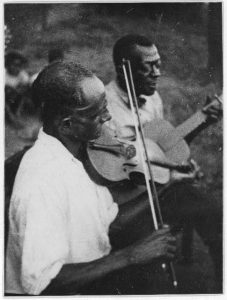

After years of being away, this man in the following picture returns to his family. My first impressions on this picture are sympathy for the family’s experiences. This image gives off a feeling of overwhelming joy, and even a sense of passion among the people in the photo.

The photo resembles what seems to be a free African-American family. This past week, we read about what defines the sound of black or white music. As we dove more into what defines a genre, often times we found that people attach themselves to a particular genre of music due to their ability to relate to the lifestyle experiences of artists playing the music. An example of people relating to music is someone who’s been separated from a loved one listening to music that talks about being separated from a loved one. In the photo, the artist paints a picture of a family experience amongst an African-American family. This theme was common amongst many African-American families who were slowly gaining their freedoms from slavery.

In this second image, the artist portrays a college student laying on their desk, restless, being protested against by plates, pottery and kitchen appliances.

The reason I chose this particular image was that it represents a generational divide. Essentially, the college student is living a lifestyle in which she does not have to work with any plates nor cooking itself; she has temporarily emigrated away from that lifestyle through education. The plates are representative to those people who are misunderstanding of her situation by shouting to her, “Do you know anything about us?” and “Have you any idea what I am?” Like much music born of the South, this image is representative of lifestyles that are misunderstood by an external perspective. Simply put: Unless you have experienced it, you will never understand.

Sources:

Johnson, Charles Howard, “For the benefit of the girl about to graduate,” Library of

Congress (1890), http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2002712165/

Northup, Solomon, “Arrival Home, and First meeting with His Wife and Children,”

Twelve Years a Slave: Narrative of Solomon Northup, a Citizen of New-York,

Kidnapped in Washington City in 1841, and Rescued in 1853. (1853)