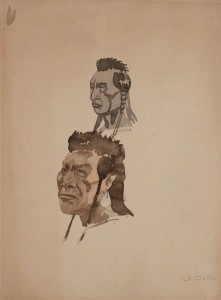

One of the most discussed topics regarding the traditions and beliefs of other cultures and other people outside of western traditions is that of how one can attempt to understand and learn of them, without stepping into the realm of appropriation. This discussion, reflected in our class discussions on the differences between cultural sharing and cultural appropriation, is one that must be discussed, else there are consequences. As someone whose heritage lies in the Nez-Percés tribes of old in Idaho, I often question how much I can delve into the traditions without stepping on the toes of those who came before me. As someone raised in a white household, being brought up on French traditions, I do not know enough of the traditions of my ancestors, yet I have always been raised with the utmost respect for them. This respect is what leads me to crave knowledge in learning more regarding my heritage, yet it’s important to understand that I will never truly understand the traditions and beliefs of the Nez-Percés, as one cannot truly understand without being born and raised in the culture.

Cultural Misunderstandings

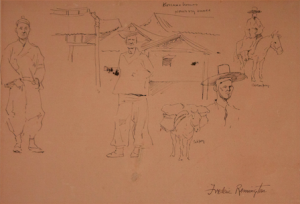

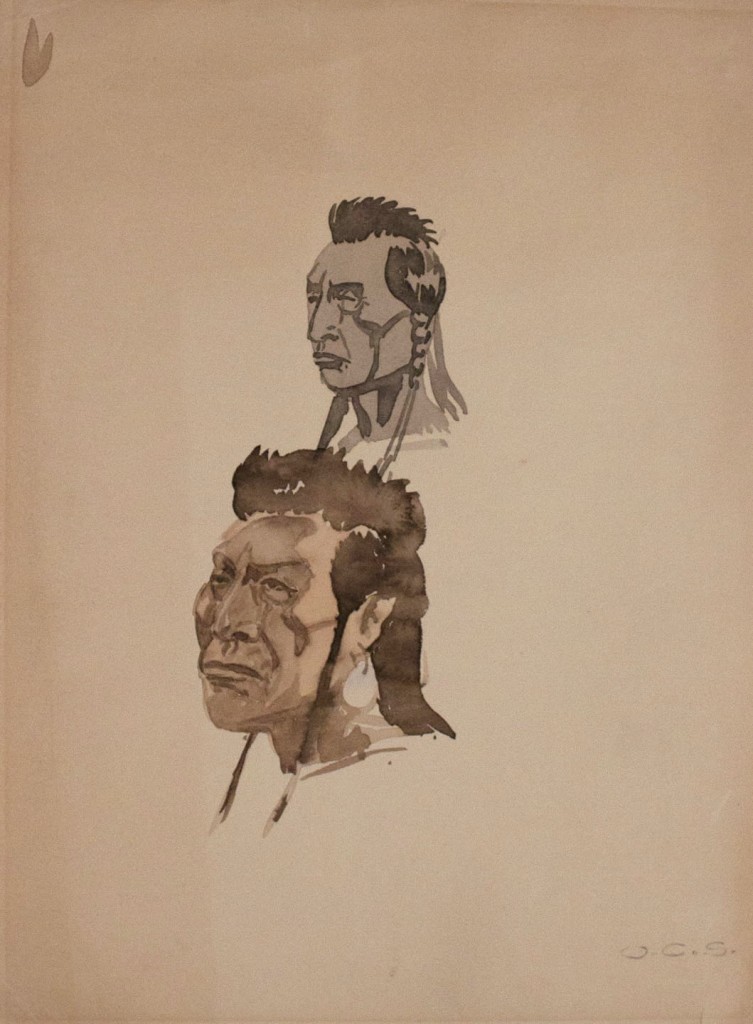

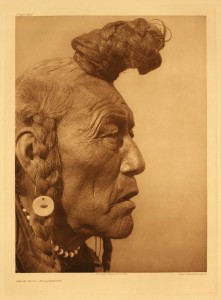

There are many types of cultural misunderstandings, two of which that I will discuss in this post being that of malicious cultural misunderstanding compared to ignorant cultural misunderstanding. In regards to the Nez-Percés, the first type of misunderstanding was what they encountered initially with white folk. One document I looked into was a recount written by a white man named Lawrence Kip, who was with the Escort from the 4th Infantry, regarding the 1855 Indian Council. What I focused on primarily in the recount was his descriptions of the Nez-Percés tribe before and throughout the council. In his first encounter with the Nez-Percés, he refers to it as his “first specimen” of the Nez-Percés. This initial vocabulary, in referring to the approaching tribe as the first “specimen” he encountered already places them below the white man. Without any experience with the tribe, he has already assumed them to be inferior beings to himself, and this will continue throughout his experience with the tribe, as it did in the minds of many other white men.

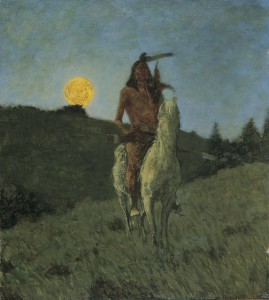

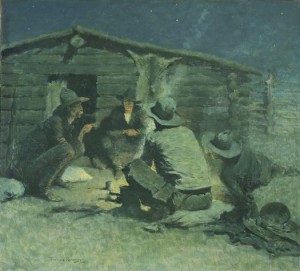

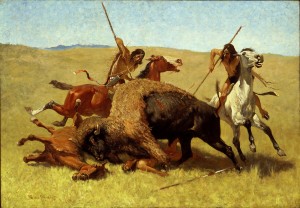

In continuing his description of the natives he encountered, the western world’s infatuation with the exotic was also portrayed. He described them in a majestic light, claiming that they assumed the grace of centaurs, being one with their steeds. They were “gaudily painted,” had “fantastic embellishments flaunted in the sunshine,” and had “fantastic figures” covering their bodies. In the end, he wrapped up his initial description as “wild and fantastic.” To him, they were wild savages, yet they were fascinating, fantastic, and something utterly exotic from what he’d experienced before.

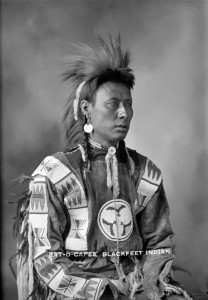

The Nez-Percés were known to be one of the kindest tribes to the white men, yet while visiting one of the Nez-Percés chiefs, Kip lumped them and their enemies, the Blackfoot tribe, together as savages. The lack of distinction between two tribes, one seemingly more violent to the white men than the other, shows the lack of care and thought that the white folk gave the tribes, no matter how kind.

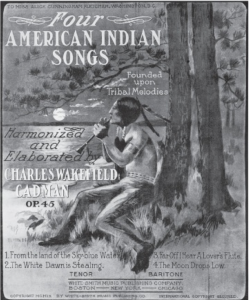

It has been greatly discussed that the musical accomplishments of native americans stray from those in western culture, although that does not in any way diminish their music. Pitches and rhythms that are not in the western music cannot be dismissed as lesser, or incorrect, but must rather be adopted, as they are all music. Kip described their musical instruments as of the “rudest kind,” their singing as “harsh,” and overall “utterly discordant.” Even one who was not adept in music couldn’t find a way to appreciate what he heard, and instead described it in the words that we don’t dare use to describe music. While something may be discordant, it is still appreciated in western culture, unless, it seems, it is a part of another culture altogether, in which case it is dismissed as something that is not music, and something we cannot appreciate in the same manner.

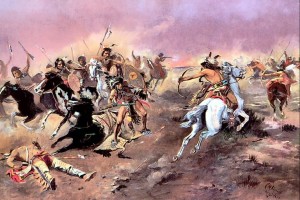

Kip’s description of his experience with the Nez-Percés tribe is not to be taken as a factual and perfect account, as he had his biases. It is important to search other references, as I shall continue to do so in later blog posts. This original conception of the Nez-Percés tribe was something that was later to bring on the Nez-Percés Campaign, where the white men went to war with the tribe. This misunderstanding and refusal to understand other cultures was what brought on violence, and is what I’m referring to as a malicious misunderstanding. While it was not explicitly malicious to begin with, the fact that the newcomers found the native american tribes to be inferior to them was the beginning of homicide. What could be considered a misunderstanding was not solved in an equal and understanding manner, therefore there was no resolution.

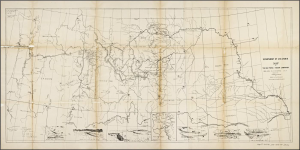

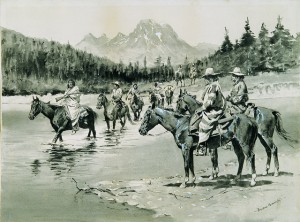

Nez-Percés Campaign

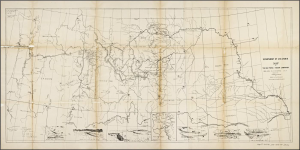

Another very interesting document that I found was a map of the Nez-Percés Campaign. It depicts the path taken by the newcomers in their war against the Nez-Percés, as well as drawings of fighting grounds, military movements, and notes of times and dates when specific events occurred. It is the prime example of the consequences that can happen from cultural misunderstanding and more specifically, the lack of respect and attempt for peace with other cultures.

Nez-Percés Traditions and Religions

The second misunderstanding I’m going to discuss occurs often in today’s world, and is something I’m experiencing currently when researching the Nez-Percés. I am aware that for all of the research I can do, I can only gain a small glimpse into the truth regarding the culture of the Nez-Percés, and I cannot hope to truly understand their culture and traditions. At the same time, in my attempts to research it I hope to gain more insight on something that is both important to me, and should be important to everyone else out there, as it is important to learn and respect other cultures.

In R. L. Packard’s “Notes on the Mythology and Religion of the Nez-Percés,” he goes into detail of first hand accounts of a very small amount of traditions of the Nez-Percés. He gets his information in a discussion with James Reubens, who is a member of the Nez-Percés tribe. Even at the beginning of the conversation, the concept of misunderstanding and lack of respect in learning as portrayed in Reubens’s statement that he was worried Packard only had the “idle curiosity of a white man,” rather than a true passion for learning and respecting Nez-Percés traditions. This statement is a prime example of the issue at hand, where people are ignorant of the cultures they are stepping on and appropriating, yet make no attempts to learn about them in depth. Sometimes, it is due to pure ignorance, as they do not know that there is an issue, but other times it is due to laziness, which is something else altogether that we must combat.

As Reuben continued to discuss Nez-Percés traditions and beliefs, he touched on another prominent barrier in true understanding. He said that “the way we (the Nez-Percés) get our names is a beautiful thing when told in our language, but I cannot tell it well in English.” The language barrier that exists is extremely inhibiting, yet unavoidable. Without knowledge of the language and time spent with the culture, one cannot hope to gain true understanding of it. At the same time, this is another reason people are unwilling to learn, and wish to simply continue living their lives in an ignorant manner.

One tradition that was extremely interesting to learn about was the tradition of how children received their names in Nez-Percés culture. I do not dare to paraphrase the process, as it is complex and deserving of a true description. Even now, I am using a paraphrasing that Packard received in his discussion with Reubens.

“When a child is ten or twelve years old, his parents send him out alone into the mountains to fast and watch for something to appear to him in a dream and give him a name. His success is regarded as an omen, and affects his future character to some extent. If he has a vision, and in the vision a name is given him, he will excel in bravery, wisdom, or skill in hunting, and the like. If not, he will probably remain a mere nobody. Not to every child [boy or girl] is it given to receive this afflatus. Only those serious-minded ones, who keep their thoughts steadfastly on the object of their mission, will succeed. The boy who is frivolous, who allows his attention to be distracted by common objects on his way to the place of vigil, or who while there succumbs to homesickness, or gives himself up to the thoughts about hunting in the woods he has passed, or fishing in the streams he has crossed, will probably fail in his undertaking. On reaching the mountaintop, the watcher makes a pile of stones three or four feet high as a monument, and sits down by it to await the revelation. After some time – it may be three or four days – he “falls asleep,” and then, if fortunate, is visited by the image of the thing which is to bestow upon him his name and the wisdom and power belonging to it.”

Why does this matter to me?

One thing in particular rang with me in reading this description, and that was the line “the watcher makes a pile of stones three or four feet high as a monument” atop the mountains. Towards the end of the section, Packard mentions that “there are many of these little monuments referred to on the mountains of Idaho.” Growing up, I often came across these monuments, as did others, but people simply believed they were put there by others hikers, and added their own stones to the piles. I did the same. Never once did it occur to me that the piles of stones were monuments to something more important, something that I should have been respecting throughout my entire childhood.

Why does this matter to anyone?

In learning about one simple tradition, I gained a deeper understanding and respect for the culture, and it is something that I will spread to all those who I am with when I run into these monuments. I believe that it is important to take the time to learn about other cultures, and it is important to learn to respect them. Objects such as the first hand accounts regarding some old white man’s first experience with the Nez-Percés tribe, albeit biased, is something that we must study in order to understand past mistakes, and in order to never make them again. Maps of conquests, while violent, are something that we must view in order to understand the occurrences and events that formed the present. First hand accounts are something that we must listen to, and something that we must always respect, especially when they are difficult to share. While we cannot truly understand, we must make an effort in order to avoid the mistakes of our predecessors and ancestors. Through research, discussion, and open-mindedness to learn, we must work to understand and respect everyone.

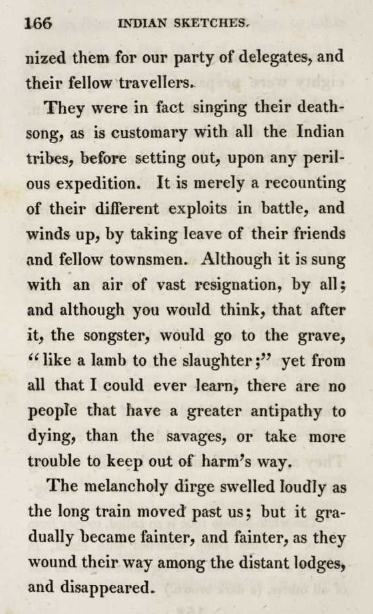

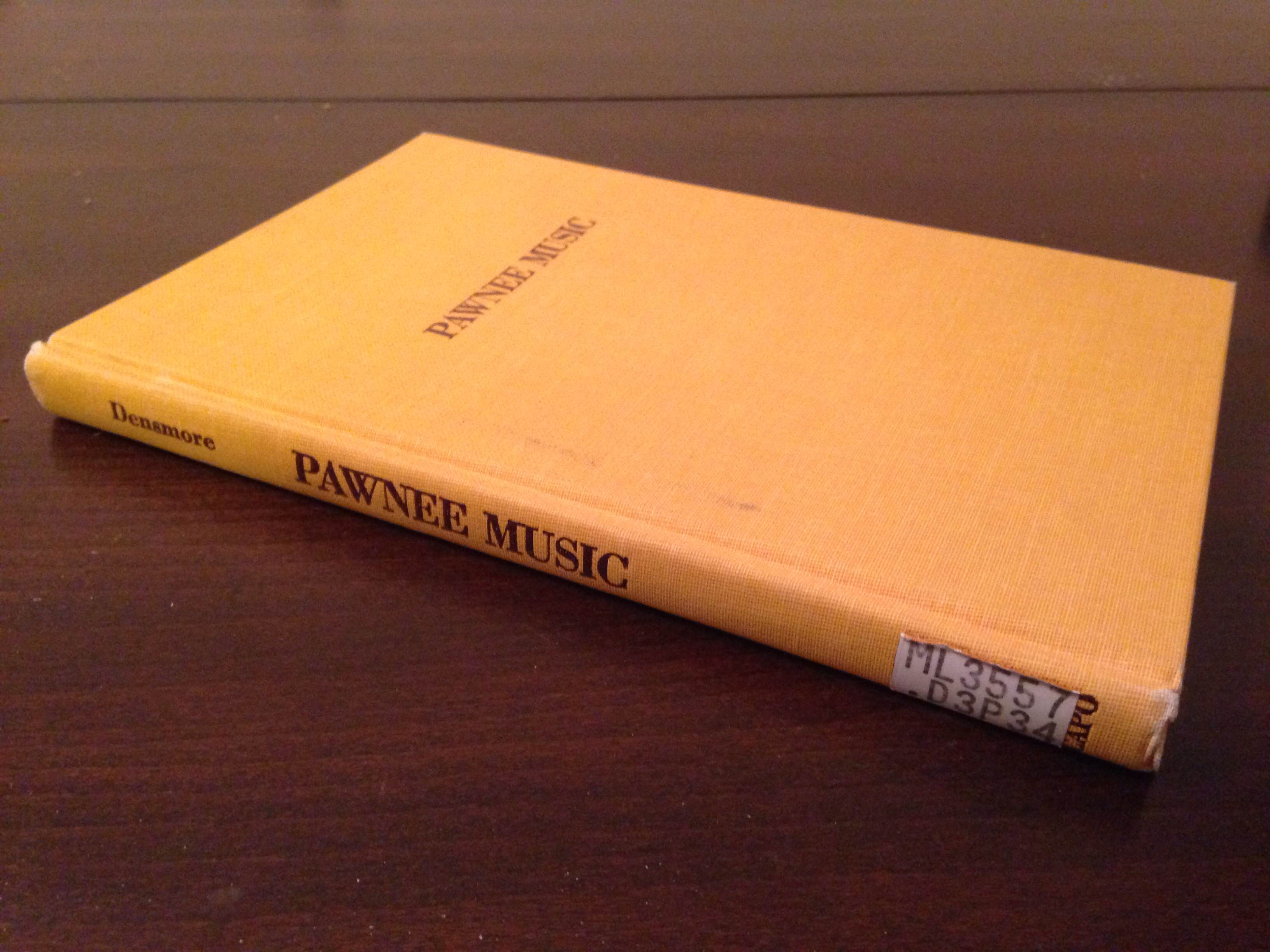

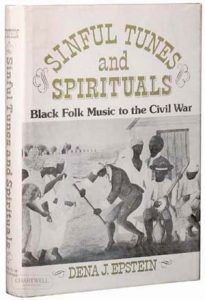

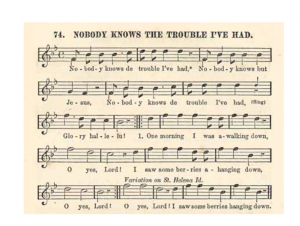

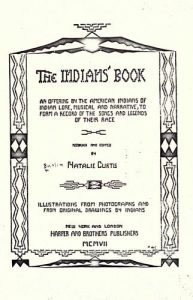

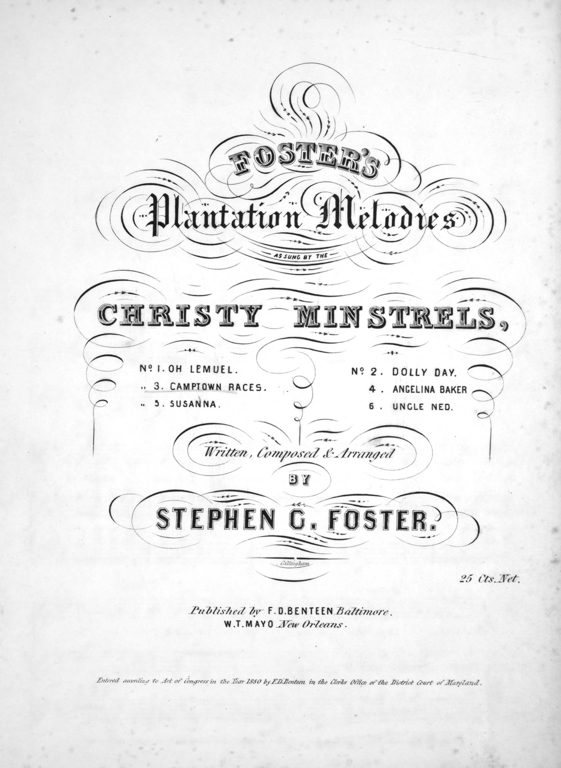

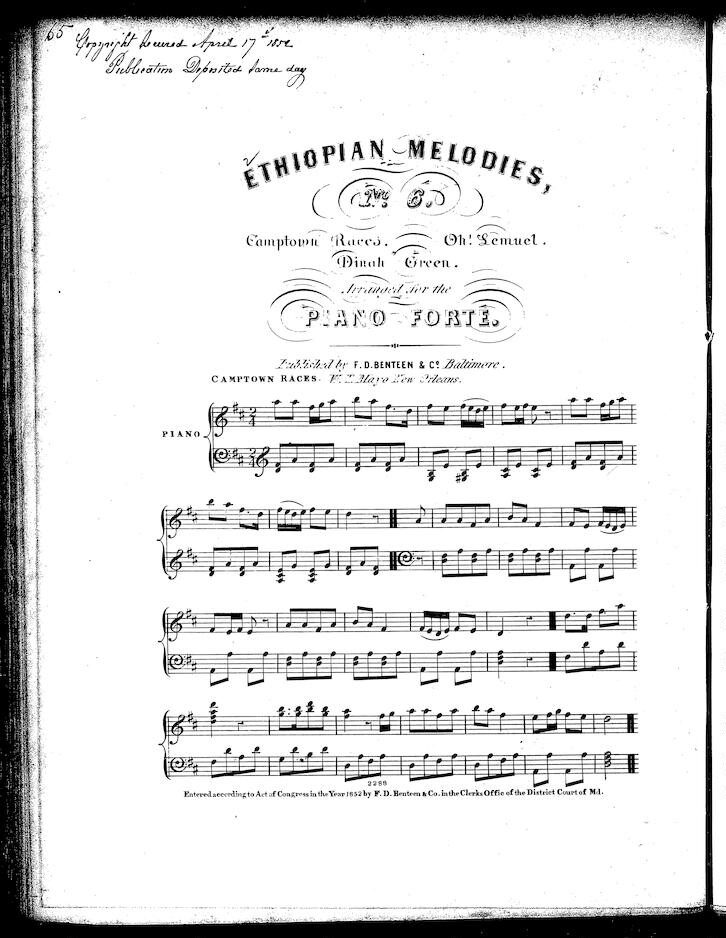

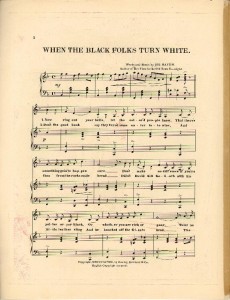

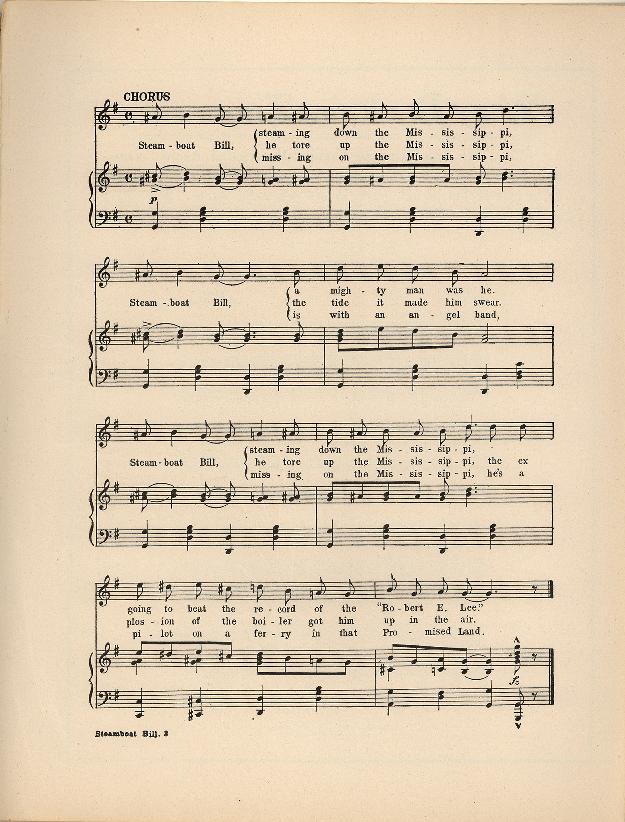

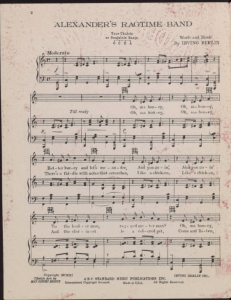

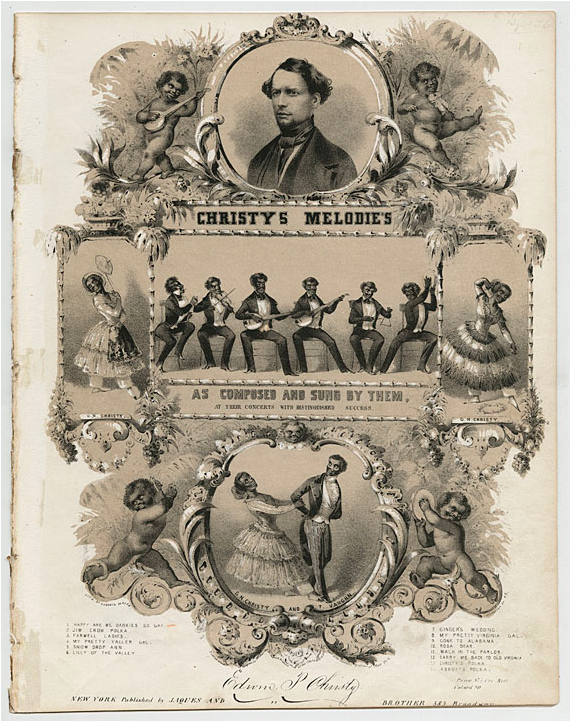

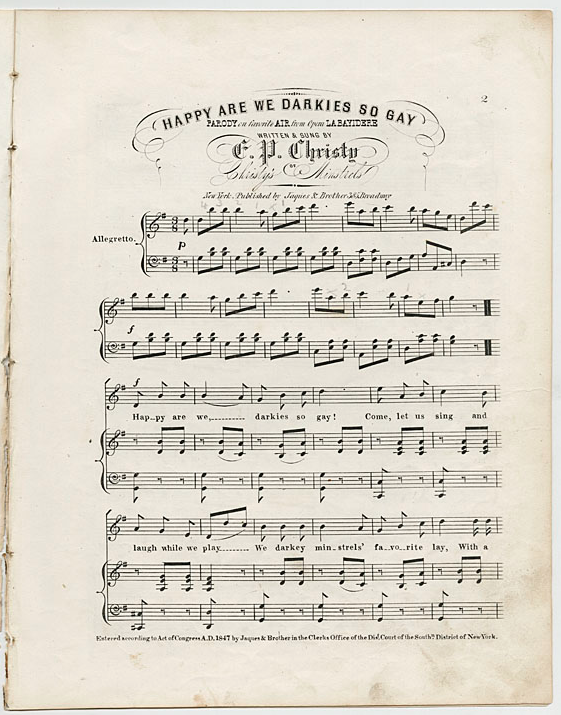

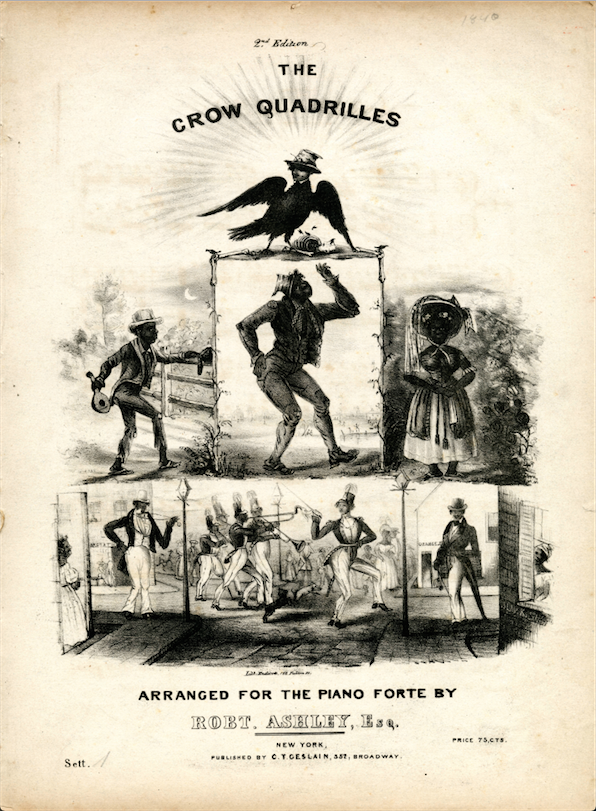

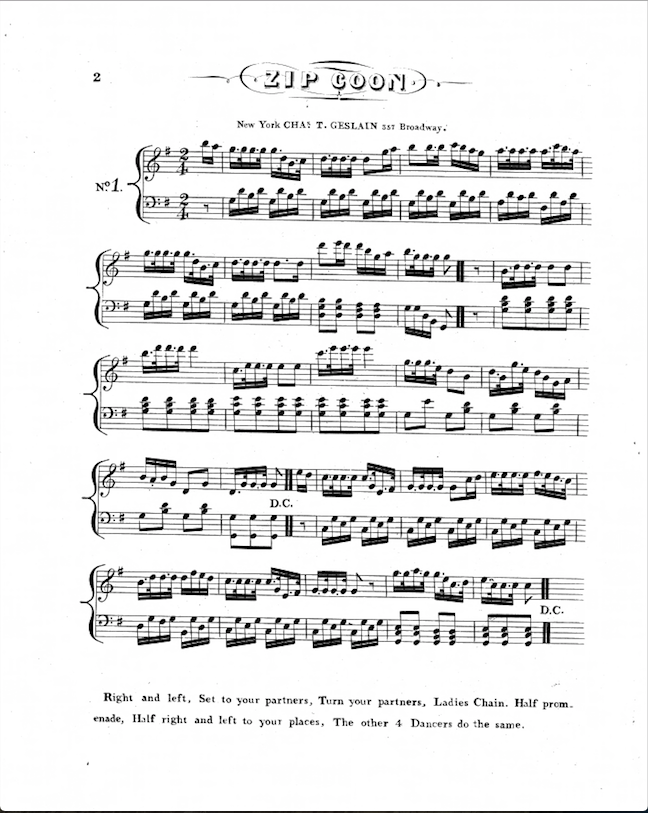

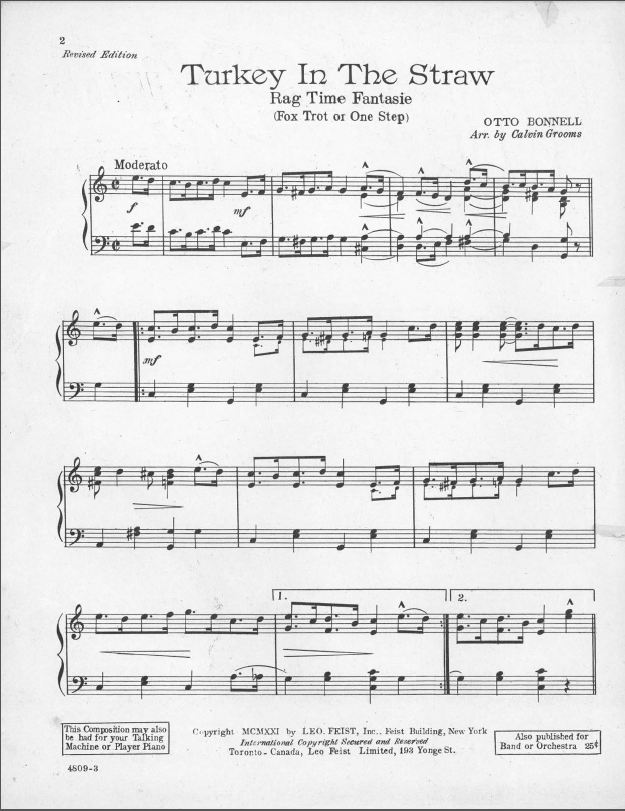

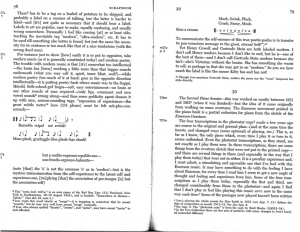

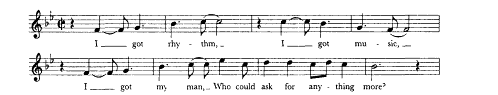

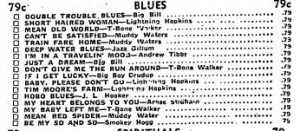

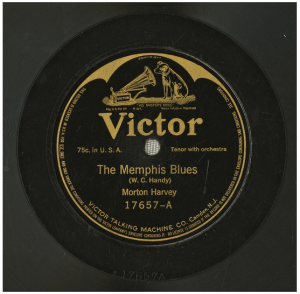

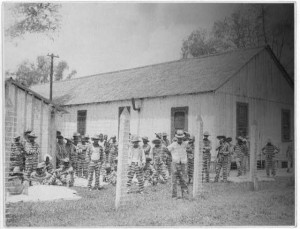

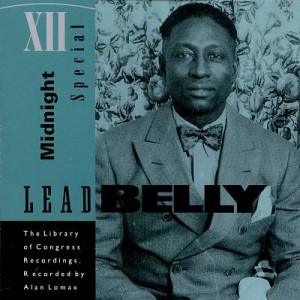

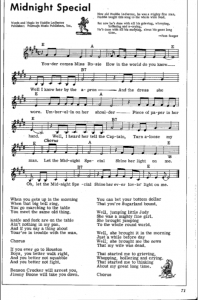

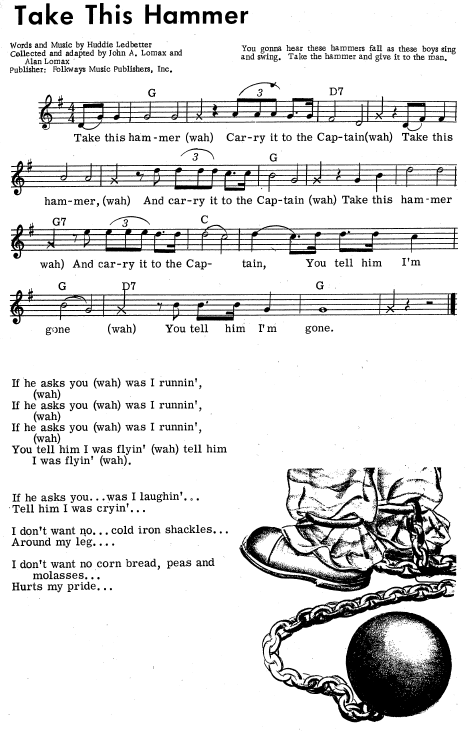

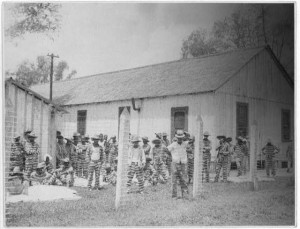

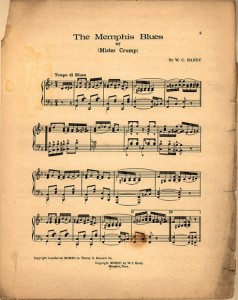

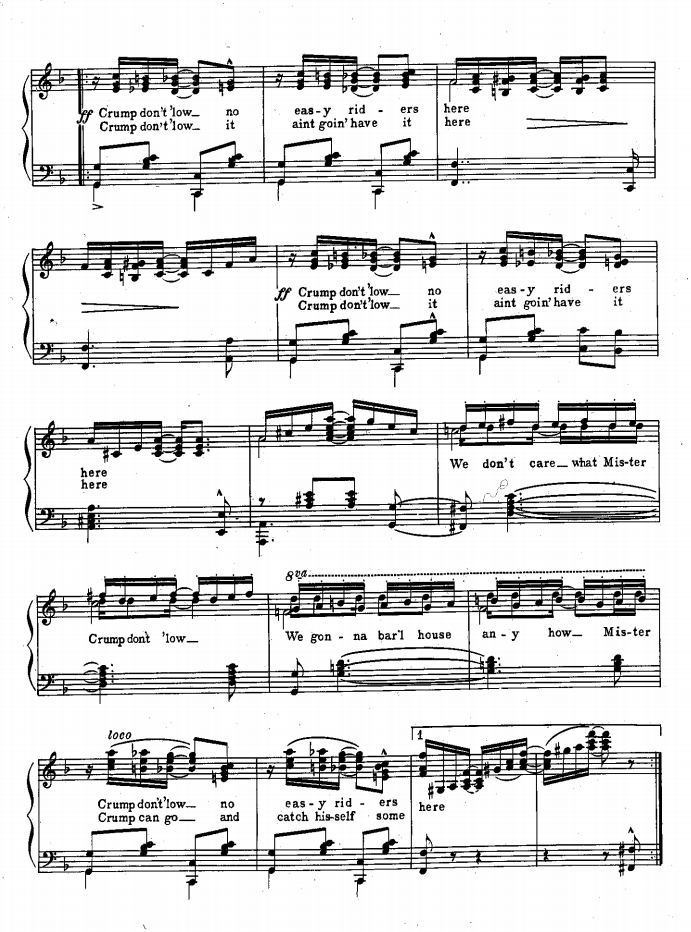

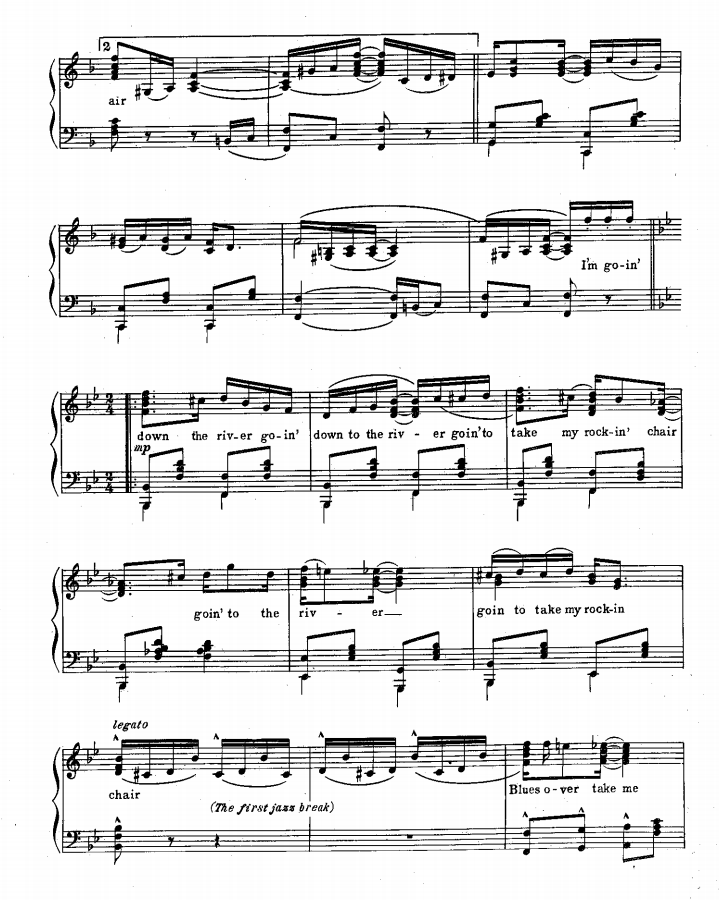

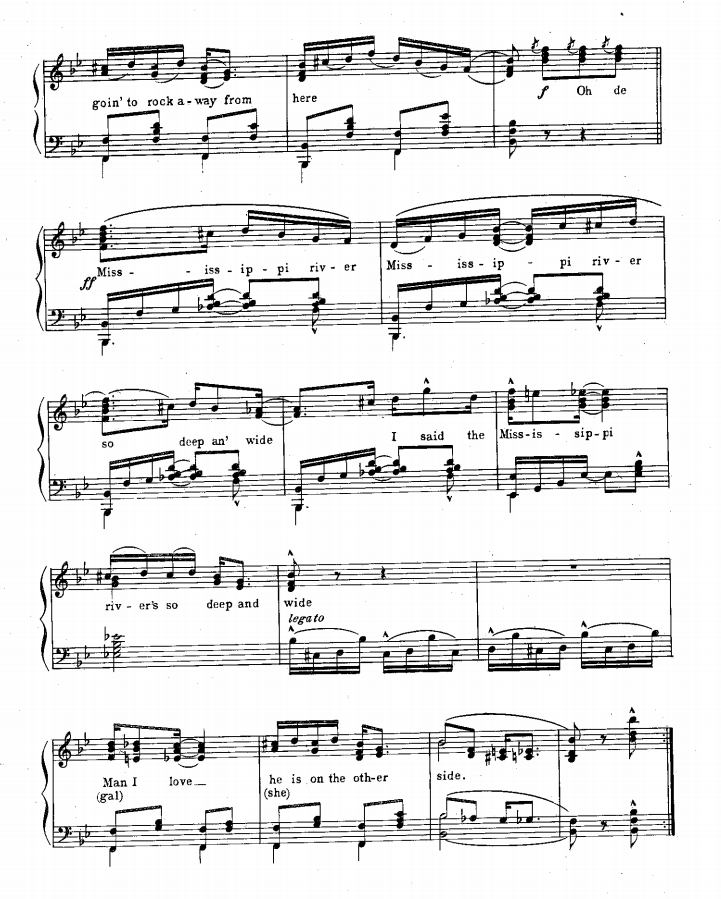

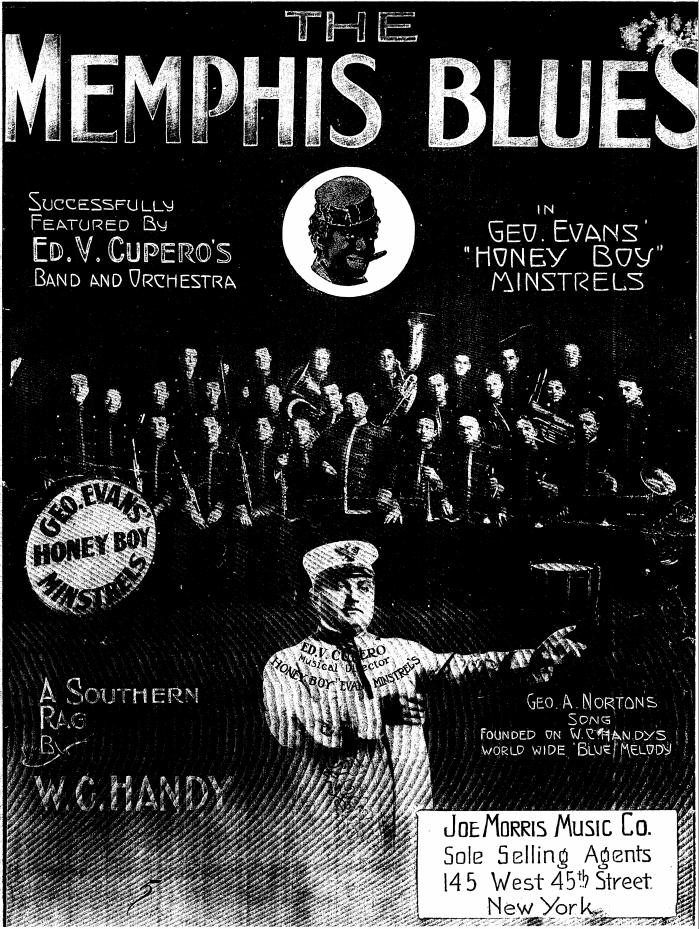

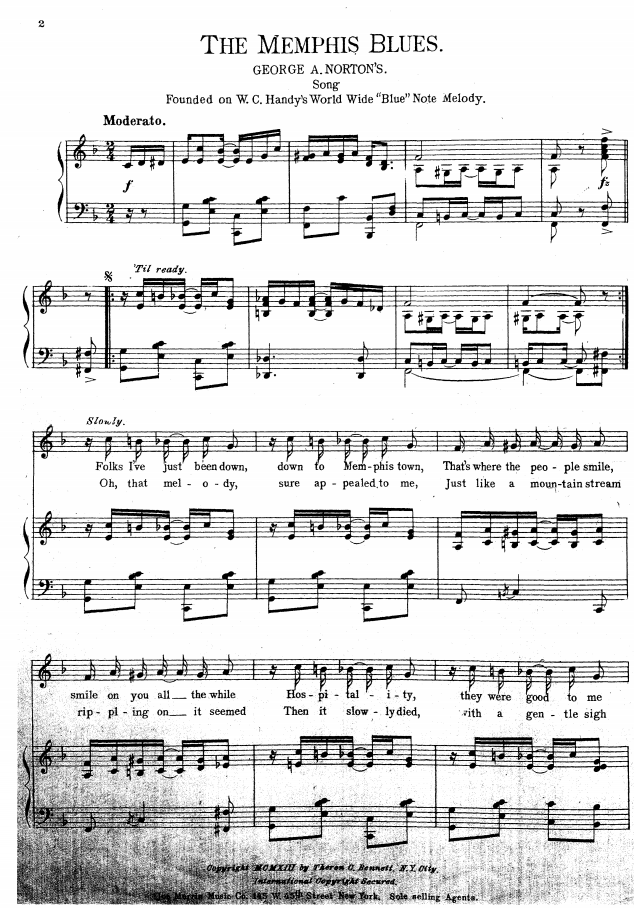

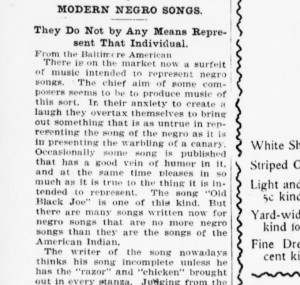

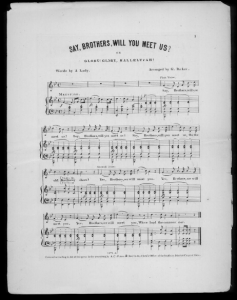

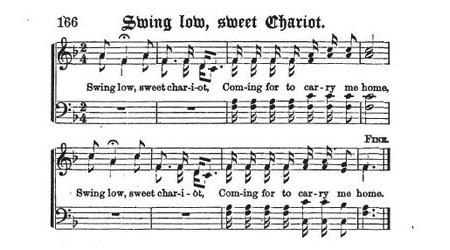

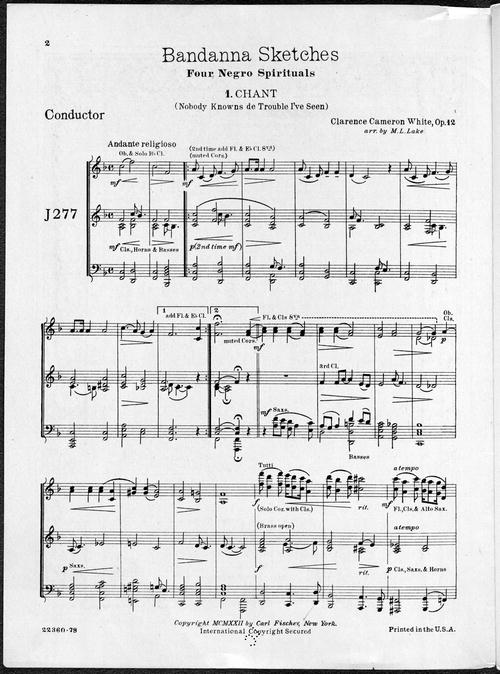

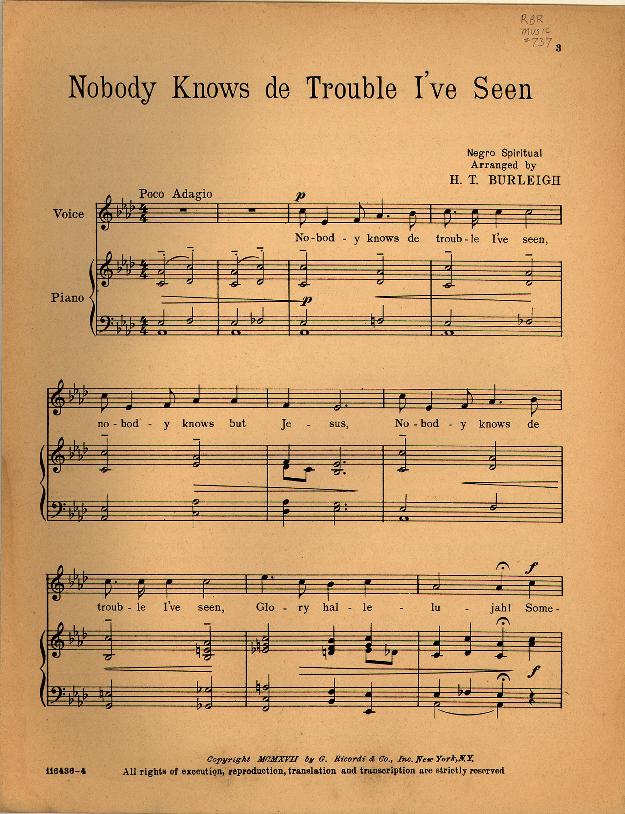

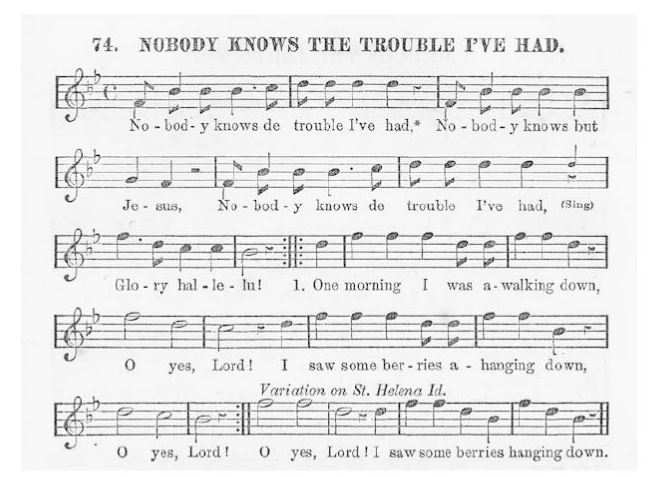

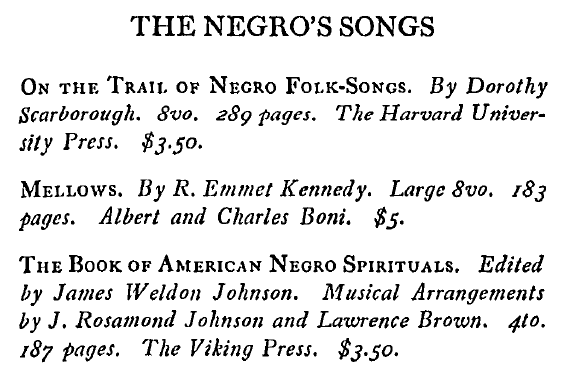

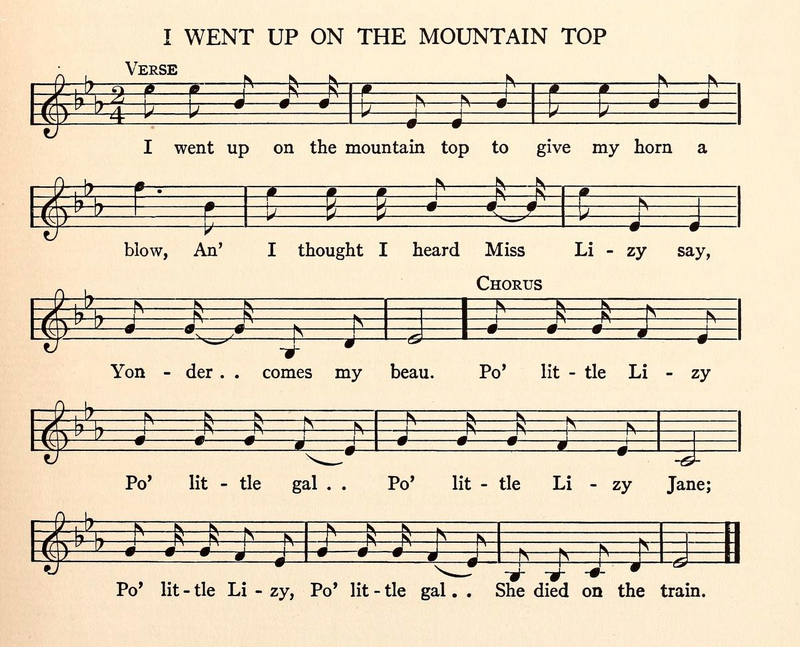

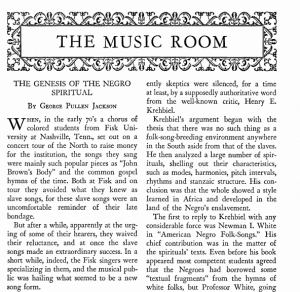

ns that black folk musicians established in their practice. These songs were all sung by slaves, mostly in the fields where they worked. Sometimes these songs were used to communicate messages, making use of metaphors or other poetic techniques that disguised their meanings to the slave owners that may have heard them, but to other slaves, the message would be clear. Through this kind of code, a sort of secretive communication started to develop. I believe that this book would make an excellent contribution to the museum exhibit because it provides high-quality scholarly insight into the history of black folk music and makes use of artifacts leftover from that time period where some of these songs were recorded in our standard western musical notation. This book also makes use of images to provide a supplemental visual aid to the reader to be able to picture the events and the parts of history that are described within it. Furthermore, there are tons of scores contained within the book, so if one wanted to attempt to recreate these songs in the present day, it would be possible to do so to some extent. Obviously, like we’ve mentioned in class, there are lots of stylistic performance techniques that are lost in the process of notating these songs, but having the notes at least preserves it in some sense as to not let it die out.

ns that black folk musicians established in their practice. These songs were all sung by slaves, mostly in the fields where they worked. Sometimes these songs were used to communicate messages, making use of metaphors or other poetic techniques that disguised their meanings to the slave owners that may have heard them, but to other slaves, the message would be clear. Through this kind of code, a sort of secretive communication started to develop. I believe that this book would make an excellent contribution to the museum exhibit because it provides high-quality scholarly insight into the history of black folk music and makes use of artifacts leftover from that time period where some of these songs were recorded in our standard western musical notation. This book also makes use of images to provide a supplemental visual aid to the reader to be able to picture the events and the parts of history that are described within it. Furthermore, there are tons of scores contained within the book, so if one wanted to attempt to recreate these songs in the present day, it would be possible to do so to some extent. Obviously, like we’ve mentioned in class, there are lots of stylistic performance techniques that are lost in the process of notating these songs, but having the notes at least preserves it in some sense as to not let it die out.

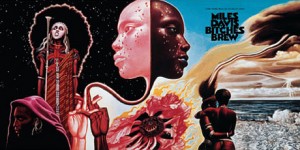

interesting challenge. Continuing the the trend of asking questions, what do these patterns mean? From what culture do they come from? How does it connect to American music?

interesting challenge. Continuing the the trend of asking questions, what do these patterns mean? From what culture do they come from? How does it connect to American music?

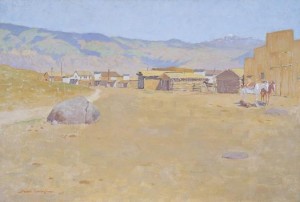

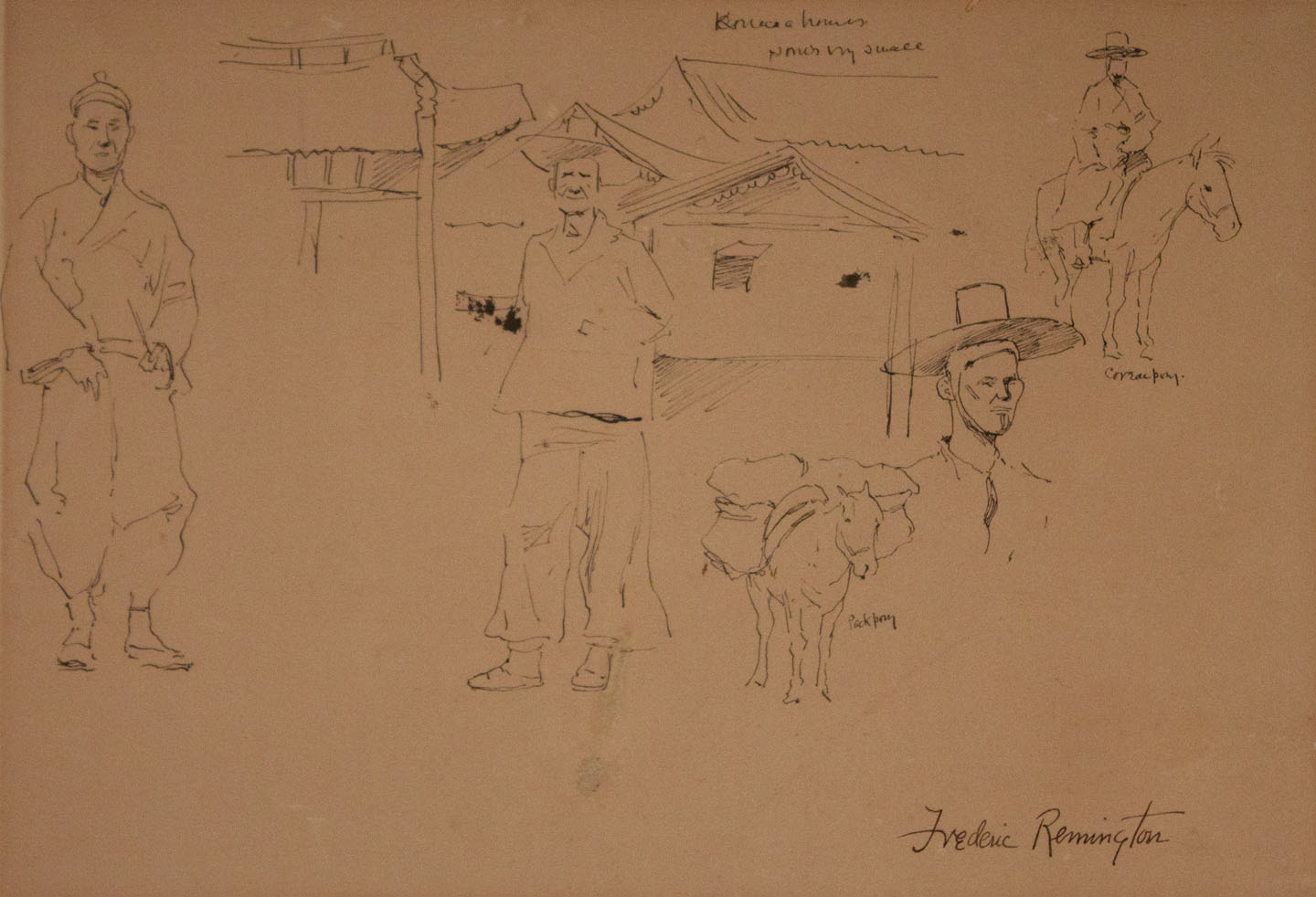

William Henry Jackson was tasked with exploring and surveying the American West at a time when America was expanding and the Manifest Destiny was still at the forefront of American ideology. Over his life of 99 years, Jackson became famous for his work with photochrom, such as the photo to the left from around 1900.[1] The branding of a calf is posed as a fairly leisurely activity, as a few of the characters stand around looking at their corral of cattle and the wide open space available to them in the West. Working for the government, Jackson often took exploration trips to photograph scenery along railroad routes and with his photography of beautiful natural landmarks, he even convinced Congress to create Yellowstone National Park. With photos like these, that show a decent life on the frontier and human’s domination over nature, Jackson’s narrow lens paints a Romantic image of the west, sure to keep out the fact that many Native Americans were displaced as a result.

William Henry Jackson was tasked with exploring and surveying the American West at a time when America was expanding and the Manifest Destiny was still at the forefront of American ideology. Over his life of 99 years, Jackson became famous for his work with photochrom, such as the photo to the left from around 1900.[1] The branding of a calf is posed as a fairly leisurely activity, as a few of the characters stand around looking at their corral of cattle and the wide open space available to them in the West. Working for the government, Jackson often took exploration trips to photograph scenery along railroad routes and with his photography of beautiful natural landmarks, he even convinced Congress to create Yellowstone National Park. With photos like these, that show a decent life on the frontier and human’s domination over nature, Jackson’s narrow lens paints a Romantic image of the west, sure to keep out the fact that many Native Americans were displaced as a result.

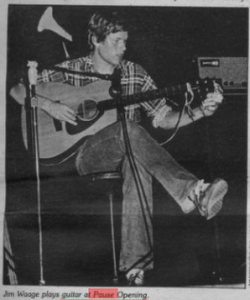

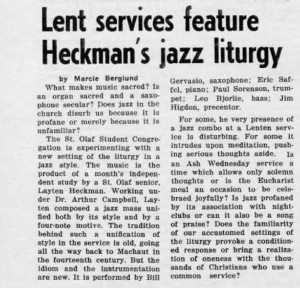

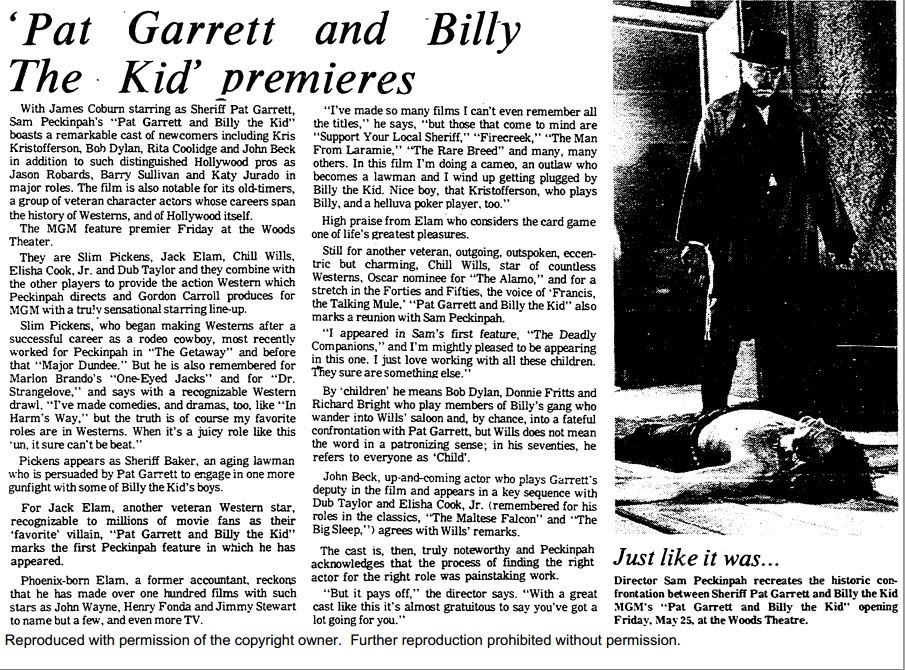

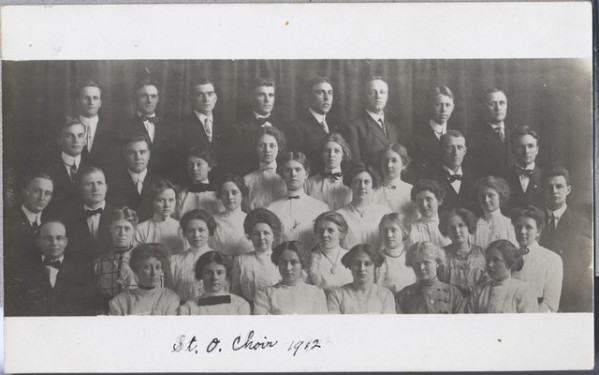

It seems St. Olaf has been hesitant to embrace Jazz as a sound musical genre, especially in regard to liturgical music. In this 1968 article of the Manitou Messenger, Ms. Berglund summarized a student jazz liturgy setting performed in chapel and asks questions that point to Jazz as a potentially profane and intrusive art form for worship. “Is jazz profaned by its association with night-clubs or can it also be a song of praise?”[1]

It seems St. Olaf has been hesitant to embrace Jazz as a sound musical genre, especially in regard to liturgical music. In this 1968 article of the Manitou Messenger, Ms. Berglund summarized a student jazz liturgy setting performed in chapel and asks questions that point to Jazz as a potentially profane and intrusive art form for worship. “Is jazz profaned by its association with night-clubs or can it also be a song of praise?”[1]

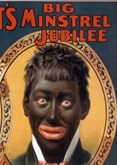

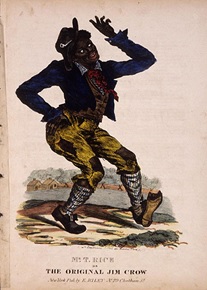

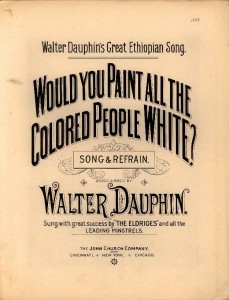

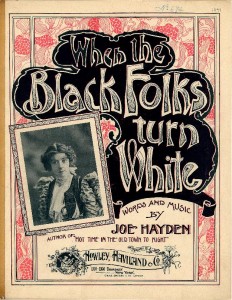

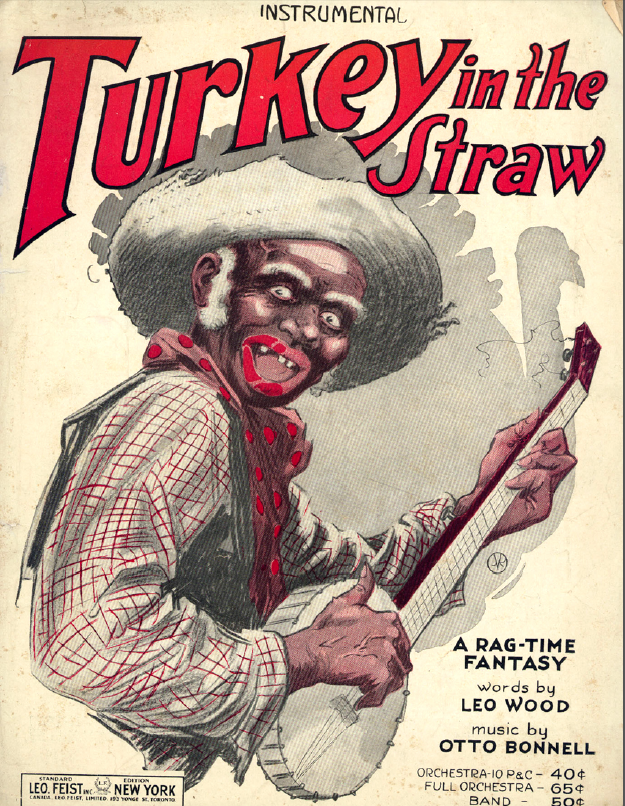

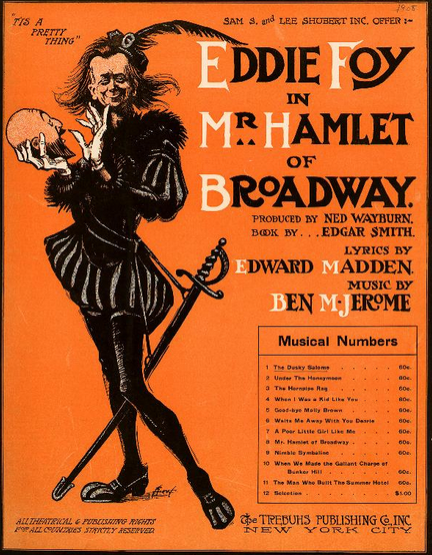

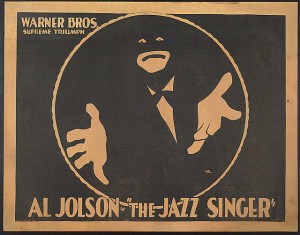

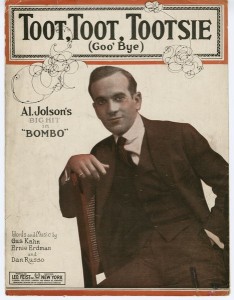

Much of the success of The Jazz Singer in 1927 is due to the massive popularity of the star Al Jolson. Regular concert goers and musical theater fans were familiar with Jolson who performed to sold-out audiences at the Winter Garden theater on Broadway. Jolson began performing in blackface make-up early in his career when he realized that it made him even more popular.

Much of the success of The Jazz Singer in 1927 is due to the massive popularity of the star Al Jolson. Regular concert goers and musical theater fans were familiar with Jolson who performed to sold-out audiences at the Winter Garden theater on Broadway. Jolson began performing in blackface make-up early in his career when he realized that it made him even more popular.

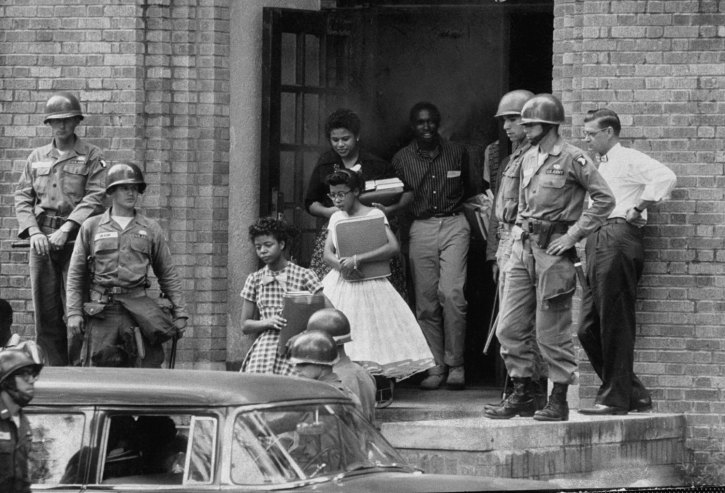

Armstrong was furious at the discrimination faced by the Little Rock Nine and did not hold back. In what was described as having the “explosive effect of an H-bomb”

Armstrong was furious at the discrimination faced by the Little Rock Nine and did not hold back. In what was described as having the “explosive effect of an H-bomb”

Ewing, Tom, ed. The Bill Monroe Reader. University of Illinois Press, 2000.

Ewing, Tom, ed. The Bill Monroe Reader. University of Illinois Press, 2000. Keil, Charles. “Who Needs” The Folk”?.” Journal of the Folklore Institute(1978): 263-265.

Keil, Charles. “Who Needs” The Folk”?.” Journal of the Folklore Institute(1978): 263-265.

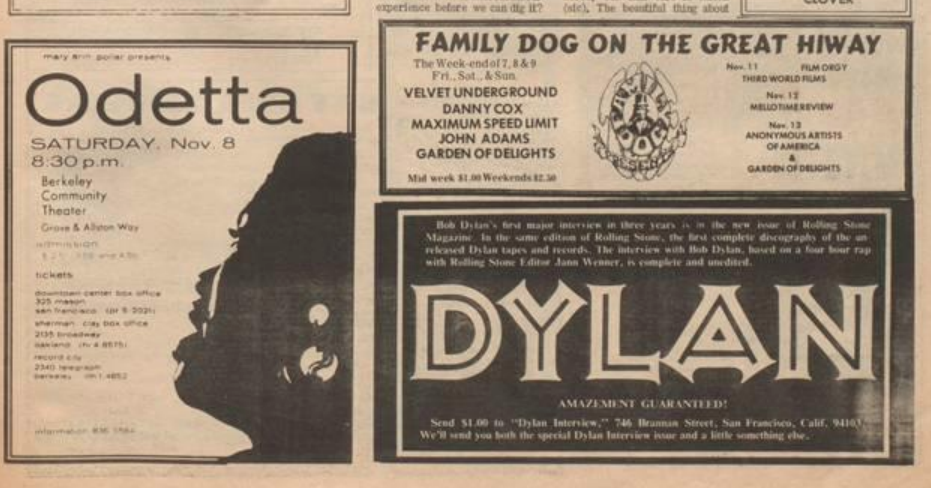

“Music concerts should be free,” he says. “Profit is pornography.” Rubin then gets himself kicked out of the festival by passing out “a copy of the free Yippie newspaper…(spiritual thoughts from our anarchist-revolutionary point of view)” to a pair of nuns. The magazines are deemed to have pornographic images themselves, and the festival cops escort Rubin out, Rubin blaming it on his hippie appearance.

“Music concerts should be free,” he says. “Profit is pornography.” Rubin then gets himself kicked out of the festival by passing out “a copy of the free Yippie newspaper…(spiritual thoughts from our anarchist-revolutionary point of view)” to a pair of nuns. The magazines are deemed to have pornographic images themselves, and the festival cops escort Rubin out, Rubin blaming it on his hippie appearance.

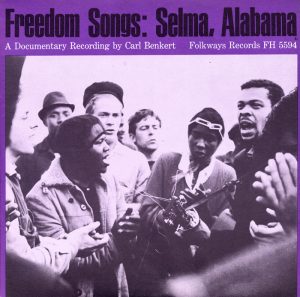

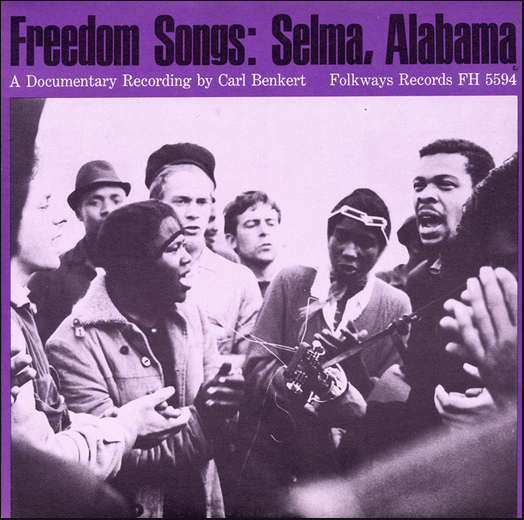

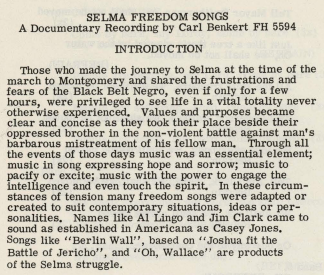

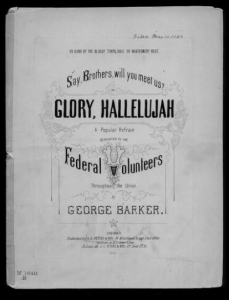

unique collection of recordings in their Smithsonian Folkways collection called “Freedom Songs: Selma, Alabama” which capture the emotional content of the march. Referred to as a “Documentary Recording,” Carl Benkert set out to preserve this moment in our nation’s history through sound. The liner notes confirm that “through all the events of those days, music was an essential element” and that the music expressed “hope and sorrow” while being able to “excite and pacify.”

unique collection of recordings in their Smithsonian Folkways collection called “Freedom Songs: Selma, Alabama” which capture the emotional content of the march. Referred to as a “Documentary Recording,” Carl Benkert set out to preserve this moment in our nation’s history through sound. The liner notes confirm that “through all the events of those days, music was an essential element” and that the music expressed “hope and sorrow” while being able to “excite and pacify.” article even specifically states that the police arrested “hymn-singing Negroes.”sup>

article even specifically states that the police arrested “hymn-singing Negroes.”sup>

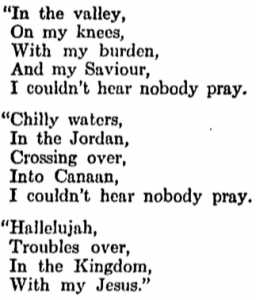

Figure 2

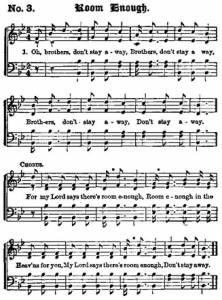

Figure 2 Figure 3

Figure 3

Oh, brothers, don’t stay away, . . .

Oh, brothers, don’t stay away, . . .

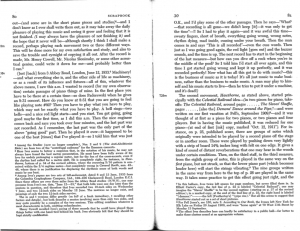

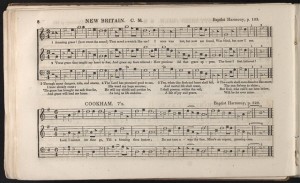

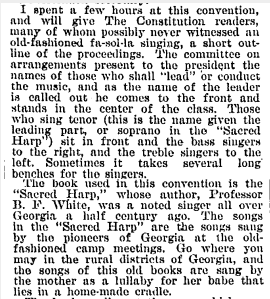

nging was mainly found in the Protestant sect of Christianity. Shape notes reinforce the importance of congregational style of singing in church, allowing for a broader inclusion of church-goers.

nging was mainly found in the Protestant sect of Christianity. Shape notes reinforce the importance of congregational style of singing in church, allowing for a broader inclusion of church-goers. The volume is composed of very beautiful melodies; and harmonies of almost unequalled richness… The tunes are admirably adapted to the effective expression of poetry, a circumstance upon which the happiest effect of Christian Psalmody depend.” A boasting review of a simple style of music, which goes to show the nature of music during this time period in America. Neither monophonic nor polyphonic, this unique style, which is heterophonic in texture, has a surprising sound that is unfamiliar, even to a trained ear. The more popular hymnody has a far more recognizable polyphonic texture that most trained and un-trained ears are accustomed to.

The volume is composed of very beautiful melodies; and harmonies of almost unequalled richness… The tunes are admirably adapted to the effective expression of poetry, a circumstance upon which the happiest effect of Christian Psalmody depend.” A boasting review of a simple style of music, which goes to show the nature of music during this time period in America. Neither monophonic nor polyphonic, this unique style, which is heterophonic in texture, has a surprising sound that is unfamiliar, even to a trained ear. The more popular hymnody has a far more recognizable polyphonic texture that most trained and un-trained ears are accustomed to.

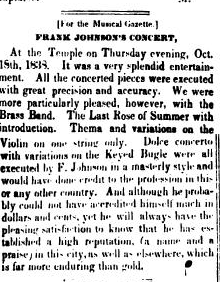

![[Francis Johnson.]](http://images.nypl.org/index.php?id=1257971&t=r)

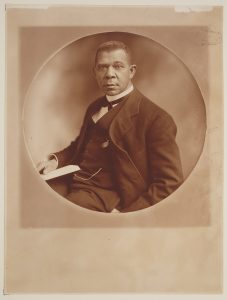

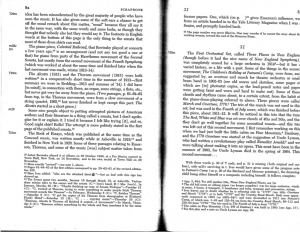

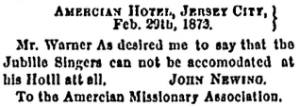

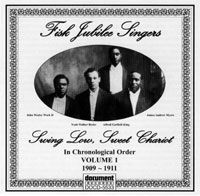

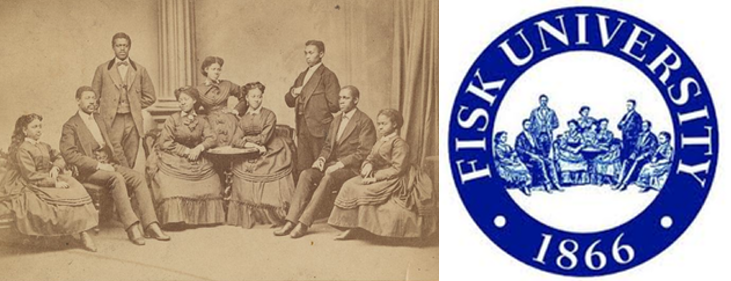

George L. White was originally hired to serve as Fisk’s treasurer, but also found his way into the music classroom. Noticing the institution’s need for income, the treasurer turned music professor also became the school’s first director of choirs. In 1871, White established a choir of freed slaves that he later named the Jubilee Singers. The choir’s purpose was to go and tour the country to raise money for the university. Ella Shepard, the ensemble’s pianist, described the intentions and drive of White was “to sing the money out of the hearts and pockets of the people,” and with that, on October 6, 1871, the choir left Nashville on their first benefit concert tour of the Midwest.

George L. White was originally hired to serve as Fisk’s treasurer, but also found his way into the music classroom. Noticing the institution’s need for income, the treasurer turned music professor also became the school’s first director of choirs. In 1871, White established a choir of freed slaves that he later named the Jubilee Singers. The choir’s purpose was to go and tour the country to raise money for the university. Ella Shepard, the ensemble’s pianist, described the intentions and drive of White was “to sing the money out of the hearts and pockets of the people,” and with that, on October 6, 1871, the choir left Nashville on their first benefit concert tour of the Midwest. able to return to Nashville with $20,000 to be put into the institution. With the profit of their first tour, Fisk University was able to build it’s first permanent campus building, which was named Jubilee Hall and still serves the university to this day. So what exactly did the Jubilee Singers do to make their tour so successful? Simply put, they sang what they knew and what the people wanted to hear.

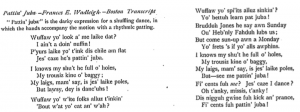

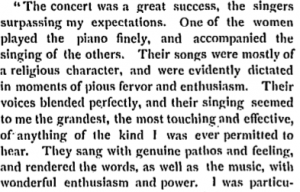

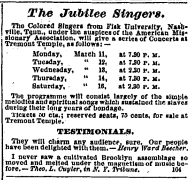

able to return to Nashville with $20,000 to be put into the institution. With the profit of their first tour, Fisk University was able to build it’s first permanent campus building, which was named Jubilee Hall and still serves the university to this day. So what exactly did the Jubilee Singers do to make their tour so successful? Simply put, they sang what they knew and what the people wanted to hear. are capable of singing ‘popular music’,” that had nothing to do with their success. What consistently worked for the ensemble was to defer to their “native, religious songs.” Described in one concert advertisement as the “simple melodies and spiritual songs which sustained the slaves during their long years of bondage,” the music of the Jubilee Singers captivated audiences with their novel sound and religious messages. When asked about their music by members of the public, the singers would respond that “it was never written down” and that is passed down “from generation to generation” within their families. This repertoire, coined “slave songs” would not only carry the ensemble through a successful tour, but also skyrocket them to the national and international stage.

are capable of singing ‘popular music’,” that had nothing to do with their success. What consistently worked for the ensemble was to defer to their “native, religious songs.” Described in one concert advertisement as the “simple melodies and spiritual songs which sustained the slaves during their long years of bondage,” the music of the Jubilee Singers captivated audiences with their novel sound and religious messages. When asked about their music by members of the public, the singers would respond that “it was never written down” and that is passed down “from generation to generation” within their families. This repertoire, coined “slave songs” would not only carry the ensemble through a successful tour, but also skyrocket them to the national and international stage.

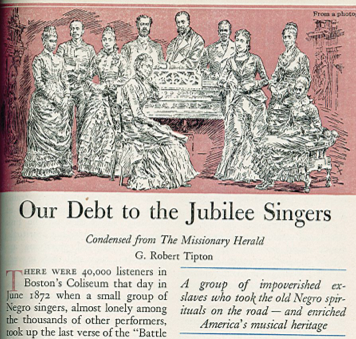

Regardless of your viewpoint on the ethics of choral repertoire when it comes to “selling” sound, the Fisk University Jubilee Singers have surely made their mark on our country’s history. More than 75 years after the Jubilee Singers inaugural tour, G. Robert Tipton wrote an article for The Missionary Herald in 1947, which was later re-published in Reader’s Digest in 1949, titled “Our Debt to the Jubilee Singers.” The article goes through a brief history of the ensemble from their establishment through their first European tour, but what I found most interesting was the summary sentence provided on the front page of the article. Tipton writes that the Jubilee Singers are “a group of impoverished ex-slaves who took the old Negro spirituals on the road – and enriched America’s musical heritage.” There is no doubt that the work of the Fisk University Jubilee Singers has not only enriched our nation’s musical antiquity, but quite possibly assisted in the preservation of the “slave song” genre that is so deeply rooted in America’s history.

Regardless of your viewpoint on the ethics of choral repertoire when it comes to “selling” sound, the Fisk University Jubilee Singers have surely made their mark on our country’s history. More than 75 years after the Jubilee Singers inaugural tour, G. Robert Tipton wrote an article for The Missionary Herald in 1947, which was later re-published in Reader’s Digest in 1949, titled “Our Debt to the Jubilee Singers.” The article goes through a brief history of the ensemble from their establishment through their first European tour, but what I found most interesting was the summary sentence provided on the front page of the article. Tipton writes that the Jubilee Singers are “a group of impoverished ex-slaves who took the old Negro spirituals on the road – and enriched America’s musical heritage.” There is no doubt that the work of the Fisk University Jubilee Singers has not only enriched our nation’s musical antiquity, but quite possibly assisted in the preservation of the “slave song” genre that is so deeply rooted in America’s history.