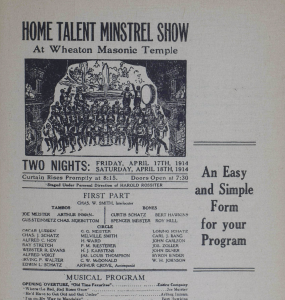

Or at least that’s what Harold Rossiter encourages in his book How to Put on a Minstrel Show, published in 1921. According to Rossiter, the objection of giving a minstrel show is that it “is the one form of entertainment of which the public never seems to tire and a show can be safely produced at least every two years and in the larger towns or cities a show every year is not too often” (1). After this assurance that the readers’ minstrel show will be popular simply based on the fact that the public desires such a show, Rossiter goes on to discuss how to successfully put on a minstrel show, through musical examples, joke suggestions, instructions on how to put on and take off blackface makeup, and a sample program.

One chapter in his book is titled “Jokes for Minstrel Show.” In this section, before providing some example jokes, he advices:

“Don’t let the end-men use too much negro dialect in telling their jokes. The average amateur negro dialect is almost pitiful, and they nearly always overdo it with the result that the audience fails to understand a word they say, and the joke goes flat. Have them use good, plain English” (1).

Good, plain English. This makes the assumption that African American individuals, whom Rossiter is encouraging his performers to stereotypically over-emulate, use a different form of the English language that is so opposing than his own that if his performers attempted to recreate it, the joke will fail. He exoticizes the African American population, establishing them as an “other” group.

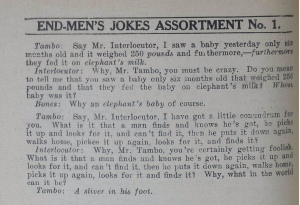

In this quote, Rossiter also mentions the “end-men.” In minstrelsy, these were the performers in blackface who were the brunt of the jokes. Rossiter gives examples of jokes between end-men named Brother Tambo and Brother Bones, and an Interlocutor who, according to Rossiter, “is not blacked up; he always performs his part white-face” (1). Here’s an example of one of these jokes:

Each of Rossiter’s jokes in How to Put on a Minstrel Show portrays the Interlocutor, who is white in the production, as the wise, intelligent individual always correcting and ridiculing Brother Tambo and Brother Bones, who are both in blackface.

These jokes send the overt, racist message that white individuals are, in addition to more eloquent in speech, smarter and must correct the foolish mistakes of the “black” characters.

Just six years before Rossiter published his book, in 1915, the Chicago Weekly Review published an article that highlights the craving that audiences demonstrated for minstrel shows, emphasizing their popularity in white society in the early 1900s and exemplifying the humor white audiences found in ridiculing the blackface performers and therefore the African American race. The author, Sylvester Russell, writes that this specific minstrel show, containing blackface, was a “musical comedy” introducing “Billy King, one of the greatest and funniest blackface comedians of minstrel reputation” (2)

Audiences enjoyed minstrel shows, audiences found blackface hilarious, audiences were obsessed with ridiculing the African American population. Eric Lott writes in his introduction to Love and Theft: Blackface Minstrelsy and the American Working Class, “Although it [minstrelsy] rose from a white obsession with black (male) bodies which underlies white racial dread to our own day, it ruthlessly disavowed its fleshly investments through ridicule and racist lampoon” (3).

As Lott explains, as well as how these primary sources exemplify, the racists beliefs of white Americans in the early 20th century led to the popularity of the minstrel show. While minstrelsy doesn’t carry the comedic weight it once did, it is important to recognize what this history means in terms of racism in America today – how it formed, what actions led to the current attitudes of some individuals, and how we use these horrible historical references to make changes in how race is perceived now.

Bibliography:

(1) Rossiter, Harold. How to Put on a Minstrel Show. Chicago: Max Stein Publishing House, 1921. Afro-American Imprints. https://infoweb.newsbank.com/iw-search/we/Evans/?p_product=EAIX&p_theme=eai&p_nbid=U4EY56ALMTU3MDAzNTM1MDg1NToxOjEzOjE5OS45MS4xODAuMjE&p_action=doc&p_queryname=page7&f_qdnum=-1&f_qrnum=-1&f_qname=6&f_qnext=&f_qprev=&p_docref=v2:13D59FCC0F7F54B8@EAIX-154E9B0050389E50@S1879-1606D62438F47E6D@37.

(2) “Chicago Weekly Review.” Freeman (Indianapolis, Indiana), July 31, 1915: 5. Readex: African American Newspapers. https://infoweb.newsbank.com/apps/readex/doc?p=EANAAA&sort=YMD_date%3AA&page=1&f=advanced&val-base-0=minstrel%20show&fld-base-0=alltext&bln-base-1=and&val-base-1=blackface&fld-base-1=ocrtext&docref=image/v2%3A12B28495A8DAB1C8%40EANAAA-12CBF3B4D7999C58%402420710-12CBE4FDE2B80BD8%404-12DF5C8D4F757178%40Chicago%2BWeekly%2BReview&firsthit=yes.

(3) Lott, Eric. Love and Theft: Blackface Minstrelsy and the American Working Class. New York: Oxford University Press, 1993.