Frederic Remington (1861-1909) was an American painter, sculptor, illustrator, and writer (no relation to the rifle- and typewriter-makers, Eliphalet and Philo Remington). Although he studied for short periods at Yale’s School of Fine Arts as well as at the Art Students League in New York, he was a mostly self-taught artist. After a period traveling through the Dakotas, Montana, the Arizona Territory, and Texas, he had one of his drawings published in Harpers’s Weekly, leading to a long relationship with that publication as well as with The Century Illustrated and Scribner’s Magazine.

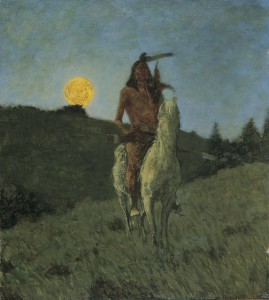

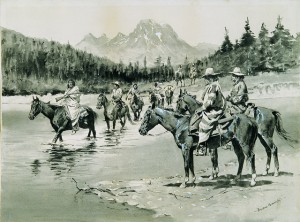

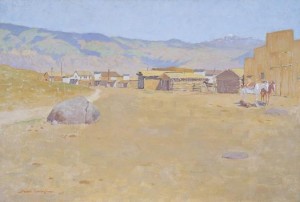

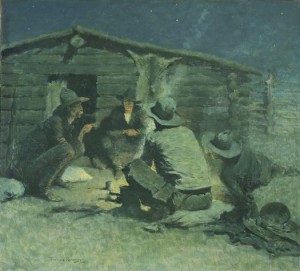

Due to Remington’s first-hand experience with the quickly-vanishing frontier, he grew renowned for his visual and textual depictions of cavalry, cowboys, Native Americans, and the American West:

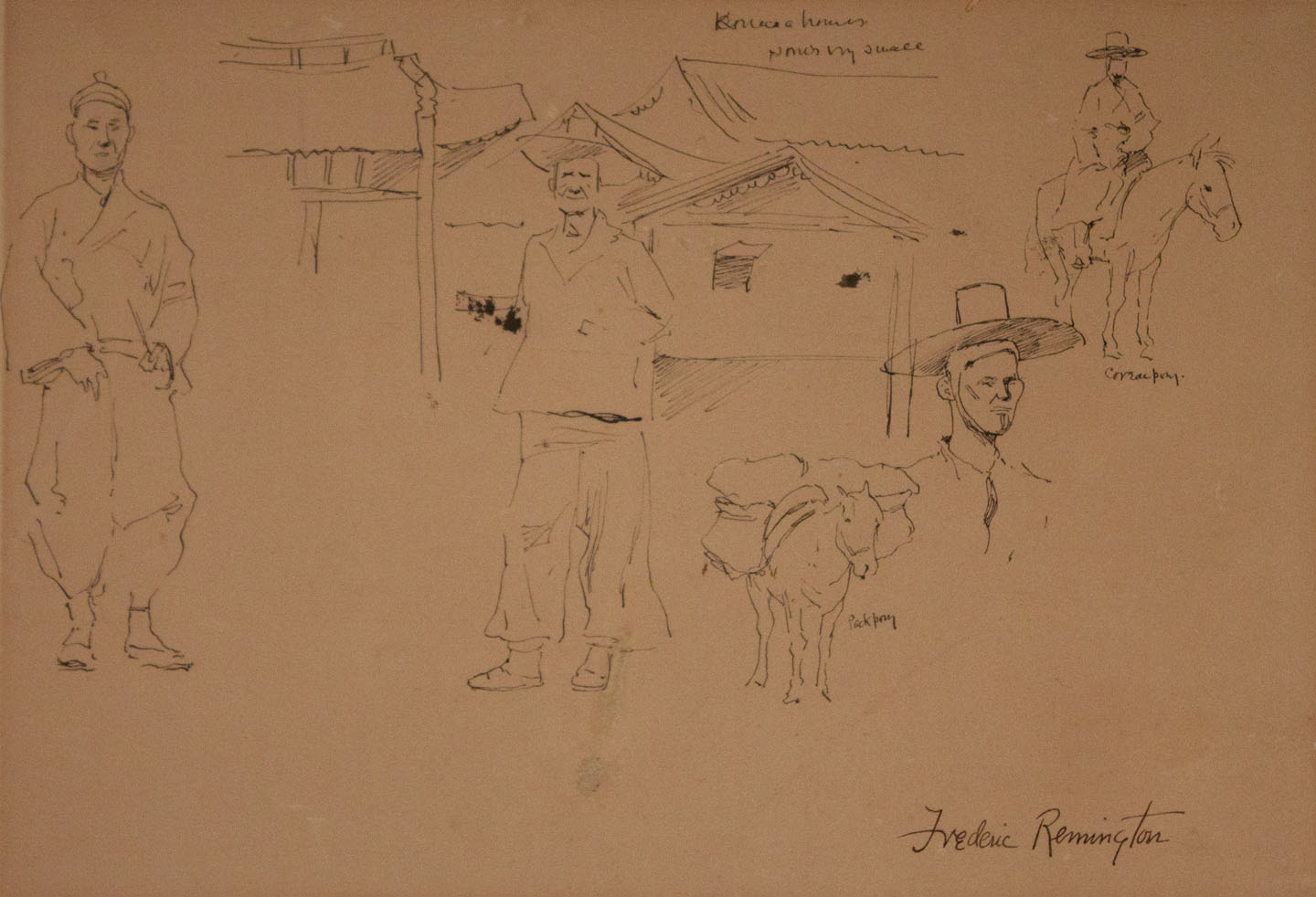

Knowing about his affinity for the American West, it might at first seem odd that while painting cowboys and campfires Remington also drew this Chinese figure study:

I promise you though, this is not odd at all.

As everyone knows, America is a land of immigrants, referred to in past years as the great melting pot (now we opt for the great salad bowl, kaleidoscope, or mosaic). Beginning in the 19th century, immigrants from China came to America, especially to the West, to work as laborers for the transcontinental railroad and the mining industry. These immigrants faced fierce racial discrimination, leading to such laws as the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act, prohibiting immigration from China for ten years, and the 1892 Geary Act, extending the prohibition for another decade. Thus the presence of Chinese immigrants in the American West would not have been uncommon, and Remington would have found many study subjects as he traveled the frontier.

“That’s interesting, but why is this post in a music history blog?”

By presenting a Chinese figure in various outfits, Remington demonstrates the Americanization of immigrants: on the left is a figure in more traditional clothing, while the figures on the right take on more and more aspects of Western culture, such as replacing the tunic with a baggy shirt and the cap with a Spanish guacho or grandee. So, by including Chinese immigrants in his oeuvre, Remington was portraying other cultures as an important piece of the American pie. In similar ways, composers like Amy Beach, Edward MacDowell, and Antonín Dvořák also sought to include other cultures as members of the American family.

Take the fifth movement of MacDowell’s Indian Suite of 1892, which pulls tunes from the Iroquois tribe:

Or listen to the Largo from Dvořák’s From the New World, which, while not directly copying songs, features original melodies similar to Native American music:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2TIFEQLANpw

Or sample Amy Beach’s Gaelic Symphony, in which she incorporates traditional Irish-Gaelic melodies, tapping into the rich heritage of a people long part of the American fabric:

Remington and these three composers are just a few of the numerous artists who rather than exoticizing other cultures sought to portray them as an essential part of the American melting pot.

Beach, Amy. Symphony in E-minor, No. 2 “Gaelic.” American Series Vol. 1. Detroit Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Neeme Järvi. Chandos CHAN 8958. Streaming audio. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VmLU1CfHcJw. Accessed April 29, 2015.

Dvořák, Antonín. Symphony No. 9 “From the New World”, Op. 95. Prague Festival Orchestra, conducted by Pavel Urbanek. LaserLight Digital 15824. Streaming audio. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2TIFEQLANpw. Accessed April 29, 2015.

. “Remington, Frederic.” Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. Oxford University Press. http://www.oxfordartonline.com/subscriber/article/grove/art/T071404. Accessed April 29, 2015.

MacDowell, Edward. Suite No. 2 “Indian”, Op. 48. Village Festival. Bohuslav Martinu Philharmonic, conducted by Charles Johnson. Albany Records TROY 224. Streaming audio. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=efDZ100iJMQ. Accessed April 29, 2015.

Remington, Frederic. “A Mining Town, Wyoming.” Oil on canvas. Ca. 1898. Frederic Remington Art Museum Collection. https://www.flickr.com/photos/fredericremington/6329189165/in/set-72157649247951734. Accessed April 29, 2015.

Remington, Frederic. “Chinese Figure Study.” Ink on paper. Date unknown. Flaten Art Museum Collection. http://embark.stolaf.edu/Obj4142?sid=162&x=83&sort=9. Accessed April 29, 2015.

Remington, Frederic. “Recent Uprising Among the Bannock Indians — a Hunting Party Fording the Snake River Southwest of the Three Tetons (Mountains).” Wash on paper. Ca. 1895. Frederic Remington Art Museum Collection. https://www.flickr.com/photos/fredericremington/5042171903/in/set-72157651574818071. Accessed April 29, 2015.

Remington, Frederic. “The Broncho Buster #275.” Bronze cast. 1895. Frederic Remington Art Museum Collection. https://www.flickr.com/photos/fredericremington/5169152407/in/set-72157625248734897. Accessed April 29, 2015.

Remington, Frederic. “The Outlier.” Oil on canvas. 1909. Frederic Remington Art Museum Collection. https://www.flickr.com/photos/fredericremington/5042214861/in/set-72157649247951734. Accessed April 29, 2015.

Remington, Frederic. “Then He Grunted and Left the Room.” Wash on paper. 1894. Frederic Remington Art Museum Collection. https://www.flickr.com/photos/fredericremington/6329996698/in/set-72157651574818071. Accessed April 29, 2015.

Remington, Frederic. Untitled [possibly The Cigarette]. Oil on canvas. Ca. 1908-1909. Frederic Remington Art Museum Collection. https://www.flickr.com/photos/fredericremington/6332165260/in/set-72157649247951734. Accessed April 29, 2015.