As I embarked on mapping the musical traditions in colonial Mexico, my teammates and I were quite frankly overwhelmed with a vast time period, the vast geography, and despite the amount of music being made, we were faced with a scarcity of primary and secondary sources alike. One way in which we were able to come into contact with primary sources is through the online database at the National Autonomous University of Mexico. This database has a large amount of the Villancicos which were a popular form of music at the time. A villancico is now known as a Christmas carol, but during the colonial period in Mexico, these songs were often set to love poems, poetry, or religious text. They were sung in the vernacular and had an alternating refrain and verse. Moreover, villancico’s varied widely and there were different genres such as a villancico negrilla which depicted the style and dance of African slaves in the colonies1.

Before we begin, I do want to clarify what a chapelmaster was. During the era of colonization, chapelmasters were in charge of all music at a cathedral and often composed and performed in the cathedral. The job of Chapelmaster was reserved for individuals with musical talent and Spain sent chapelmasters from all over Europe to preside over the cathedrals in the Spanish colonies. Furthermore, cathedrals were the place in which all ‘art music’ was performed. basically, they were the concert halls of colonial Mexico2.

The villancico I would like to look at for the purpose of this blog post is by a chapelmaster named Antonio Slazaar and was written between 1650 and 1715. The name of this song is “Va de vejamen” which translates to “goes from humiliation”. Antonio Salazar was originally born in Spain and became the chapelmaster of the Puebla Cathedral and later at the Mexico City Cathedral. Antonio Salazar is also one of the most famous composers of the Baroque period in Mexico.

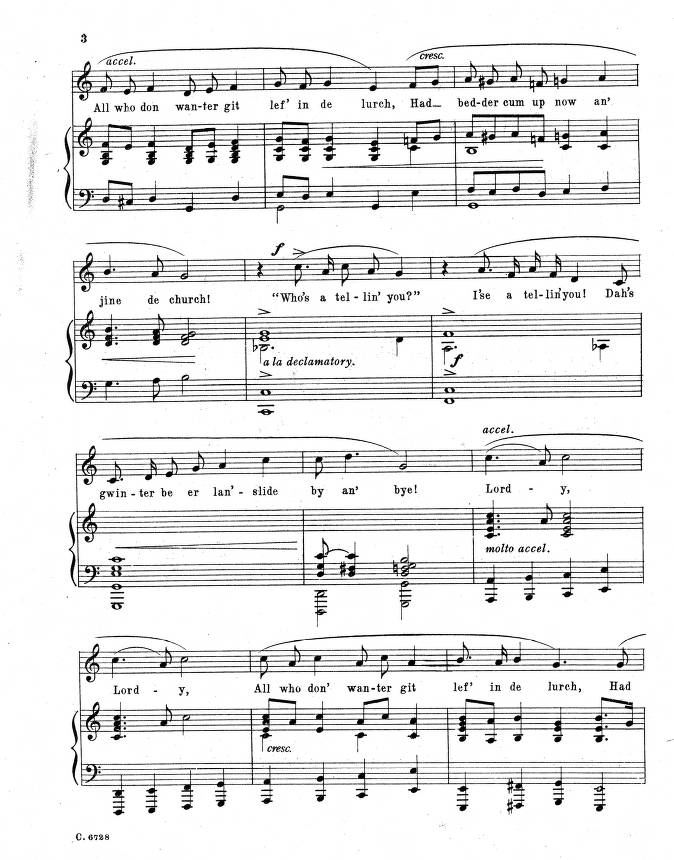

“Va de vejamen” is a part of Salazar’s set of 6 songs called “A sies de la Natividad de Nuestra Señora” or “6 to the nativity of our lady”. Salazar’s piece is about the Christmas season, but not all villancicos were and I want to be clear about that because it is often assumed all villancico’s are carols. I inserted a modern recording of Salazar’s piece below. Something interesting to note is how similar it sounds to a renaissance madrigal. This similarity is common with villancico’s. There is also percussion instrumentation and a strummed string instrument.

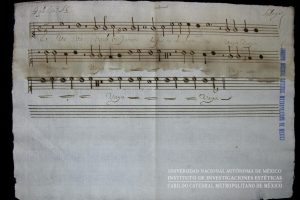

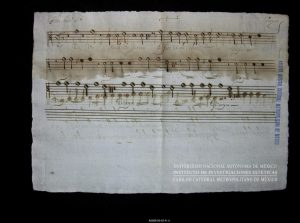

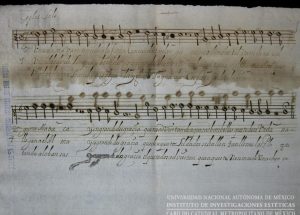

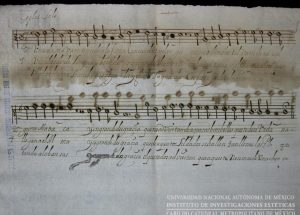

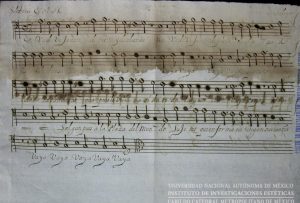

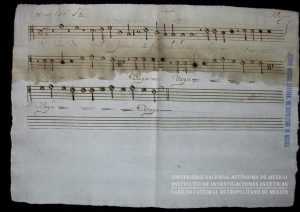

The piece itself luckily was preserved well and we have digital access through the National Autonomous University of Mexico database. It includes the parts for the different instruments and voices all written separately. I would encourage you to listen again and try and follow along in the score, especially the tenor3.

1“Repertoire.” San Francisco Bach Choir: Antonio de Salazar. Accessed December 12, 2021. https://www.musicanet.org/sfbc/repertoire/salazara.html.

2Pedelty, Mark. Musical Ritual in Mexico City: From the Aztec to NAFTA. Austin, UNITED STATES: University of Texas Press, 2004. http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/stolaf-ebooks/detail.action?docID=3443236.