Many people have a clear and narrow impression of Native American music, broadly amounting to a simple, percussive beat and non-syllabic unison melody atop it. As is the case for many such clear-cut descriptions, this is a gross oversimplification. Through the work of musicologists such as Frances Densmore, we can be secure in the understanding that the music of North America’s native tribes in the 20th century was far more complex than that impression, and assuming that complexity extends both forward and backward through history is natural.

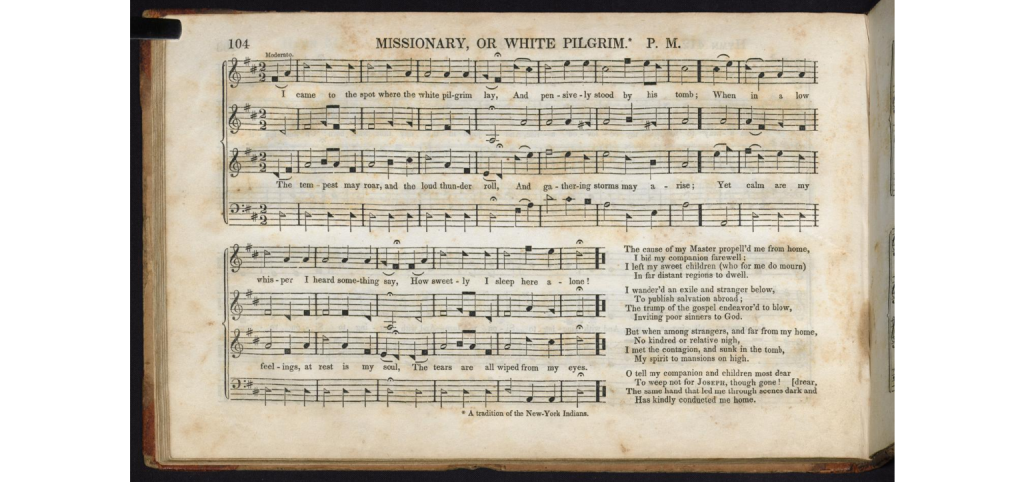

Exemplifying the diversity of Native repertory is a collection of shape-note hymns called Indian Melodies, compiled by Thomas Commuck, a member of the Narrangaset tribe from the East Coast, now living in Wisconsin [1]. The Christian verses, set to choral, sometimes-chromatic textures, are a far cry from the stereotype. Yet its distance raises another concern: that of appropriation.

While Commuck himself professes Christian sentiments–referring to himself as being enlightened “under the blessing of God” and expressing a desire to “spread the knowledge of the Redeemer”–it is informative that his work be titled as it is. The combination of traditional tunes with Protestant verse is seen by the author as an expansion of Indian repertoire in a collaborative, rather than parasitic, light. But that is still not enough to pick apart the dialogues surrounding this work. In the preface, Commuck makes his intentions with the writing clear.

“[The author] feels willing to acknowledge frankly and openly the truth, and he assures his friends and the public, that notwithstanding all other ends which may result from the publication of this work, his object is to make a little money.”

This statement opens up the possibility for concessions made in the interest of financial sustenance. Perhaps, as James Page suggests [2], Thomas Hastings’ involvement in arranging the music was forced by the publisher, thereby obscuring the intended blending of worlds with the one-sided use of the Native as a touchstone for American identity, thereby contributing to the story of the Vanishing Indian. If Commuck was desperate enough for the publishing of the book, it is at least plausible.

However, as a refutation of this line of thought, Commuck’s parting words in the preface emphasize the merely ceremonial usage of the Indian elements of the work. After stating that the tunes will use Native titles, he insists that “This has been done merely as a tribute of respect . . . also as a mark of courtesy.”

If these final words can be taken as genuine (without financial concern forcing his hand), Commuck himself may have been a participant in the era of the Vanishing Indian, at least in part. Referring to the elements of Native American culture which inform the work in such brief terms suggests their non-importance. At the same time, the most apparent part of the book remains the most potent proof of its expansion, rather than narrowing, of Indian culture–its title. Protestant hymns may also be Indian tunes after all.

References

- Thomas Commuck, Indian Melodies, (New York, Lane & Tippett, 1845). Accessed at https://acdc.amherst.edu/view/asc:479052/asc:479130

- James Philip Page, “Thomas Commuck And His Indian Melodies, Wisconsin’s Shape-Note Tunebook”, (1989). Accessed at https://brothertowncitizen.com/thomas-commuck-and-his-indian-melodies-wisconsins-shape-note-tunebook/

This is an excellent post! You’ve uncovered a form of Native American music that I didn’t know existed, but I’m certainly glad to know about them. I wonder if any scholars other than James Page have written about this phenomenon? In any case, it’s a great example of the complexities of the United States’ hybrid sources of musical identity. As I mentioned in class, I’m also glad to see you attend to a form of Native American musicking that doesn’t neatly align with the reductive stereotypes normally associated with Native music. Keep up the good work!