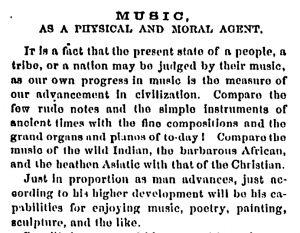

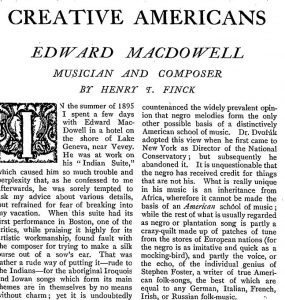

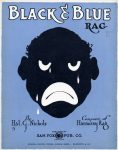

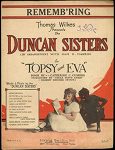

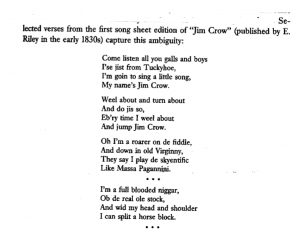

As someone who is currently studying musicology, one of the main tasks required of me is to use music as a clue to make larger claims about society at that time. In other words, I sleuth around in musical documents to figure out how people thought. Just like any primary source, music leaves us a trail that can bring us to bigger discoveries about human nature. So this week, I decided to embark on the task of using musical documents to bring light popular sentiments about black Americans.

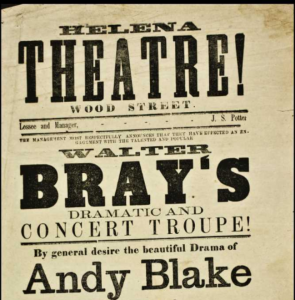

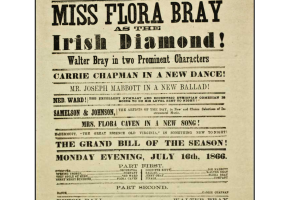

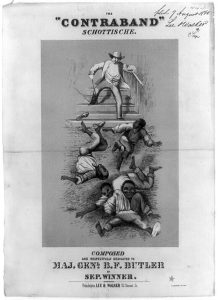

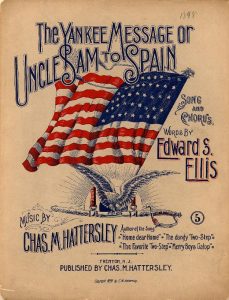

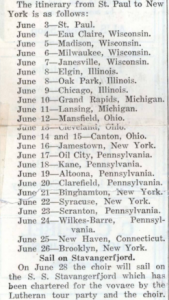

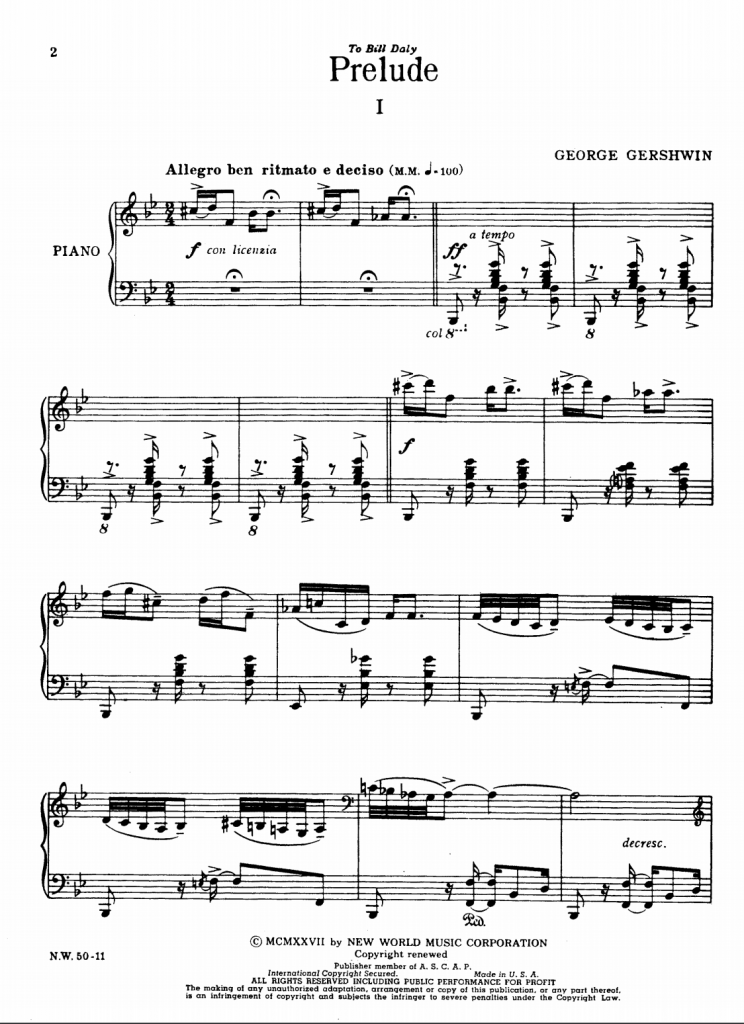

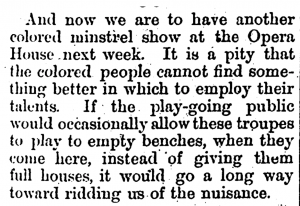

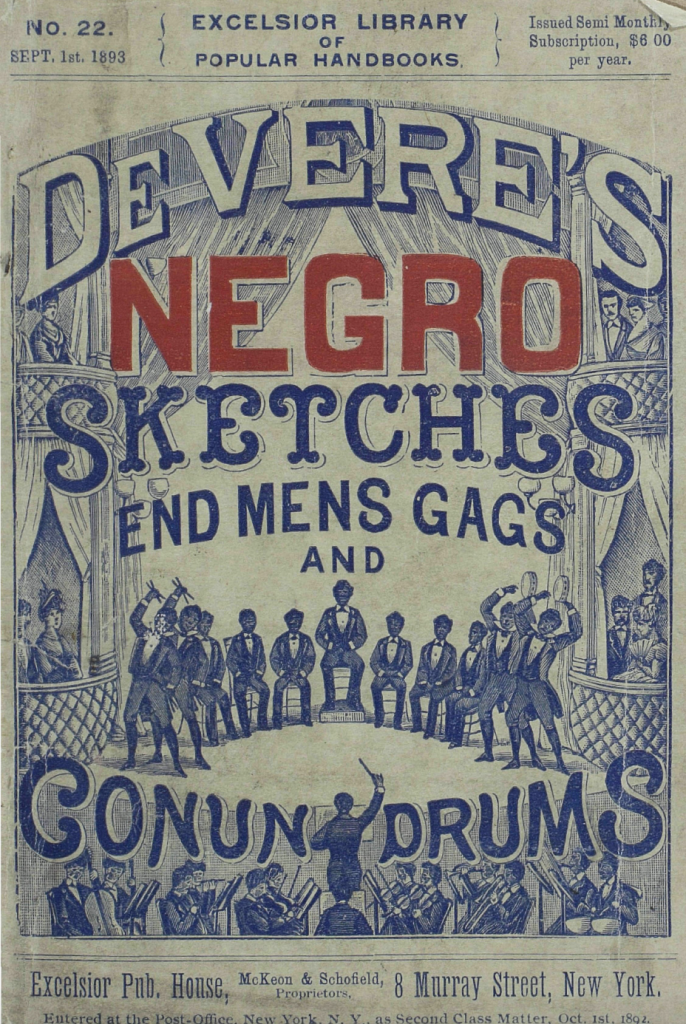

I decided to take a closer look at this document:

(It’s a little blurry here, so take a look here for a clearer picture: https://www.loc.gov/pictures/resource/cph.3b35698/)

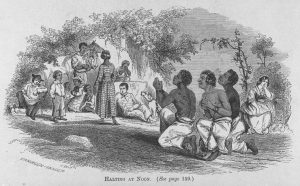

This is a sheet music cover for a piece titled “the Contraband Schottische” written by Septimus Winner in 1861 (the beginning of the Civil War). Winner dedicated this piece of music to Union General Benjamin F. Butler. Butler was in charge of implementing the “Contraband Decision” in which escaped slaves who retreated to the North during the Civil War were considered “contraband” or illegally stolen goods. This allowed Slaves to live in a state not being owned but also not being free in the North. This was decided in retaliation to the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 in which slaves were to be returned to their masters if caught after escaping.1 On the cover of “the Contraband Schottische” there is a cartoon depicting a slave owner chasing his four black slaves rolling down the hill as if they are merely goods. Although the Contraband Decision ended up being a helpful decision for slaves as a side effect, we can’t sit here and celebrate Butler, he wasn’t even an abolitionist after all.

The depiction of slaves in this cartoon gives us an inside look into some of the attitudes held by society at the time. In this cartoon, slaves are illustrated to be synonymous with products or goods, as they are rolling down the hill like a sack of potatoes falling out of an 18-wheeler.

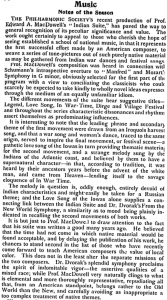

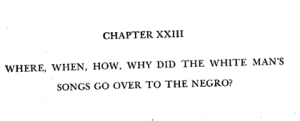

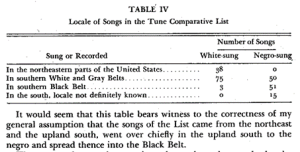

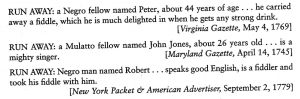

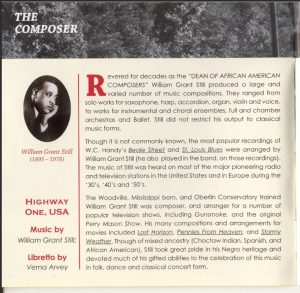

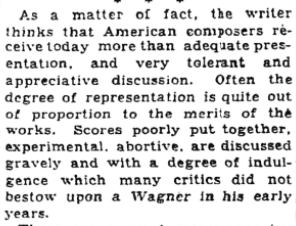

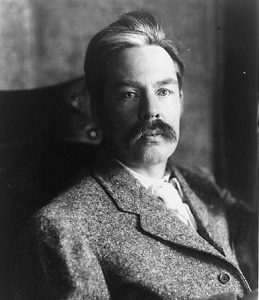

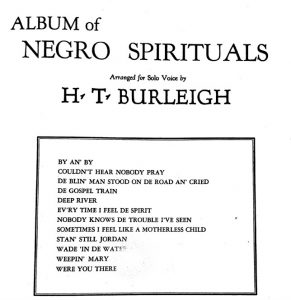

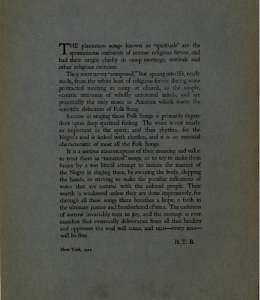

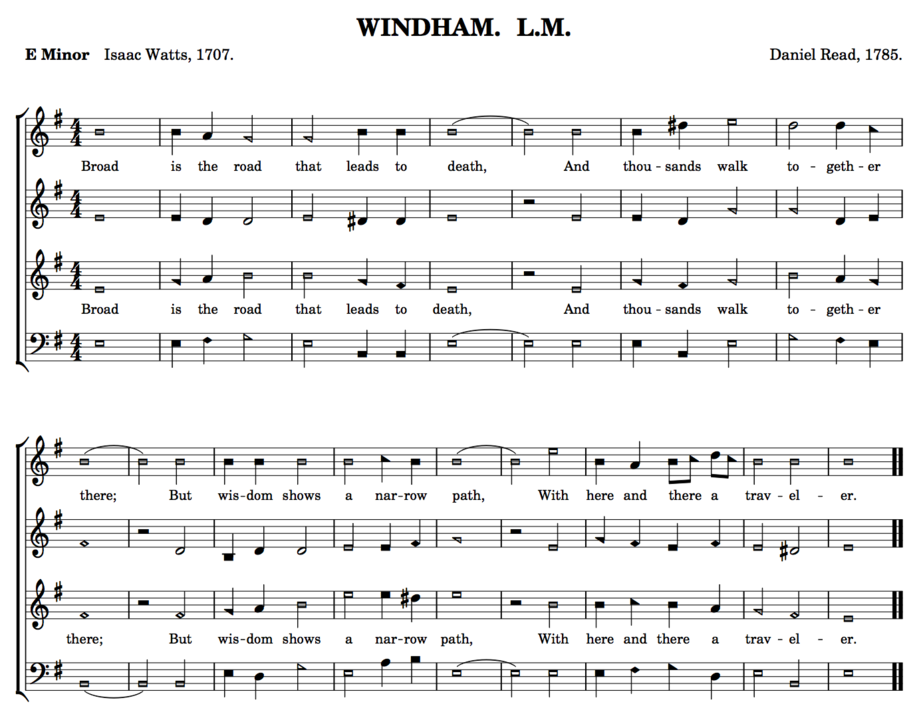

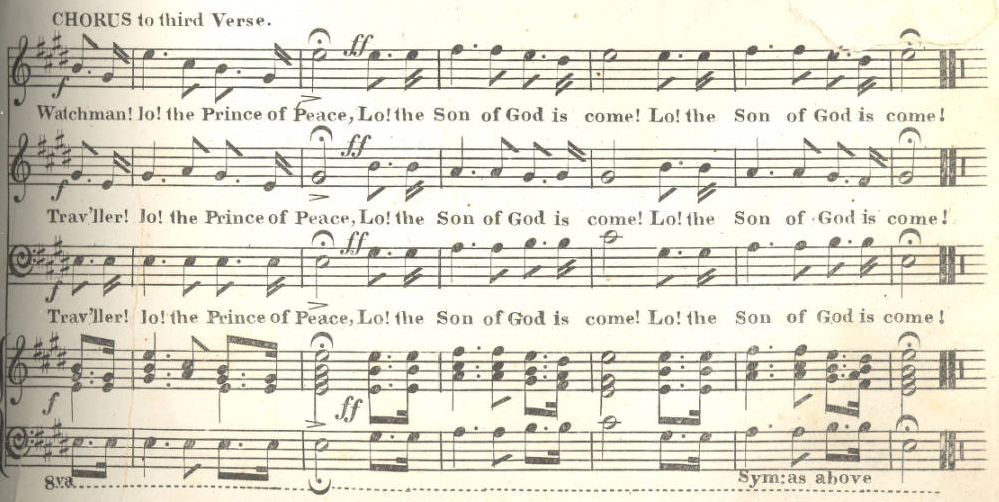

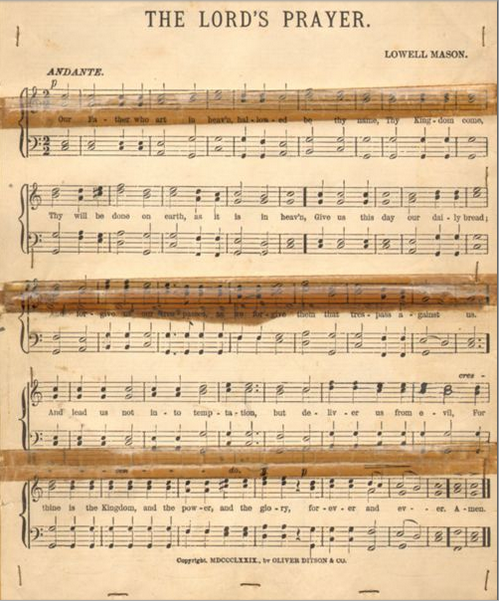

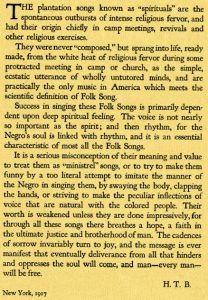

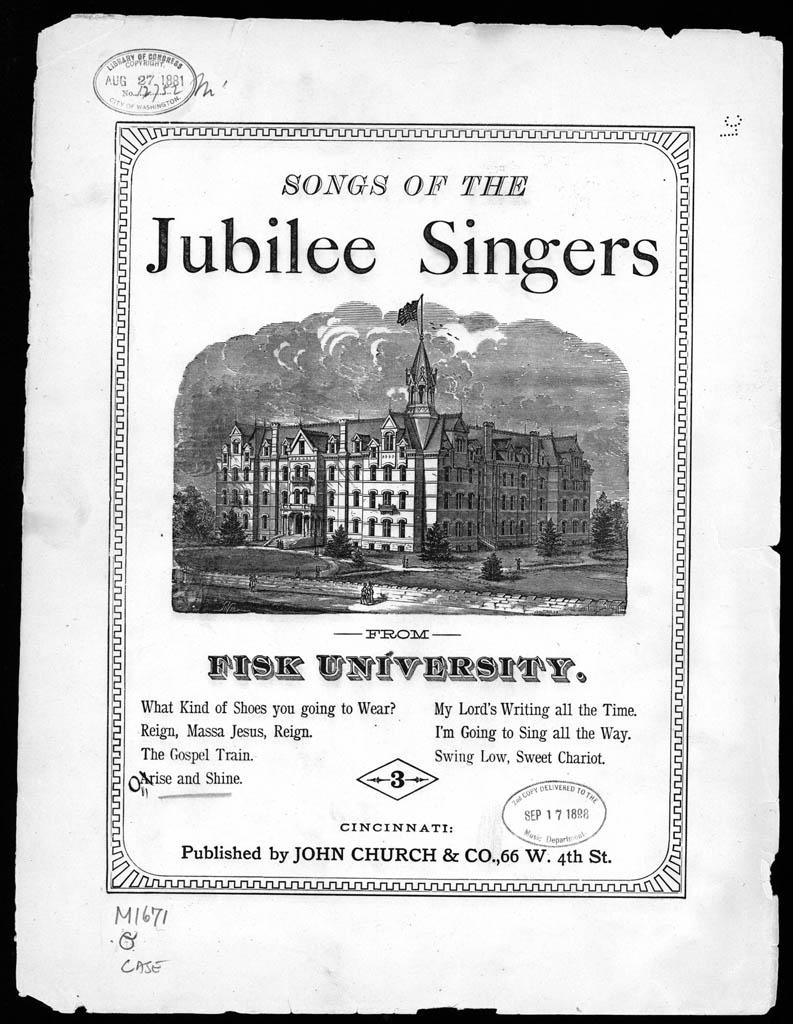

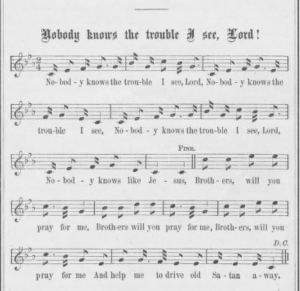

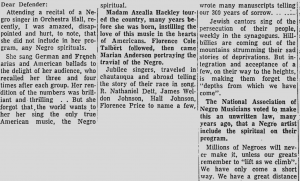

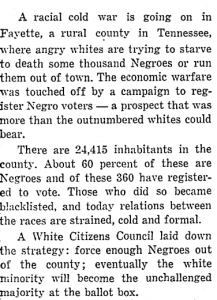

This sentiment of black Americans being treated as “property” or “goods” seems to infiltrate and inform other assumptions about their intellectual ability or identity as functioning humans. If we fast forward to 1943, this idea develops into another held by author George Pullen Jackson in his book White and Negro Spirituals. He holds the belief that black Americans are not capable of producing sophisticated spirituals, and therefore, must have developed all of their music from the influence of Europeans.

“We know that our fathers (Europeans) brought to this land a rich and hoary heritage of folk melody. We know that the negro slave entered into this heritage eventually by adopting it to the extent of his ABILITIES and desires”.2

This quote infers that black Americans would not have the ability to create music as sophisticated as Europeans. By looking at these documents surrounding music, we can see that the sick attitudes of black Americans as “goods” or “property” and the conclusion that they therefore can not produce sophisticated music are rampant for over a hundred years. That’s pretty disgusting.

[1]

[1]

[2]

[2]

![[Members of the Bog Trotters Band, posed holding their instruments, Galax, Va. Back row: Uncle Alex Dunford, fiddle; Fields Ward, guitar; Wade Ward, banjo. Front row: Crockett Ward, fiddle; Doc Davis, autoharp]](https://cdn.loc.gov/service/pnp/ppmsc/00400/00401r.jpg)

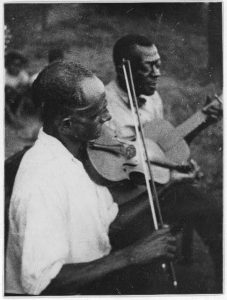

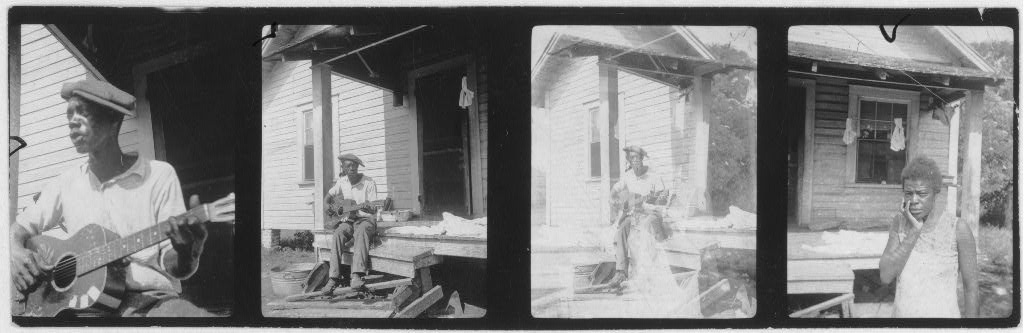

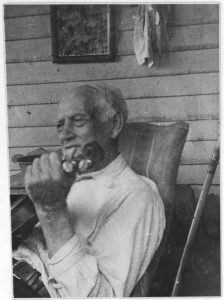

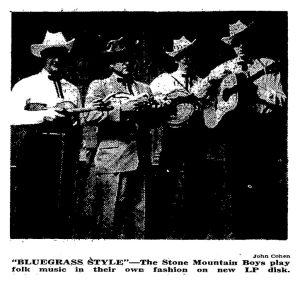

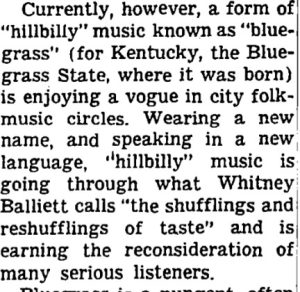

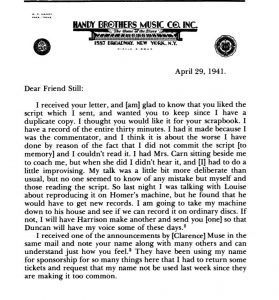

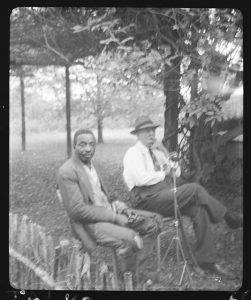

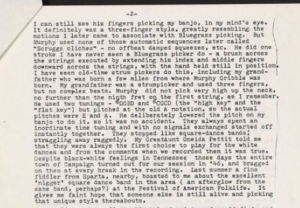

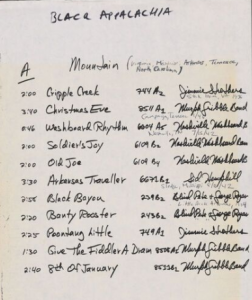

When I found a set of manuscripts collected by Alan Lomax on the playing of musicians in Black Appalachia, the last thing I expected was to end up reading about Earl Scruggs. Nevertheless, this letter from Stu Jamieson on field recordings done in 1946 of a trio of Black Appalachian musicians connected directly into our discussions of bluegrass music from Thursday’s class. The recordings this letter is referencing are of Murphy Gribble, John Lusk, and Albert York on banjo, fiddle, and guitar respectively. Apparently a banjo player himself and familiar with the rise of bluegrass by the time this letter was written in about 1978, Jamieson writes to a friend and scholar at the Library of Congress about the Gribble’s particular styles of banjo picking and fingering. As with Bill C. Malone, part of the reason his recounting is convincing because of his own study and experience with the styles he discusses.

When I found a set of manuscripts collected by Alan Lomax on the playing of musicians in Black Appalachia, the last thing I expected was to end up reading about Earl Scruggs. Nevertheless, this letter from Stu Jamieson on field recordings done in 1946 of a trio of Black Appalachian musicians connected directly into our discussions of bluegrass music from Thursday’s class. The recordings this letter is referencing are of Murphy Gribble, John Lusk, and Albert York on banjo, fiddle, and guitar respectively. Apparently a banjo player himself and familiar with the rise of bluegrass by the time this letter was written in about 1978, Jamieson writes to a friend and scholar at the Library of Congress about the Gribble’s particular styles of banjo picking and fingering. As with Bill C. Malone, part of the reason his recounting is convincing because of his own study and experience with the styles he discusses.

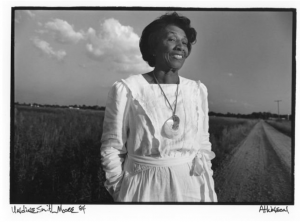

woman, but not in the same “down on their luck” way that most people would expect country music to be presented. In her song,

woman, but not in the same “down on their luck” way that most people would expect country music to be presented. In her song,

[2]

[2] [3]

[3]