I am a huge fan of both Florence Price’s and Serge Koussevitzky’s works, having played and listened to a number of them myself. I (with the generous help of Professor Epstein and Karen Olson) tracked down a letter from Price to Koussevitzky dated 5 July 1943 in a scholarly edition of Price’s Symphonies 1 and 3, edited by Rae Linda Brown and Wayne Shirley1.

Price opens this letter by writing:

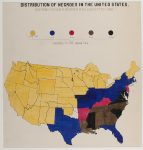

“To begin with I have two handicaps – those of sex and race. I am a woman; and I have some Negro blood in my veins.”

She writes about her cultural heritage and how she’s worked to incorporate her culture into her music. Price goes on to say she “truly understands the real Negro music.” She finishes her letter by directly asking Koussevitzky, “will you examine one of my scores?” Over the course of nine years (1935 – 1944), Price wrote seven letters to Koussevitzky. She never got a personal response back. On two occasions (17 November 1943 and 31 October 1944), his secretary responded to her, but we do not know what the response said. In October 1944, Koussevitzky looked at one of her scores, but did not program any of her works.

Serge Koussevitzky was the conductor of the Boston Symphony, composer, and world-renowned double bass virtuoso. He was known for not only supporting and programming works by living American composers, but commissioning new works for the Boston Symphony as well. Florence Price knew this, and knew her works were being perceived through a number of lenses by her audience. She admits this in her letter, and asks Koussevitzky to look past it and program her work anyway. Unfortunately, he never did.

We could view this as a concrete example of something that is indicative of the available sources about female composers, and composers of color. Clearly, there is significantly less information out there about marginalized groups. Even in our own music library, the imbalance between sources is obvious. When I searched for scores by Florence Price in our library database, I found that the library has 29 physical scores. When searching for a white male composer of similar dates, Jean Sibelius, I found the library has 119 sources. Well, maybe that’s because Price is American and Sibelius isn’t? What about Charles Ives? 115 scores in the library. I don’t think we can dodge the real reason any longer. Florence Price said it herself: she is a female composer of color, and that is why her work is lesser known today. People like Koussevitzky who claim to want to support American composers, but only if the composer fits a certain mold, are the reason these composers are lesser known today. We can start the work to fix this problem now, and great work is already being done to bring underrepresented works to light, but it should’ve started a long time ago.

Works Cited:

[1] Price, Florence, Rae Linda Brown, Wayne D. Shirley, and Florence Price. “Symphonies nos. 1 and 3 ” Middleton, Wis: Published for the American Musicological Society by A-R Editions, 2008.