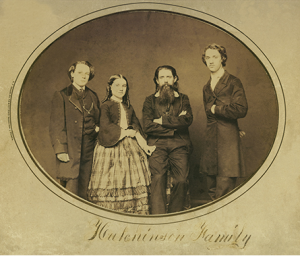

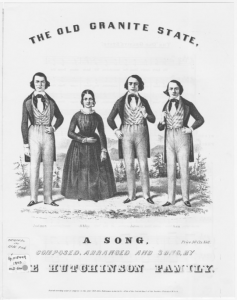

When I set out to write this post, it was supposed to be about a review of the Hutchinson Family Singers that was printed in an abolitionist newspaper in Boston on December 30th, 1842. While exploring that issue of the newspaper, however, I discovered a reprinting of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s poem “The Slave Singing at Midnight.”1 The poem is such a good example of some of the issues we discussed in class earlier this semester that I could not pass it by.

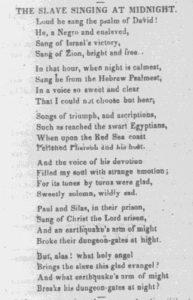

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s “The Slave Sings at Midnight,” as published in the Boston newspaper the Liberator in 1842.

From the first line, “Loud he sang the psalm of David,” Longfellow establishes that the music of slaves was Christian. He repeats these Old Testament themes throughout the poem, likening African slaves to the Israelites fleeing Egypt. Whether or not Longfellow actually thought that the slaves songs were only Biblical, or if it was a metaphor, this association of slave music with Christian (meaning at this time European) themes is reminiscent of George Pullen Jackson’s problematic argument that slave spirituals are only of European origin.2 By placing the black slave in a European Christian context, Longfellow was telling readers not only to think of slaves as melancholic and noble, but also to think of their music within a European framework. While this is not surprising for a white New Englander at the time, is shows a consciousness for the genre of music that slaves were thought to sing.

Another theme in this poem is that of secrecy. For example, “in this hour, when night is calmest,” or in the dead of night, the slave sings “in a voice so sweet and clear/That I could not choose but hear,” showing that Longfellow may have been aware of the tradition among slaves to sing and worship under the cover of darkness so as to avoid the eyes of slaveholders. It is within this shroud of privacy that the slave is able to sing out clearly about the pain of slavery, and the desire to escape.

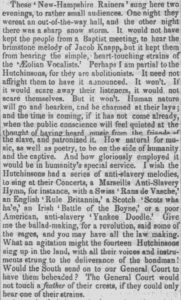

An excerpt from a review of a concert by the Hutchinson Family Singers in late 1842. The review was generally positive, but the author, Parker Pillsbury, hoped for more focus on abolition in the future.

At the end of the poem, Longfellow alludes to the abolitionist cause, asking the question so often repeated in abolitionist music: who will fight for the downtrodden slave? Returning to the review I originally planned to write about, we can see common thread between Longfellow’s question, and the reviewer’s wish that the Hutchinsons would take abolitionism up with more fervor.3 While the Hutchinsons were known abolitionists, their repertoire did not include any specifically abolitionist songs in 1842 (those would be added less than a year later.)4 Through both the poem and the review, we can see the abolitionist movement calling for more devoted action, and realizing that music would be important for both inspiring an empathy vision of slaves, and creating excitement for the cause.

1 Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. “The Slave Singing at Midnight.” From Poems on Slavery. Liberator. Boston, Dec. 30, 1842.

2 George Pullen Jackson. White and Negro Spirituals: Their Lifespan and Kinship. Locust Valley, New York: Augustin Publisher, 1943.

3 Parker Pillsbury. “The Hutchinson Singers.” Liberator. Boston, Dec. 30, 1842.

4 Dale Cockrell, ed. Excelsior: Journals of the Hutchinson Family Singers 1842-1846. Pendragon Press: 1989, 94.