I have to admit that although I am Chicanx, I don’t know very much about Chicano music. In general, I haven’t heard much about Chican@ art other than celebrities like Selena. Of course, there was the Chicano movement of the ’60s which I was aware of but what I didn’t know was that there was an entire Chicano Renaissance [1]. In an essay titled, “Chicano Movement Music” from The Latino American Experience, Azcona gives an overview of the music of the Chicano Movement and specifically how higher education was a major part of the movement [1]. College campuses became springboards for Chican@ musicians where bands, as well as solo artists such as Joan Báez, got their start.

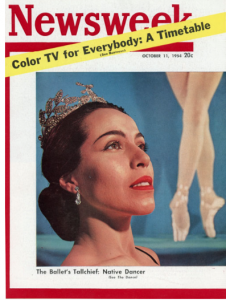

JJ6537 Joan Baez circa 1966

American folk singer Joan Baez sings and plays acoustic guitar on stage during a European tour, East Berlin, Germany.

(Photo by Hulton Getty)

Joan Báez was just this year inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Game along with Tupac Shakur, Pearl Jam, Yes, and Electric Light Orchestra [3]. Her 1974 album, Gracias a la Vida was her first and only full-length album entirely in Spanish. She collaborated with other chican@ music ensembles such as La Rondalla Amerindia where they recorded a huelga or strike song called “No nos moverán” which translates to “They will not move us” [1].

From early in her musical career, she was heavily involved with the civil rights movement and marched alongside MLK from Selma to Montgomery as well as a number of other protests, rallies, marches, and toured colleges to encourage young men to resist the draft [2]. Her music was, overall, regarded as a means to spread the pacifist platform during and well after the civil rights era [2].

What I found particularly intriguing about Báez was that she was the daughter of an elite professor, was educated, and primarily sang at protests. Later in life, she founded Humanitas International, a human rights organization; but later when reviving her singing career she lessened her political activism and shut down the org. The questions I am left with are primarily about how her singing domestically and internationally counted as an action that supported change. It is one thing to sing “We shall overcome” but it is another thing to put forth change, which she did, but eventually put her singing career before her human rights organization. The ambiguity of the morality of her choice is pressing, however, perhaps the net impact of her returning to music and a life of advocacy is more fulfilling as well as influential. I think there is also an assumption that individuals who are associated with a marginalized group must choose the path of advocacy over anything else or be labeled as unauthentic.

Sources Cited

[1] Azcona, Estevan César. “Chicano Movement Music.” In The American Mosaic: The Latino American Experience, ABC-CLIO, 2019. Accessed November 12, 2019. http://latinoamerican2.abc-clio.com/Search/Display/1329550.

[2] Meier, Matt S., Conchita Franco Serri, and Richard A. Garcia. “Joan Báez.” In The American Mosaic: The Latino American Experience, ABC-CLIO, 2019. Accessed November 12, 2019. http://latinoamerican2.abc-clio.com/Search/Display/1332577.

[3] Pulley, Anna. “JOAN BAEZ TO BE INDUCTED INTO ROCK & ROLL HALL OF FAME.” Acoustic Guitar, 03, 2017, 15, https://search.proquest.com/docview/1874317065?accountid=351.