After the American Civil War, over 25,000 new pianos a year were sold in America and by 1887, over 500,000 people were now studying piano. As a result, the demand for sheet music grew rapidly and more and more publishers began to enter the market [1]. Though it may be more pleasant to believe that these publishers printed music simply to share the beauty of music with the world, this was not usually the case. Publisher’s main purpose was to make money, and they did this by printing music that would sell. Minstrelsy was music that would sell, and a large way publishers caught the consumers eye was through cover art and using blackface to promote these minstrel tunes.

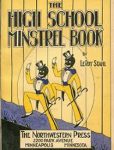

Daniel Foster, of Duke University, believes that “because blackface relied increasingly on the publishing industry and the visual medium of sheet music, it also began to depend more on the eye, and because sheet music assumes a certain level of literacy and luxury, this reliance on the eye encouraged blackface’s growth as a middle-class phenomenon [2].” Foster believes minstrelsy was standardized and ritualized through the publishing industry. Publishing houses began making minstrelsy more accessible, and “some publishing houses even began to carry scripts that amateurs could order for putting on their own minstrel shows [2].”

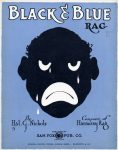

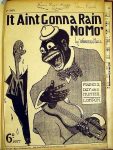

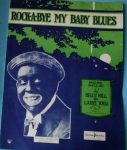

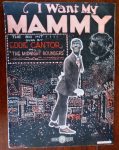

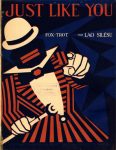

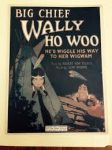

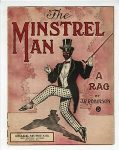

A large amount of minstrel art was required to adorn these pieces of music. Below is just a sample of the large amount of blackface music I found [3][4]. The music is from multiple sources, including the Sheet Music Consortium and Ferris State University’s Jim Crow Museum. I also found a surprising number of this music up for auction on eBay.com.

- courtesy of Sheet Music Consortium

- found on Ebay

- Courtesy of Ferris State University

- found on Ebay

- found on Ebay

- courtesy of Sheet Music Consortium

- Courtesy of Ferris State University

- Portrays Native Americans- publishers did not only mock African Americans

- Found on Ebay

There are several similarities I noticed between the artwork. Most of the covers have a man on the front, either with only the face or with the man dancing in a top hat. The poses that the people are in are not flattering, and look unnatural or unpleasant (especially the ‘It Ain’t Gonna Rain No-Mo.’ piece). The titles use dialect, and mention stereotypical things such as “mammies,” the blues, and rag. I included “Big Chief Wally Ho Woo: he’d wiggle his way to her wigwam,” because I think it is important to note that these publishers were not only marginalizing/exoticising black people, but also Native Americans.

In my research I found it surprising that so many minstrel pieces were for sale on eBay- some songs sell for as much as $75.00. Clearly people are currently interested in buying and selling this music. Despite the changing views on racism and the fact that publishers do not print blackface anymore, consumer culture continues to live on.

Sources:

[1] Reublin, Rick. “In Search of Tin Pan Alley.” The Parlor Songs Association, May 2009.

[2] Foster, Daniel. “Sheet Music Iconography and Music in the History of Transatlantic Minstrelsy.” Duke Press, Mar. 2009.

[3] Courtesy of the Sheet Music Consortium. University of California, Los Angeles.

[4] Courtesy of the Jim Crow Museum. Ferris State University.