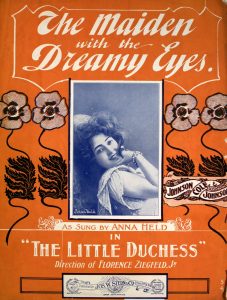

James Weldon Johnson and his brother John Rosamond Johnson were musicians, writers, entrepreneurs, and powerful figures of what came to be known as the Harlem Renaissance. Beyond being known for writing “Lift Every Voice and Sing” which has been called the black national anthem, Johnson and Johnson thrived as songwriters in New York City during the Tin Pan Alley era of popular music, in which songwriters would churn out sheet music to be sold or recorded. In James Weldon Johnson’s autobiography “Along this Way”1 Weldon Johnson explains his process behind writing a hit song titled The Maiden With the Dreamy Eyes.

“In those days the royalties of a writer depended largely upon the young fellow who would buy a copy of the song and take it along with him when he went to call on his girl…In writing “The Maiden with the Dreamy Eyes” we gave particular consideration to these fundamentals. It needed little analysis to see that a song written in exclusive praise of blue eyes was cut off at once from about three-fourths of the possible chances for universal success; that it could make but faint appeal to the heart or pocketbook of a young man going to call on a girl with brown eyes or black eyes or gray eyes. So we worked on the chorus of our song until, without making it a catalogue, it was inclusive enough to enable any girl who sang it or to whom it was sung to fancy herself the maiden with the dreamy eyes (160).”

James Weldon Johnson makes it perfectly clear that in writing this piece of music, the objective was to make the song appeal to as large of a group of people as possible, something that is accomplished by literally listing several eye colors in the song. A 1902 recording of the song by the Victor Recording Company, sung by a Canadian tenor named Harry Macdonough accomplishes the precise sweetness that Weldon Johnson refers to in his account. For another, more recent recording check out this version by Melinda Doolittle.

Part of the specific success of this song was due to new customs surrounding dating at the start of the 20th century. Magazines and journals made money off of marketing to new audiences and age groups, especially to a certain subset of young people who would eventually be called teenagers, Beth Bailey2 writes

“The middle-class arbiters of culture, however, aped and elaborated the society version of the call. And, as it was promulgated by magazines such as the Ladies Home Journal, with a circulation of over one million by 1900, the modified society call was the model for an increasing number of young Americans (15).”

This new middle class is also something we tend to think of as predominantly white, a market that Weldon Johnson found great success in despite being a black artist. In his autobiography, he wonders if consumers of his music are aware of his identity, writing about a letter he received as follows.

“The very serious-looking Mr. Bok read me the letter and laughed uproariously over it. I laughed too; but me laughter was tempered by the thought that there was anybody in the country, notwithstanding the locality being Georgia, who, knowing anything at all about them, did not know that Cole and Johnson Brothers were Negroes (196).”

Everything we know about the creators behind The Maiden with the Dreamy Eyes makes it a piece of black art, with words by a black poet and a musical arrangement by a black composer, but in standard examples of what “black music” is, it would be highly unlikely to ever hear this song. In my preliminary search of Alan Lomax’s photo collection tied to his work on folk music in the south in the 1930’s I found no instances of pianos, despite the fact Weldon Johnson’s music, published some 30 years prior was based around a piano.

When music is cataloged and categorized, everything that doesn’t fit into those boxes gets left to the side because it fails to serve the central narrative about what that particular music means. While The Maiden with the Dreamy Eyes is goofy and a clear grab for money, what new stories can we explore when it is as much of a piece of black music as any recording taken by Alan Lomax in the South?

1Johnson, James Weldon. Along This Way : The Autobiography of James Weldon Johnson. New York: Viking Press, 1965.