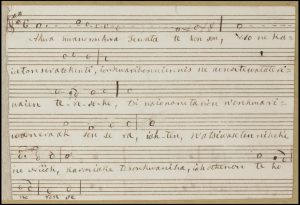

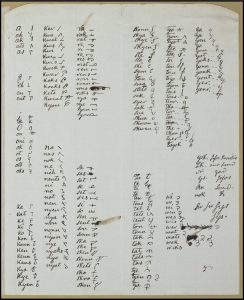

Looking through the papers of Eleazer Williams (1758-1858), I found sheet music written in the Iroquois language. The document was found amongst many other items within a scrapbook (1758-1846), and it most likely came from Williams’ time in New York and Green Bay, Wisconsin, as a missionary to the Oneida Indians.1 When it comes to determining the trustworthiness of this source, one might look to the plausible objectives of Eleazer Williams at the time.

Because the lyrics were written in the Iroquois language, it is possible he wrote down the music purely for his own benefit, rather than with the intentions of educating the white masses. Williams would have had to learn the language as a means to communicate with the American Indians and convert them, as was his mission. This personal endeavour of learning the language is evident by the “Notes on the Iroquois language” within the Papers, 1758-1858. Nevertheless, the objective of missionary work differs from the objectives of explorers and anthropologists/ethnographers, some of whose writings and recordings we have read and heard.

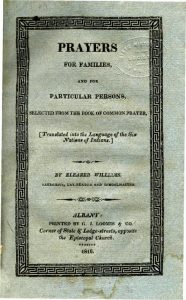

Anthropologists typically lived amongst a people to learn and understand their customs. Their recordings were intended for European readers/listeners, and they were unknowingly biased. It is likely Williams saw the Oneida Indians as ‘Other’ and inferior to himself, as did the European explorers of his time; however, he wrote sermons and translated religious texts into the language of the Oneida. This is evident by his book Prayers for families and for particular persons: selected from the Book of common prayer translated into the language of the Six Nations of Indians (1788-1858), which translates a selection from the Episcopal Book of Common Prayer into Oneida.2 Because of this text, it can be assumed that Williams wrote for foreign ears, and any notes on the foreign language were probably written for his own study. Researchers should take the intended audience into account when determining the trustworthiness of this document, despite any biases that may appear in his papers.

Fagnani, Giuseppe. Eleazer Williams. 1853. Oil on canvas. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC.

Furthermore, what makes Eleazer Williams especially unique in comparison to our previous readings are the facts that he “was of mixed Indian-white parentage”, and “he envisaged an Indian empire west of Lake Michigan under his rule”.3 After hearing the first fact, one could argue his intentions of recording this music on paper could have been to better understand and relate to the culture. However, knowing his true motives were to take control over the people, he is seen in a much more negative light. Granted, wanting to rule over the Oneida Indians doesn’t necessarily mean the music Williams wrote down was inaccurate/inauthentic. Considering the sheet music was found amongst other language materials, it could have been one of his sources for learning the Iroquois language. The scrapbook within which it was archived could have been a collection of Eleazer Williams’ personal mementos. Therefore, it is possible the music he recorded on paper is a trustworthy example of Oneida Indian music.

1 Williams, Eleazar. Papers, 1758-1858. Available through: Adam Matthew, Marlborough, American Indian Histories and Cultures, http://www.aihc.amdigital.co.uk/Documents/Details/Ayer_MS_999.

2 Williams, Eleazer. Prayers for Families and for Particular Persons Selected from the Book of Common Prayer. Albany: Printed by G.J. Loomis and Co, 1816. Available through: Wisconsin Historical Society, Digital Public Library of America, https://dp.la/item/d957d82e178a2376606b7cea19cb06a1?back_uri=https%3A%2F%2Fdp.la%2Fsearch%3Fq%3DWilliams%252C%2BEleazer%26subject%255B%255D%3DNative%2BAmericans%26utf8%3D%25E2%259C%2593&next=2&previous=0.

3 “Williams, Eleazer 1788-1858.” Wisconsin Historical Society. August 3, 2012. www.wisconsinhistory.org/Records/Article/CS1694.

You’re right that it’s tricky to determine the trustworthiness of a source in any case, and so much more in the case of someone like Williams with twisted motives. I wonder if there were other missionaries or wannabe rulers who took the trouble to learn Native languages if only to use their knowledge to convince/trick Native Americans into capitulating rights, land, or their bodies.

On the other hand, as you point out, Williams had no reason to corrupt his sources in transcribing music and text as he did; he wasn’t interested first and foremost in music transcription, nor was he trying to “tame” anyone or erase any cultures. It might be that because he was so focused on other goals, his musical transcriptions are *more* trustworthy than some of the others we’ve seen, at least before the late 19th century.

Really interesting research – keep up the good work!