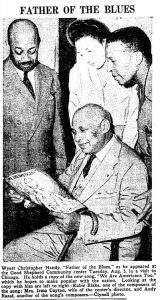

The Chicago Defender, established in 1905 by Robert Abbot, is celebrated as one of the most influential Black newspapers.1 An article written by Diana Briggs and published in the Defender on August 16, 1941 features Wyatt Christopher, or W.C. Handy. Handy played a significant role in the popularization of the blues in the early 20th century.2 In the concise article, Briggs hails him as the “Father of the Blues,” and tells of his visit to the Good Shepherd Community Center.3

W.C. Handy at the Good Shepherd Community Center7

The article tells of Handy’s relationship with the blues and opinions on other related genres, such as Swing.4 Briggs openly presents Handy’s strong, uncompromising stance on the Swing style. Handy categorizes Swing as a “prostituted melody of the blues,” used for the purposes of economic piracy on the behalf of whites who profit off of it.5 Handy describes Swing in an extremely decisive manner, calling it an aborted form of blues.6

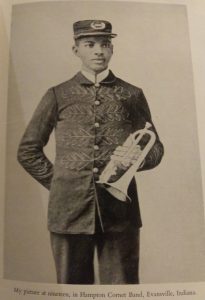

When considering Handy’s career as a musician, composer, and bandleader, his almost graphic portrayal of swing seems entirely appropriate. Handy’s take on Swing relates to the greater, “message for his race” that Briggs notes throughout the article.8 The information surrounding Handy’s protective attitude towards blues in this article complements his career, which he spent, “making the blues a consciously composed art,” and bringing Black music into the mainstream of public culture.9 As a pioneering artist of the genre who believed that blues, “shall help [the] Negro in the fight for equal rights,” W.C. Handy’s unwavering take on both the importance of blues and the problems of Swing become unquestionable.10

1 Pride, Karen E. “Chicago Defender Celebrates 100 Years in Business.” Chicago Defender, May 5, 2005. https://web.archive.org/web/20051201092230/http://www.chicagodefender.com/page/local.cfm?ArticleID=687.

2 Evans, Dylan. “Handy, W(illiam) C(hristopher).” Grove Music Online, January 20, 2001. https://doi.org/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.12322.

3 Briggs, Diana. “Chicago Hails W. C. Handy, Father of the Blues: Father of Blues Greets Chicago with Message for Race and Music FATHER OF THE BLUES.” The Chicago Defender (National Edition) (1921-1967), Aug 16, 1941. https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/chicago-hails-w-c-handy-father-blues/docview/492581628/se-2.