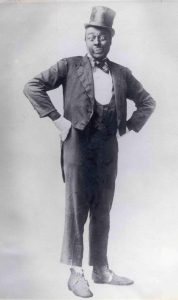

Every popular source about Bert Williams sings his praises. Although he lived (1892-1922) during a time when racial inequality was blatant and accepted, he had an extremely successful career in the entertainment industry. He was the first black man to have a leading role in a film and a leading role on Broadway, the best-selling black recording artist before 1920, and was hailed as one of the greatest comedians of his time.

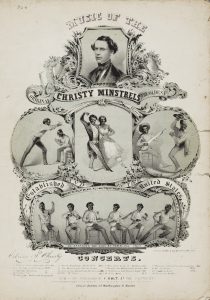

Bert Williams was also a black minstrel performer. He and his partner Geroge Walker worked to reclaim minstrelsy and entertainment from the white performers that so often belittled and violated black life and culture through minstrel performances. And judging by his successful career, Williams was able to achieve some degree of reclamation.

But in his article, titled “The Unfunny Bert Williams,” published in the Chicago Defender, one of the nation’s largest black newspapers, Enoch Waters juxtaposes this vision of success with a story about Bert Williams. Basically, Eddie Cantor, a white comedian, visits Williams in his room during a dinner party, only to find that Williams is eating dinner alone. Cantor accuses him of being exclusive, but Williams has to explain that he has been refused service in the restaurant downstairs, due to his race. This exposes the paradox in their society; Bert Williams is exceedingly famous among white people, loved by all, yet he still has his rights stolen from him due to the racism of the time.

But in his article, titled “The Unfunny Bert Williams,” published in the Chicago Defender, one of the nation’s largest black newspapers, Enoch Waters juxtaposes this vision of success with a story about Bert Williams. Basically, Eddie Cantor, a white comedian, visits Williams in his room during a dinner party, only to find that Williams is eating dinner alone. Cantor accuses him of being exclusive, but Williams has to explain that he has been refused service in the restaurant downstairs, due to his race. This exposes the paradox in their society; Bert Williams is exceedingly famous among white people, loved by all, yet he still has his rights stolen from him due to the racism of the time.

This incident happened during Bert Williams lifetime, but Enoch Waters considered it relevant material in 1954 when he published his article. And I believe that it is still relevant today. No matter the value of a person of color, or their “success,” they are still subject to the racist thoughts and systems present in our society.

Citations

Waters, Enoc P. “Adventures in RACE RELATIONS: The Unfunny Bert Williams.” The Chicago Defender (National Edition) (1921-1967), Aug 14, 1954. https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/adventures-race-relations/docview/492840513/se-2?accountid=351.

“Bert Williams (1874-1922).” Library of Congress, biographies, https://www.loc.gov/item/ihas.200038860/#

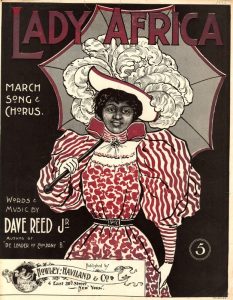

This first photo is taken from a popular (in the 1800s) cartoon by Currier and Ives called Blacktown, a satire aimed at making fun of black people. Its one of the first images that results from the search of the word “banjo,” yet we know that banjo was a popular instrument in black communities. Its a useful source to pair with Southern and Gidden’s points, because it places the banjo in the black musical canon, yet it’s entirely controlled by the white people who made it.

This first photo is taken from a popular (in the 1800s) cartoon by Currier and Ives called Blacktown, a satire aimed at making fun of black people. Its one of the first images that results from the search of the word “banjo,” yet we know that banjo was a popular instrument in black communities. Its a useful source to pair with Southern and Gidden’s points, because it places the banjo in the black musical canon, yet it’s entirely controlled by the white people who made it. This picture, from 1901, is of a “picaninny” performing child, a popular vaudville act, in which children performed for white spectators, often for humor, under the hand of a white adult female. The children often travel with the troupe without their families. Again, the mandolin places the instrument into the black music narrative, but the picture is likely taken by a white person for other white people. I find this picture especially disturbing, as the child is nameless, naked, and smiling (is she happy?). She is viewed as an object for entertainment; property to the act. This is another example of white people in control: not only of the picture and narrative, but of the life of this child.

This picture, from 1901, is of a “picaninny” performing child, a popular vaudville act, in which children performed for white spectators, often for humor, under the hand of a white adult female. The children often travel with the troupe without their families. Again, the mandolin places the instrument into the black music narrative, but the picture is likely taken by a white person for other white people. I find this picture especially disturbing, as the child is nameless, naked, and smiling (is she happy?). She is viewed as an object for entertainment; property to the act. This is another example of white people in control: not only of the picture and narrative, but of the life of this child.