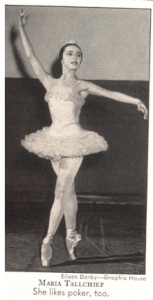

Whilst perusing the “Hearts of Our People” exhibit this summer at the MIA, an exhibit featuring exclusively female Native American artists. What I found striking was a video from the early 1950s of a woman named Maria Tallchief who was in fact not in traditional regalia, but an elaborate ballet costume, pointe shoes, and dancing to Igor Stravinsky. I thought to myself, “Wow, a Native Ballerina? If I would have seen this video as a kid I probably never would have quit ballet.”

The findings of Densmore as well as of the explorer’s accounts we read in class point to a correlation between Native Americans and dance. I would find it safe to say that not all of the dances Densmore recorded, let alone what those who made first contact saw, made it to the 21st century in their original form due. The role of the U.S. government in intentionally trying to vanish Native Americans, leading to the “Vanishing Indian” sentiment which eventually evolved into what Rebekah Kowal refers to as the Termination Era (early-mid 20th century), created the environment out of which Tallchief had her start. The article that caught my eye was titled, “American as Wampum” and was published in TIME magazine in 1951 following her performance with the New York City Ballet Company in Balanchine’s adaption of Firebird [1]. The article claims she was produced by the same era that created Shirley Temple and that:

“Onstage, Maria looks as regal and exotic as a Russian princess; offstage, she is as American as wampum and apple pie.”

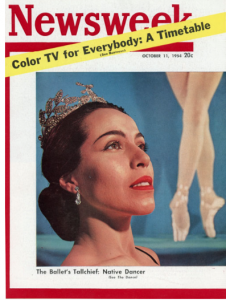

The discussion of her lineage only mentions that her father was a full-blooded member of the Osage tribe [1], further exoticizing her and leaving out the fact that her mother had European heritage: Scotch, Irish, Dutch [2]. It is possible that the author of the article simply didn’t know that Tallchief was mixed-race but I find it more likely that her choice in self-identifying primarily with her Native heritage contributed to her fame and success as the first American Prima Ballerina. Her image, both literal and social, is another aspect of her life I found compelling. It was her front page of Newsweek that crowned her, “the finest American-born ballerina the twentieth century had ever produced…” [2]. The use of a literal crown in both articles, Newsweek and Time, the image of the “Native American Princess”. This brings us back to depictions of the idealized Native woman, the peace bringer such as Pocahontas, a  role model of femininity and what was called civilization, integration, or assimilation[3]. Toll argues that the trope Tallchief embodies is more complicated than simply playing the civilized Indian in that her achievement of being the first-ever American Prima Ballerina, that she was a creator of western culture rather than an “assimilated Princess” [3].

role model of femininity and what was called civilization, integration, or assimilation[3]. Toll argues that the trope Tallchief embodies is more complicated than simply playing the civilized Indian in that her achievement of being the first-ever American Prima Ballerina, that she was a creator of western culture rather than an “assimilated Princess” [3].

Works Cited

[1] “American as Wampum.” TIME Magazine, vol. 57, no. 9, Feb. 1951, p. 78. EBSCOhost, search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=tma&AN=54161559&site=ehost-live.

[2] Kowal, Rebekah J. “‘Indian Ballerinas Toe Up’: Maria Tallchief and Making Ballet ‘American’ in the Tribal Termination Era.” Dance Research Journal, vol. 46, no. 2, 2014, pp. 73–96., doi:10.1017/S0149767714000291.

Toll, Shannon. “Maria Tallchief, (Native) America’s Prima Ballerina: Autobiographies of a Postindian Princess.” Studies in American Indian Literatures, vol. 30, no. 1, 2018, pp. 50–70, https://muse.jhu.edu/article/692228.

“…the trope Tallchief embodies is more complicated” is absolutely right. It’d be interesting to look into whether/how Tallchief talked about her Native identity. Maybe you could get a hold of the autobiography that Shannon Toll seems to refer to? I wonder, because we might also ask whether holding Tallchief up as an exceptional Native American – even without reducing her to a stereotype of the Native American Princess – ignores the extent to which she saw herself as a creator in a (largely French and Russian) tradition distant from Native American practices. You hint at this in your last sentence, but you also contradict it when you suggest that she chose to self-identify as Native (even when she could have passed for non-Native). Like you said: it’s complicated. Let’s keep thinking through this fascinating case together.