In 1939, John Lomax and his wife Ruby Terrill Lomax set out on an adventure into the homes and communities of the American South to collect folk music. Their trip documented music that had developed in the American South and stood as a symbol of southern rural white culture. Their collection of recordings includes the American classic “Turkey in the Straw” performed by Elmo Newcomer and his son Theo Newcomer, available below. 1The song represents the simplicity of the “down home” feeling represented in folk music.

Like much folk and country music, “Turkey in the Straw” features both the banjo and the fiddle. Although folk and country music are often considered white genres , the presence of the banjo indicates the influence of the African American community, as the banjo has African origins.2 In addition to standing as a representative of traditional Southern music, the song features the duple meter and 16-bar units popular to bluegrass music These features indicate how this song and others like it influenced later Southern and Appalachian Mountain music.

“Members of the Bog Trotters Band, posed holding their instruments, Galax, Va. Back row: Uncle Alex Dunford, fiddle; Fields Ward, guitar; Wade Ward, banjo. Front row: Crockett Ward, fiddle; Doc Davis, autoharp” in Lomax Collection (Galax, Virginia: 1937 )http://www.loc. gov/pictures/collection/lomax/item/2007660127/ (accessed February 25, 2018).

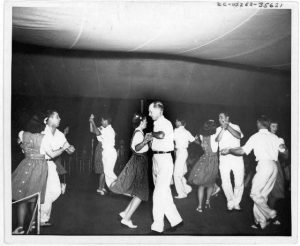

“Bent Creek Ranch Square Dance Team dancing at the Mountain Music Festival, Asheville, North Carolina” in Lomax Collection (Asheville, North Carolina: 1938-1950) http://www.loc.gov/pictures/ colle ction/lomax/item/2007660059/ (accessed February 26, 2018).

This recording, performed in the Newcomers’ home, demonstrates how folk music was part of the lives of the poor rural family and the community. The lyrics in the Newcomers’ performance, “Went out to milk/ And I didn’t know how/ I milked the goat/ Instead of the cow” reflect the everyday lives of rural white farm families.

In addition to being performed in their homes, the themes of this classic song related to the rural farm community at large. White rural Southerners shared this music at gatherings and this song like many other folk songs were popular square dancing tunes. Square dancing has been a tradition in the Appalachian Mountains since the 19th century.4 One place that folk music and square dancing came together is at the Mountain Music Festival in North Carolina. This gathering and the general union of folk music such as “Turkey in the Straw” and square dancing celebrates folk music and the “down home”, simple lives of the rural white communities.

As we discussed in class, this song like many other folk and country songs gave rural Southern whites a voice, art, and setting to express their culture. This often came at the expense of the black community who were excluded from the memory of folk music by the music industry and scholars such as John Lomax.

1 Newcomer, Elmo and Bill Newcomer, “Turkey in the Straw” in John and Ruby Lomax 1939 Southern States Recording Trip (Pike Creek, Texas: 1939) http://www.loc.gov/item/lomaxbib00159/ (accessed February 25, 2018).

2Allen, Ray. “Folk Musical Traditions” in Encyclopedia of American Studies, edited by Simon J. Bronner (Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press, 2017) http://eas-ref.press.jhu.edu/view?aid=650&from=search&query=square%20dance&link=search%3Freturn%3D1%26query%2520dance%26section%3Ddocument%26doctype%3Dall (accessed February 26, 2018).