As I was searching for sources to write about this week, I stumbled upon “The Appeal,” which was a moderately successful African-American Newspaper for nearly four decades until 1923, based out of St. Paul, Minnesota. African-American Newspapers were newspapers published specifically for black communities in the 19th and 20th centuries. At the time “The Appeal” was founded, there were only around 1500 black people in the twin-cities area.1 Because of this, “The Appeal” was targeted to a much larger demographic than just black residents in Minnesota, and became popular throughout the country.

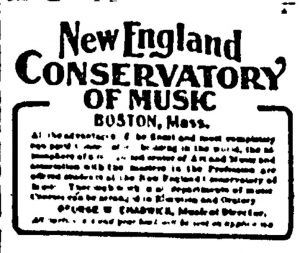

While I was searching for music related topics within “The Appeal,” I noticed something interesting. By 1906, the New England Conservatory had started advertising in nearly every issue of “The Appeal.”2 This suggests that by 1906 at the latest, the New England Conservatory was seeking out black students to study music on the east coast. This is particularly notable given that many colleges wouldn’t even enroll black students until much later in the 20th century. St. Olaf’s first black graduate was in 1935, Princeton’s was in 1947, and University of Alabama’s wasn’t until 1965. The New England Conservatory’s first black graduate was Rachel M. Washington, who graduated in 1872, just five years after the conservatory was founded.3 Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s wife Coretta Scott King was also a graduate of the New England Conservatory much more recently in history.

“Popular Composers. Young Afre-Americans Who Have Attained Great Successes with Songs” – The Appeal

Another article from “The Appeal” highlights the work of Bob Cole and the Johnson Brothers.4 Rosamond Johnson also graduated from the New England Conservatory, while his brother James was a graduate of Atlanta University and a recipient of a doctorate from Colombia according to “The Appeal.” James wrote the lyrics and Rosamond composed the music of “Lift Every Voice and Sing,” which is known today as the “Black National Anthem.”

Bob Cole partnered with the Johsnon brothers to create their own vaudeville act. Their entertaining pop music is the focus of a column in “The Appeal.” Cole and the Johsnon Brothers took advantage of a society that was obsessed with Minstrelsy and black entertainment, and produced music that fought against the pejorative and negative stereotypes usually portrayed in the genre. All three men were early civil rights activists, and they used music to express their views in a way that white audiences wanted to engage with.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, there were not many opportunities for black people to achieve upward social mobility in the white-supremacist framework of the United States. However, with minstrelsy and black music in such high demand, many black people were able to use music to gain an education, a livelihood, and further their political messages. In the years immediately after the reconstruction, music was a driving factor towards equality for black people in America.