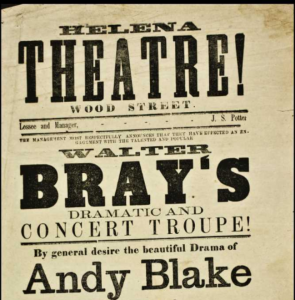

I can freely admit that this playbill announcement caught my attention because I share a name with it. Helena, Montana and its musical and theatrical scene is almost as far from the musical encounters we have discussed between Europeans and coastal Native American tribes as I am, but I do believe that it has some connection to the development of an “American” music.

Native American references are markedly absent from this particular theatre’s presentation, although they seem to have been fairly common in other places at the time. The Montana Territory, not yet a state in 1866 when this playbill was published, was a frontier territory. Clashes between Native American tribes and European settlers were still common. Perhaps this continuing conflict is the reason for this music’s absence; theater is designed to be an escape, and comedy, farce, and melodrama were particularly popular in this period (1). The Vanishing Indian trope doesn’t fit well into the shows of an area that know the Indians have definitely not vanished yet.

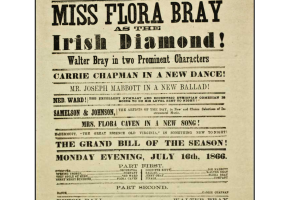

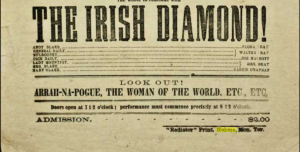

However, there are plenty of interesting features of this program. “Exotic” features or tidbits of a marginalised culture are often used as a draw in entertainment, so it is probable that this is the case here. Prominently displayed are the acts of “Ethiopian” comedian Ned Ward (who would have been a white actor in blackface) and the play “The Irish Diamond.” In discussion of anti-blackness and the racism particularly directed at non-white groups as a society and a class, we often neglect to be aware of the struggles of certain white (as they are considered now, in our black/white dichotomy) ethnic groups, such as the Catholic Irish who were marginalised in both Protestant America and Britain after the English Reformation. This playbill was published not terribly long after a large wave of Irish immigrants came to the United States in the 1840s. This type of wave of immigration often comes with mixed feelings toward the group in question, and the Irish certainly were not met with arms all open. The prominence of an Irish drama in this program could be another example of what was discussed in our very first class session: the construction of a distinct American identity through reference to and use of the art and culture of marginalised American groups, in this case Irish culture and African-American culture through the lens of blackface. There is even a second Irish play in what appears to be a “coming soon to theatres” section at the bottom – Arrah-na-Pogue, which was written in 1864 and adapted into an early silent film in 1911 (2)!

American music and art has always been an amalgamation of cultures, and that of frontier Montana in the 1860s is no different. Home to mostly young, male miners (3), this playbill from a theatre in Helena, Montana nonetheless draws on different styles of music, dance, and theater, and conveys an interesting picture of the artistic landscape that people from this time would have encountered. Much like music of the time, American theater was moving away from its European counterpart and searching for a new identity in the cultural resources of the “New World.”

- Meserve, Walter J. An Outline History of American Drama, New York: Feedback/Prospero, 1994.

- Williams, Henry Llewellyn, and Dion Boucicault. Arrah-Na-Pogue; (Arrah-of-the-Kiss.) or, The Wicklow Wedding. Founded on the Same Incidents as the Celebrated Drama. New York: R.M. De Witt, 1865.

- Wikipedia contributors, “Montana,” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Montana&oldid=915390740 (accessed September 16, 2019).