Many people are well-aware of the classic rock one-hit wonder “Black Betty” by Ram Jam and its legacy in film, television, advertisements, and other forms of popular culture entertainment. Personally, I quite enjoy the song and I find it to have a great percussive groove and a catchy melody with some rather interesting rhythmic modulations and shifts. (Link below in case you may not be familiar with the song)

Ram Jam – Black Betty (Official Audio)

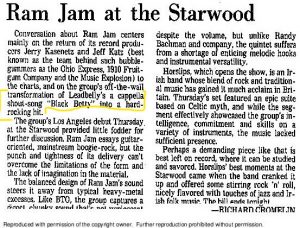

However, not many people might not be aware of its origins, especially in the context of black American music. Ram Jam did credit the blues and folk artist Leadbelly for the origin of their cover and it was advertised as a cover, as can be seen by Richard Cromelin’s mixed review of Ram Jam’s concert at the Starwood in Los Angeles [1]:

[Here is Leadbelly’s version of Black Betty]

While Leadbelly has been typically credited as such, he cannot fully take credit for something he recorded as a folk artist, as Henry Edward Krehbiel argued that folk songs needed to be birthed originally by a group of people rather than an individual artist [2]. The source of the song is regularly contested as well as the original meaning of what a “Black Betty” could have been, whether it be an object or a person. Some sources claim “Black Betty” could have been used as early as the beginning of the 19th century to describe a musket or a liquor bottle, and it is very plausible those could be meanings that would be applied to the Black Betty in the song. One source I found particularly interesting was our favorite folk song collectors, John and Alan Lomax.

In their collection of songs of the Southern chain gangs, the Lomaxes documented “Black Betty” sung by “a convict on the Darrington Farm in Texas” and what they understood “Black Betty” was:

“Black Betty is not another Frankie, nor yet a two-timing woman that a man can moan his blues about. She is the whip that was and is used in some Southern prisons… where […] whipping has been practically discontiuned…” [3]

Being that Leadbelly was also a member of Texas prison chain gangs, its very plausible that he learned the song and many others there, and there may also be a trail that could be investigated further into the musics of enslaved blacks in the US. Therefore, this demonstrates a rather interesting transmission of music from a possible origin in slave songs to white musicians like Ram Jam. They did manage to give credit to the artist who had a definitive recording, which I find to be at least somewhat conscious on their efforts as recording artists in the American popular music scene, but it should be worth noting the influence of black folk music that was felt as late as the 1970s and that we are likely still feeling today.

Notes

[1] Cromelin, “Ram Jam at the Starwood”

[2] Krehbiel, “Songs of the American Slaves,” 22

[3] J.A. Lomax, A. Lomax, “American Ballads & Folk Songs,” 60

Bibliography

Cromelin, Richard. “Ram Jam at the Starwood.” Los Angeles Times (1923-1995), Nov 12, 1977. 1, https://search.proquest.com/docview/158397115?accountid=351.

Krehbiel, Henry Edward. “Songs of the American Slaves” in Afro-American Folksongs: A Study in Racial and National Music (New York: Frederick Ungar Publishing Co., 1914), 11-28.

Lomax, John A., Lomax, Alan. “Songs from Southern Chain Gangs” in American Ballads & Folk Songs (New York: Macmillan Co., 1935), 57-86.