertheless impressed by his skill. As The Manchester Examiner wrote:

“Surely he cannot be flesh and blood, but some special substance, or how could he turn and twine, and twist, and twirl, and hop, and jump, and kick and throw his feet with such velocity that one think they are playing hide-and seek with a flash of lightning!”

Figure 2: William Henry Lane

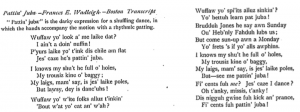

On the other hand, white writers commonly used juba as another opportunity for stereotyping African American dialect. In Figure 3, Frances E. Wadleigh uses slurs, an overexaggerated dialect, and offensive caricatures to showcase the “current literature” of black music.

Figure 3

In spite (or, in some cases, because) of the appropriations, juba has remained in mainstream culture. Variations of the beats and rhythms have made their way into modern music, most notably in Bo Diddley’s song, “Bo Diddley’s Beat.” Hambone has been preserved and taught as a black folk melody, particularly in the south, and the dance steps are widely seen as a precursor to the jitterbug. Though juba was used as a vehicle for stereotypes, the dance and music have become an important part of American culture, and another example of how influential the songs–both original and appropriated–have become.

Footnotes

Crawford, Richard. “”Make a Noise!”: Slave Songs and Other Black Music to the 1880s.” In America’s Musical Life: A History, 409-410. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2007.

Wadleigh, Frances E. “Pattom’s Juba.” Current Literature V, no. 1 (1890): 70. Accessed February 21, 2015. http://search.proquest.com/americanperiodicals/docview/124834707/797372C1C4314861PQ/1?accountid=351.

Welch, David Cranstoun. “Shave and a Haircut: Two Bits.” Perfect Sound Forever. August 1, 2008. Accessed February 19, 2015.

Womack, Andrew. “Ridicule and Wonder: The Beginnings of Minstrelsy in New York.” In Afro-Americans in New York Life & History, 94-95. 2nd ed. Vol. 36. Buffalo: Afro-Americans in New York Life & History.

Great post, Haley! I meant to bring up in class a link that I thought of between patting juba and contemporary African American culture, but I never did, so I thought your post would be a good place to do so! That link is stepping. I’m not sure how wide spread step teams are, but my high school in Atlanta had a step team that performed body percussion routines that seem similar to descriptions of juba. I did a little bit of investigation and found this book on google that confirms that link:

https://books.google.com/books?id=PsVA9GTexK4C&pg=PA81&lpg=PA81&dq=stepping+and+juba&source=bl&ots=Ou3IsAH_NR&sig=4rkvL93HROVLjfWs-W_BMJgaEmg&hl=en&sa=X&ei=LDAGVY3lE6HfsASj8ICoAQ&ved=0CCQQ6AEwAQ#v=onepage&q=stepping%20and%20juba&f=false

Stepping does have strong connections to drill teams as well, so I don’t think we can consider it a direct preservation of juba, but it is a lot more tied to African American tradition than the appropriations of juba in minstrel shows that you mentioned. So, I guess what I’m saying is–like you mentioned with Bo Diddley and Hambone preservation–it is always nice to learn about ways that juba was preserved (and is still practiced) by African Americans and not just appropriated by people outside of the tradition.

H, you do a great job of balancing your gratitude for the few historical sources we have that document the juba tradition with your disappointment in the clear bias and likely unreliability of those sources. I’m curious to know how you think juba should be preserved in our era: should composers (like yourself) incorporate it into new music? Should it be passed down orally, generation to generation, like Danny Barber is doing?

Two minor details to correct: You quote The Manchester Examiner (which you should italicize) in your text, but there’s no citation in the endnotes. And it’s not clear why you cite David Welch’s article on “Shave and a Haircut,” nor is it clear that the source is a website rather than a database or a book. I know we’re still figuring out how we want to cite things in these posts, but I’d say our biggest priority has to be helping readers re-discover the sources we’re pulling together to support our discussion.

All in all, though, this is extremely well written and thoughtful. Keep up the good work!