Imagine you’re sitting in studio class, getting feedback on your musical performance. Someone describes your performance as “natural-sounding”. We’ve all received notes like this before and wondered: Was that a compliment, or a criticism? Reading through our course materials and seeing a persistent, underlying description of African-American music as “natural-sounding,” I was left asking the same question. The answer, unsurprisingly, is not simple. The common association between naturalness and African-American music is simultaneously demeaning and empowering, and has been both since well before the 20th century.

In Blues People, Amiri Baraka identifies one of the leading criticisms of Blues music as the judgement that it is “raw” or “unrefined”. Baraka traces this back to a fundamental difference between Western and African conceptions of music as “art music” versus “functional music”, which results in “the principle of the beautiful thing as opposed to the natural thing”.1 It is this very principle that has often caused the association of African-American music with a natural sound to be degrading. Blues-players such as Charlie Parker often actually imitate the human voice with their instruments, but in these cases, many critics perceive this type of natural playing as uncultured, hoarse, or raucous.2

James Trotter writes a whole chapter of his 1880 book, Music and Some Highly Musical People, on the music of nature. Though generally venerative of music’s natural origins, Trotter’s content opens the door for exactly the kind of degradations of African-American music that later critics would make of Charlie Parker. Trotter says that it was from nature that “man received his first impressions, and took his first lessons in delightful symphony.”3 While this is a lovely thought, it also places music that emulates nature at the earliest, most primitive point in musical evolution, which opens the door for racist analysis of “natural-sounding” African-American music. Trotter also speaks highly of “the charming music of the birds,” placing birds just below humans in rank.4 Later perversions of this general idea would allow critics to degrade African-American music as more natural-sounding and thus more animalistic, and even savage.

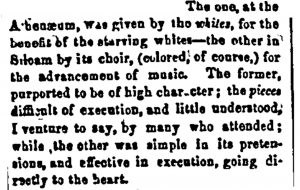

So on the one hand, we have “natural-sounding” African-American music being demeaned as simple, unpolished, and crude. But on the other hand, we have authors like Baraka acknowledging these degradations and reclaiming the natural sound as an intentional and meaningful choice. It came as a surprise to me that this kind of empowerment was present even long before Baraka. A letter to Frederick Douglass published in Douglass’s paper in 1855 compares two recent concerts, one given by white singers, and one by an African-American choir:

“For Frederick Douglass’ Paper from Our Brooklyn Correspondent My Dear Douglass.” Frederick Douglass’ Paper. (Rochester, New York) VIII, no. 6, January 26, 1855: [3]. Readex: African American Newspapers.

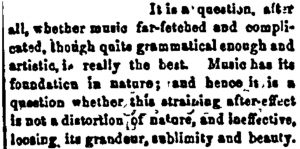

Here we finally have an author who identifies a link between African-American music and nature in a positive manner, asserting that the simplicity he perceives in the music actually enhances its beauty and grandeur.6

From both the letter-writer and Amiri Baraka, we learn that the link between nature and African-American music is fraught with complications. Historically, it has been used to degrade and demean, but even back in the 19th century, some authors acknowledged it as a choice and a strength.

1 Amiri Baraka, Blues People: Negro Music in White America. Perennial, 28-30.

3 James Trotter, Music and Some Highly Musical People. Boston Lee and Shepard, 12.

Works Cited:

Amiri Baraka, Blues People: Negro Music in White America. New York: Perennial, 2002.

“For Frederick Douglass’ Paper from Our Brooklyn Correspondent My Dear Douglass.” Frederick Douglass’ Paper. (Rochester, New York) VIII, no. 6, January 26, 1855: [3]. Readex: African American Newspapers. https://infoweb.newsbank.com/apps/readex/doc?p=EANAAA&docref=image/v2:11BE9340B7A005AB@EANAAA-12C59B54DB3C07D8@2398610-12C59B554C5CF678@2-12C59B5682B4F670@For+Frederick+Douglass%27+Paper+from+Our+Brooklyn+Correspondent+My+Dear+Douglass.

James Trotter, Music and Some Highly Musical People. Boston: Boston Lee and Shepard, 1880. Readex: Afro-Americana Imprints. https://infoweb.newsbank.com/iw-search/we/Evans/p_product=EAIX&p_theme=eai&p_nbid=W4AQ51PGMTU2OTk3NTIzMC45NDYxNDE6MToxNDoxOTkuOTEuMTgwLjE0MA&p_action=doc&p_queryname=15&p_docref=v2:13D59FCC0F7F54B8@EAIX-147E02DC1D1E77C0@10435-1542FF18CF7AA198@9